This blog explores how Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; rich in minerals, hydropower, forests, agriculture, and strategic trade corridors—remains Pakistan’s most overlooked economic goldmine. It uncovers the region’s vast yet underutilized potential, the governance gaps holding it back, and the reforms needed to transform KP into a powerful engine of national growth

INTRODUCTION

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa economy is one of Pakistan’s most paradoxical realities: a resource-rich region blessed by Allah SWT with extraordinary mineral wealth, immense hydropower capacity, abundant forests, fertile agricultural zones, and a strategic geo-economic position – yet it continues to lag far behind its true potential. Despite having resources that could transform Pakistan’s economic landscape, KP suffers from chronic underutilization due to conflict legacy, governance weaknesses, administrative turnover, outdated extraction systems, and low industrialization. Consequently, although KP has the building blocks of a high-income regional ecosystem, its slow economic conversion rate keeps growth stagnant.

Because KP contributes the majority of Pakistan’s crude oil, hosts more than 40 million tons of annual mineral extraction, and holds nearly half of the nation’s forests, the question naturally arises: why has this resource-rich region not risen economically? The answer lies not in scarcity, but in systems — or the lack of them. That is why understanding the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa economy requires a deep analysis of its geography, minerals, hydropower, agriculture, tourism, trade, governance, and reform pathways.

1. Geographic Foundations of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Economy

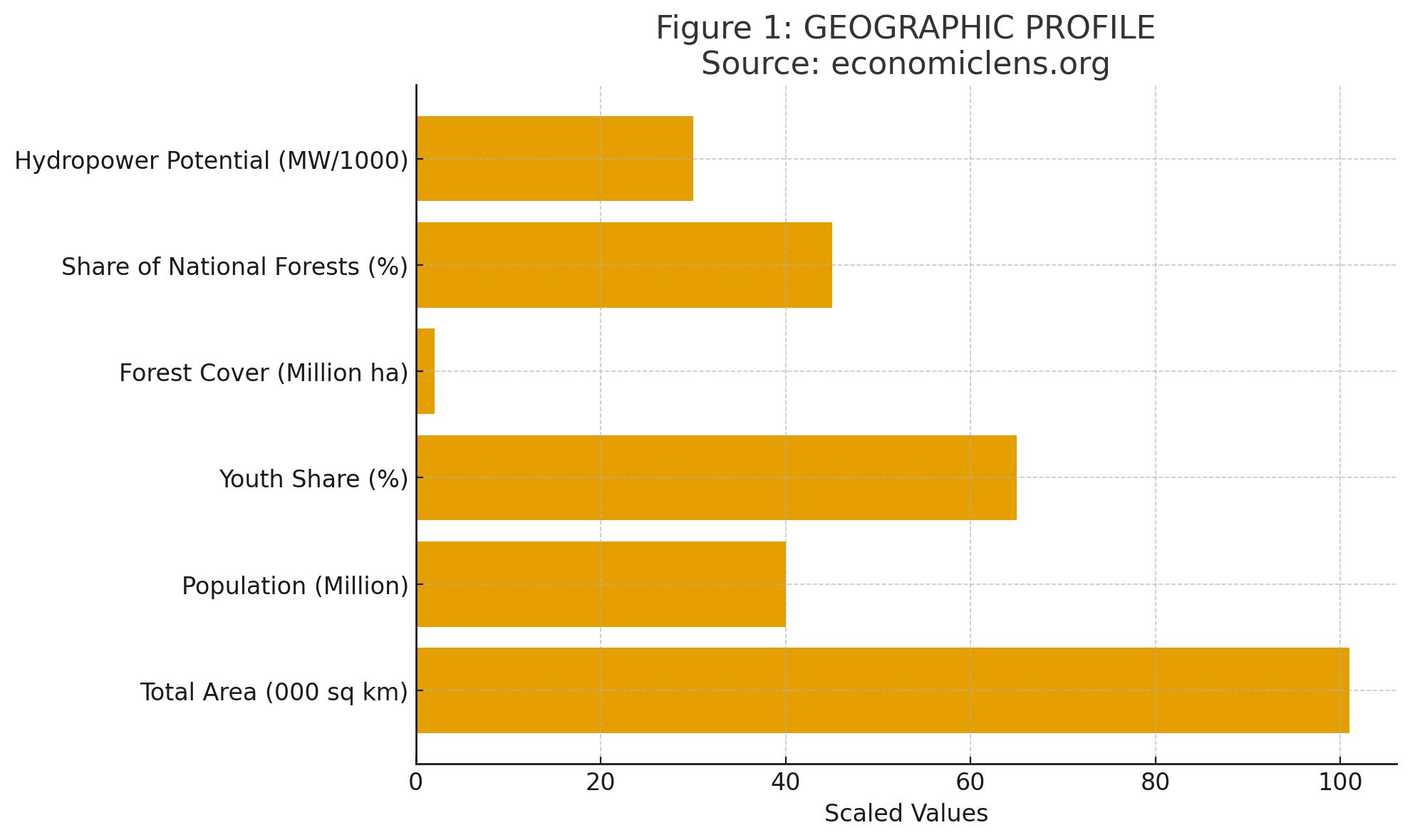

Geography is the first building block of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa economy, shaping everything from mining and tourism to hydropower and agriculture. The province combines snowcapped mountains, glacier-fed rivers, fertile plains, high-altitude forests, and dry southern zones — an ecological diversity extremely rare even globally. Because these terrains vary so dramatically, each region of KP has a distinct economic identity: the north for tourism and hydropower, the center for agriculture and services, and the south for minerals and trade. Furthermore, KP’s border with Afghanistan makes it Pakistan’s natural gateway to Central Asia, reinforcing its crucial role in regional transit.

Geographers emphasize that “KP possesses more economic geographies within a single province than many countries do in five,” highlighting how terrain shapes opportunity. UNDP assessments identify KP as Pakistan’s “hydrological core,” due to the river systems originating from its northern zones. Meanwhile, ADB’s connectivity reports classify Khyber Pass and Torkham as “strategic corridors capable of reshaping regional commerce.” Forestry and hydropower departments repeatedly underscore KP’s dominance: nearly half of Pakistan’s forests and half of its hydel potential lie here. Development economists further argue that KP’s ecological balance makes it uniquely suited for green energy, eco-tourism, and climate-resilient agriculture. Consequently, geography is not just land — it is KP’s economic architecture.

The data confirms that KP’s geography offers unparalleled economic leverage. Its forests, rivers, mountains, and transit corridors collectively form a natural economic engine capable of driving industrial, agricultural, and service-sector growth — if harnessed effectively.

“KP’s geography has already drawn the map of prosperity — all that remains is leadership that knows how to follow it.”

2. Minerals & Mining in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Economy

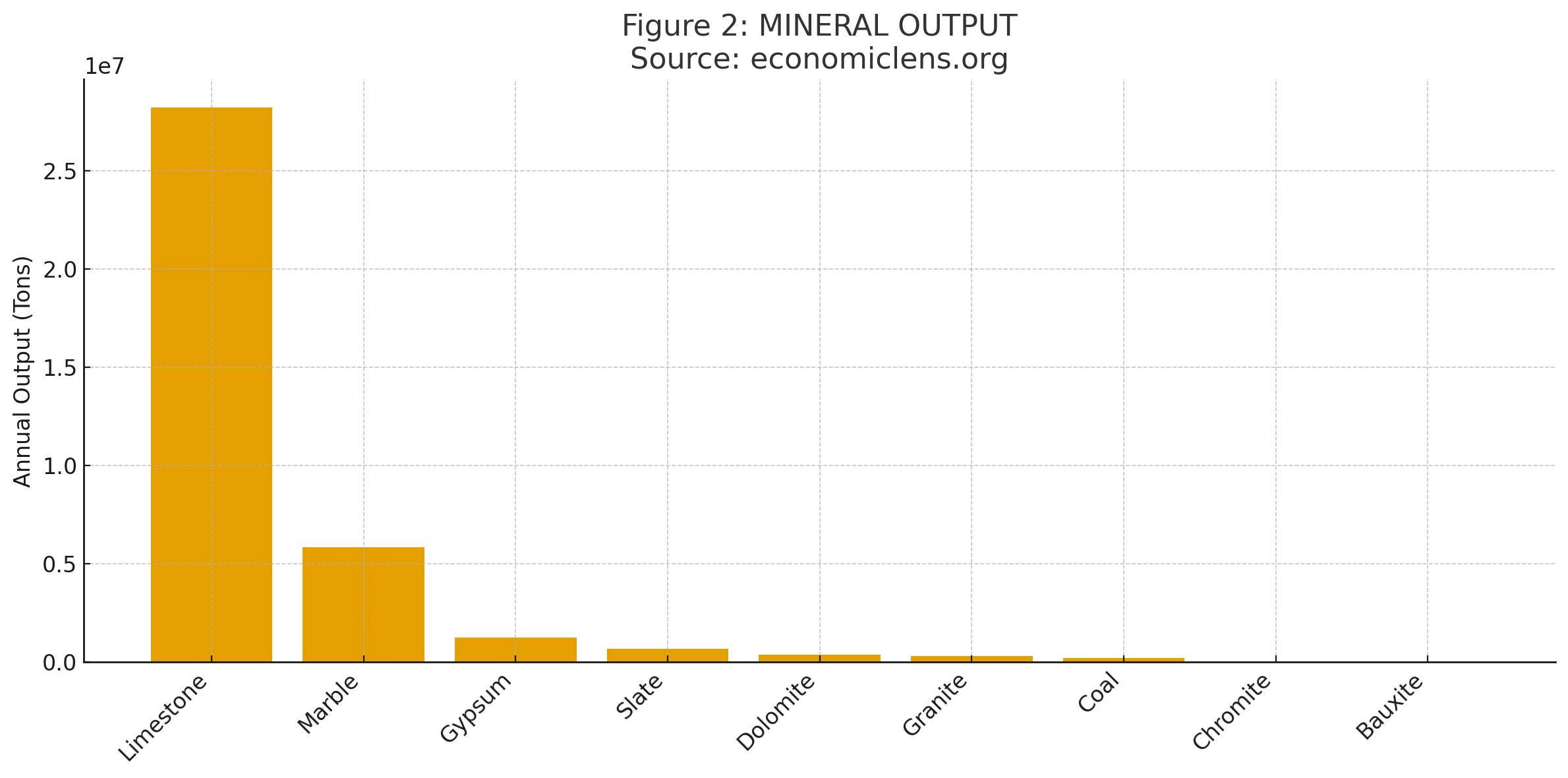

Mining is the central pillar of the resource-rich region, generating livelihoods across Buner, Mohmand, Khyber, Mansehra, Chitral, Orakzai, and Karak. KP hosts Pakistan’s richest deposits of marble, granite, limestone, chromite, dolomite, gypsum, slate, soapstone, fire clay, and coal. However, despite the enormous volume of extraction, KP’s mining sector remains trapped in low-value activity because 90% of minerals are exported raw — without cutting, polishing, grading, or treatment. Therefore, while KP extracts minerals, it does not create mineral wealth.

Mining specialists argue that KP’s dimension-stone belts are “world class,” yet outdated blasting destroys valuable stone and results in 75–85% wastage. Economic analysts highlight a major structural flaw: marble that could sell for $30–$50 per sq ft internationally is exported as raw blocks at $2–$4 per sq ft. Similarly, limestone and dolomite that could support ceramic, chemical, and construction industries are exported without processing. Reports from the Mines & Minerals Department confirm:

- 28 million tons of limestone

- 5.8 million tons of marble

- 1.2 million tons of gypsum

- 22,000+ tons of chromite

Yet value-addition plants, quality labs, and industrial clusters remain missing. Experts conclude that the KP mineral economy suffers not from a shortage of resources, but from a shortage of transformation.

The extraction volume shows enormous promise, but also exposes the core weakness of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa economy: KP extracts value, but exports wealth. Minerals can triple in value with local processing, but inadequate machinery, skill gaps, poor governance, and informal operators continue to keep KP stuck in the low-income zone.

“KP doesn’t need new minerals — it needs new methods. When extraction becomes industrialization, KP’s economy will rise faster than its mountains.”

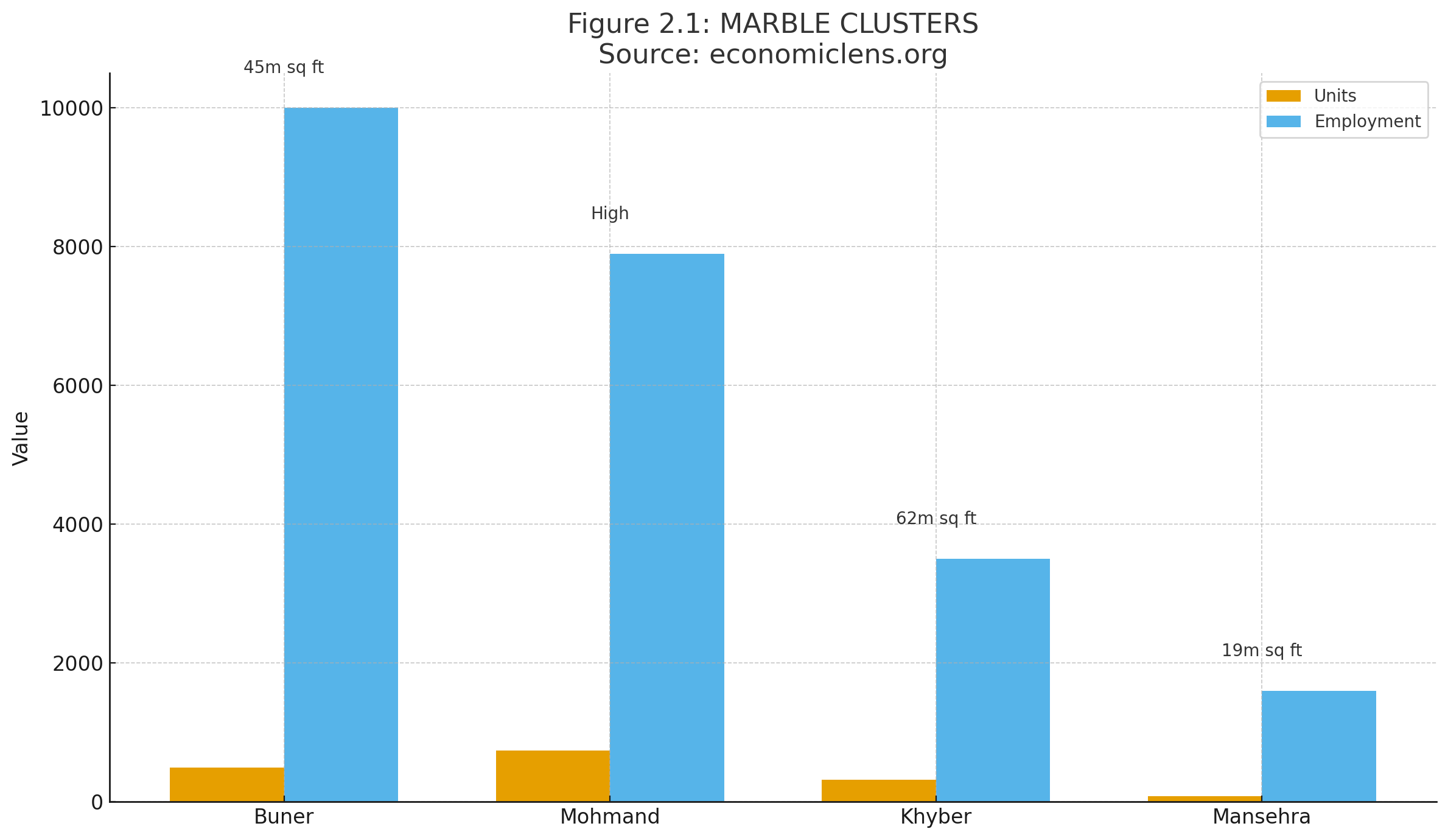

2.1 Marble & Dimension-Stone Strength of the Resource-Rich Region

Marble is KP’s signature mineral, shaping business ecosystems and livelihoods for decades. Buner, Mohmand, Khyber, and Mansehra host some of Asia’s most economically valuable marble veins — exporting hundreds of millions of square feet annually.

Stone experts describe KP’s marble belts as “one of the most commercially promising assets in South Asia,” yet emphasize that mechanization is almost nonexistent. International markets demand wire-cut blocks; KP exports blasted blocks. Reports show that wastage rates exceed 80% in some quarries, even though modern mechanization could reduce losses to 20%. Additionally, KP lacks polishing factories, industrial-scale cutters, grading centers, export facilitation hubs, and design labs.

Clusters are large and productive — but technologically outdated. With modernization, marble alone could become a multi-billion-dollar industry and a major export brand.

“Marble gave KP identity — modernization will give it prosperity. The stone is ready; KP must rise to shape it.”

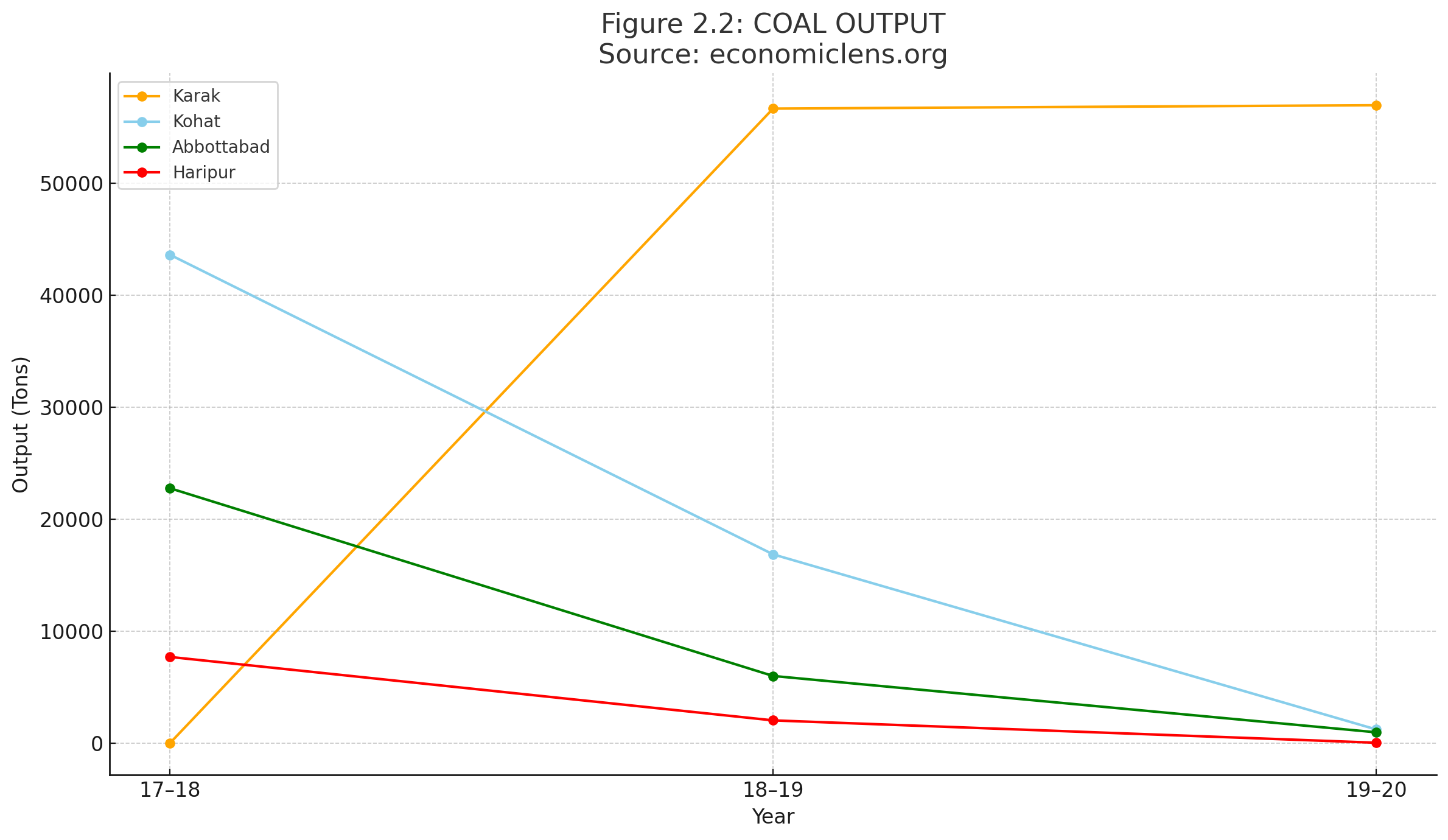

2.2 Coal in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Economy

Coal once formed a major part of the KP resource economy, especially in Karak, Hangu, Kohat, Orakzai, and Abbottabad. However, extraction is declining rapidly.

Energy experts attribute decline to unsafe mines, narrow seams, poor ventilation, collapsing tunnels, and weak regulation. Output in major districts has fallen by 90% in a decade.

Coal is no longer an economic driver. However, improved governance and consolidation could stabilize what remains.

“Coal may be fading — but safety, reform, and science can still save what’s left.”

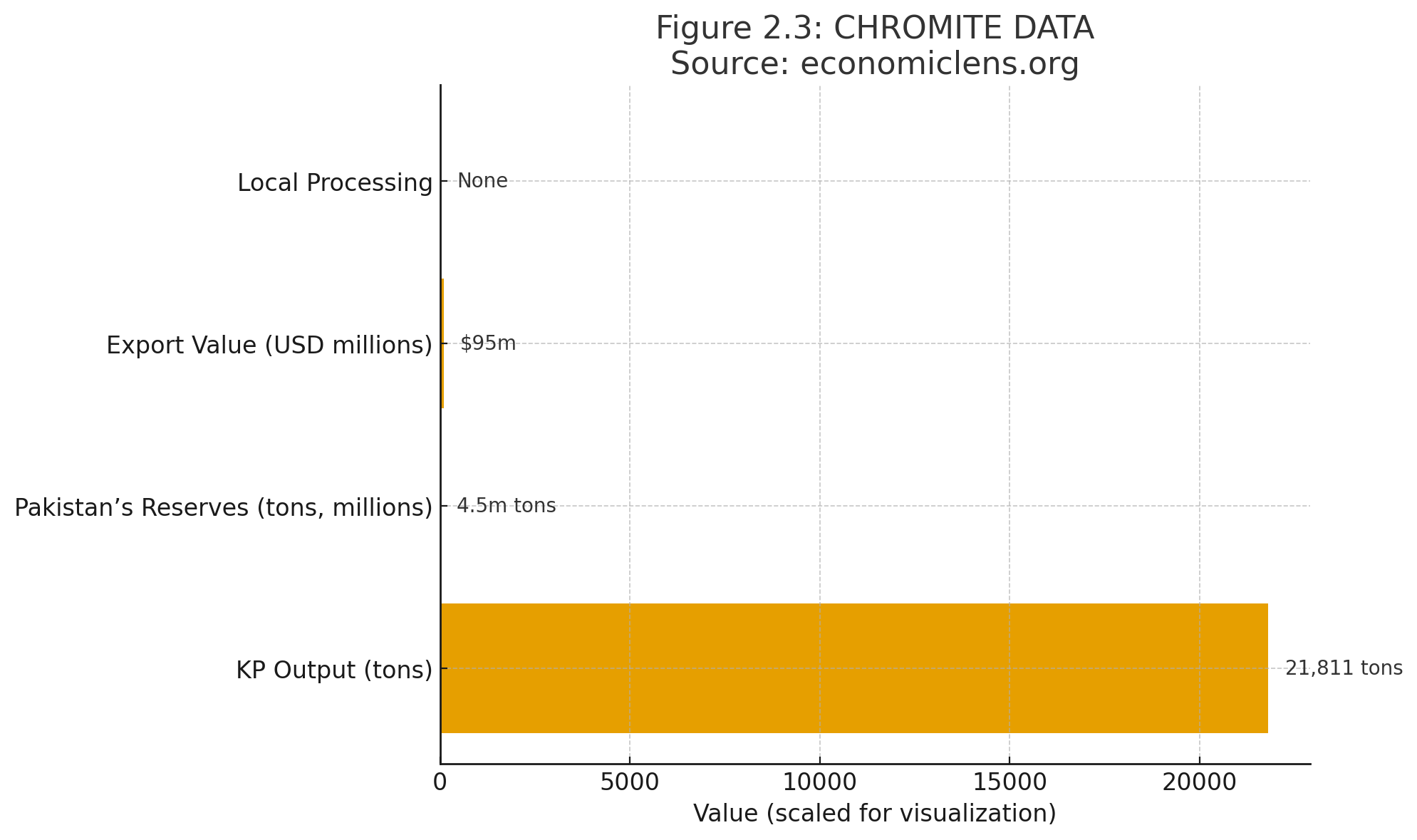

2.3. Chromite: KP’s Most Undervalued Mineral

Chromite is indispensable for stainless steel production. KP produces some of Pakistan’s highest-grade ore. Despite global demand, KP has no ferrochrome plants. Raw exports lose 70–80% of value.

Chromite is one of KP’s highest value-add opportunities — but remains untouched.

“The world needs stainless steel — KP has the metal. The question is: will KP process it, or just sell it raw forever?”

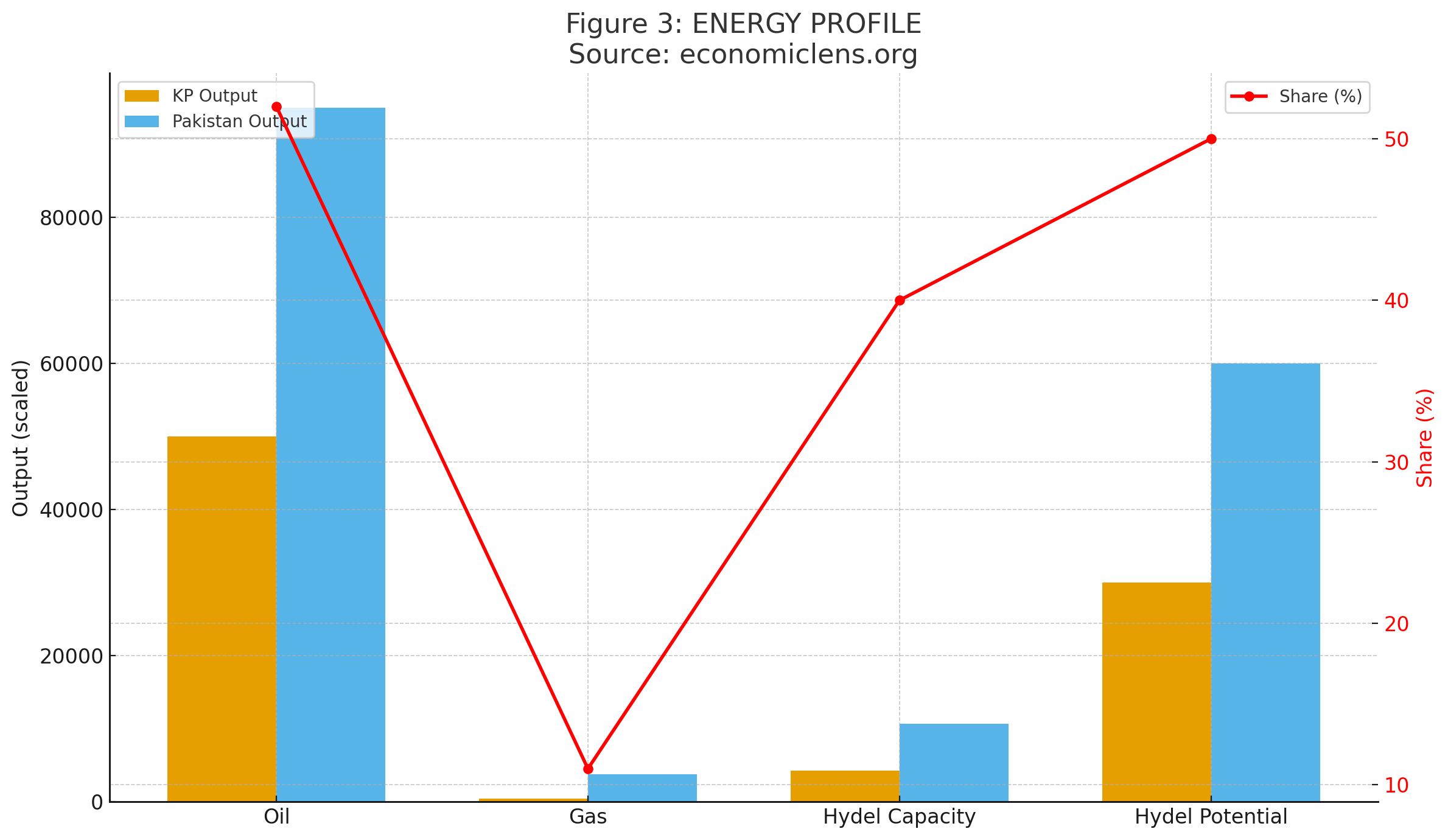

3. Energy & Hydropower Potential in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Economy

KP is Pakistan’s largest producer of crude oil, hosts major gas fields, and holds half of Pakistan’s hydropower potential. Energy is therefore not just a sector — it is KP’s future growth engine.

Hydropower experts confirm that KP alone can produce over 30,000 MW, enough to electrify half the country. PEDO notes delays due to federal approvals. KPOGCL reports that KP produces over 50% of national crude oil. Energy economists argue that with strategic investment, KP could become a net energy exporter to Pakistan.

Hydropower is KP’s fastest path to economic transformation. Oil and gas ensure fiscal stability. Together, they form a powerful economic backbone.

“Energy is power — literally. And KP has more of it than any other province.”

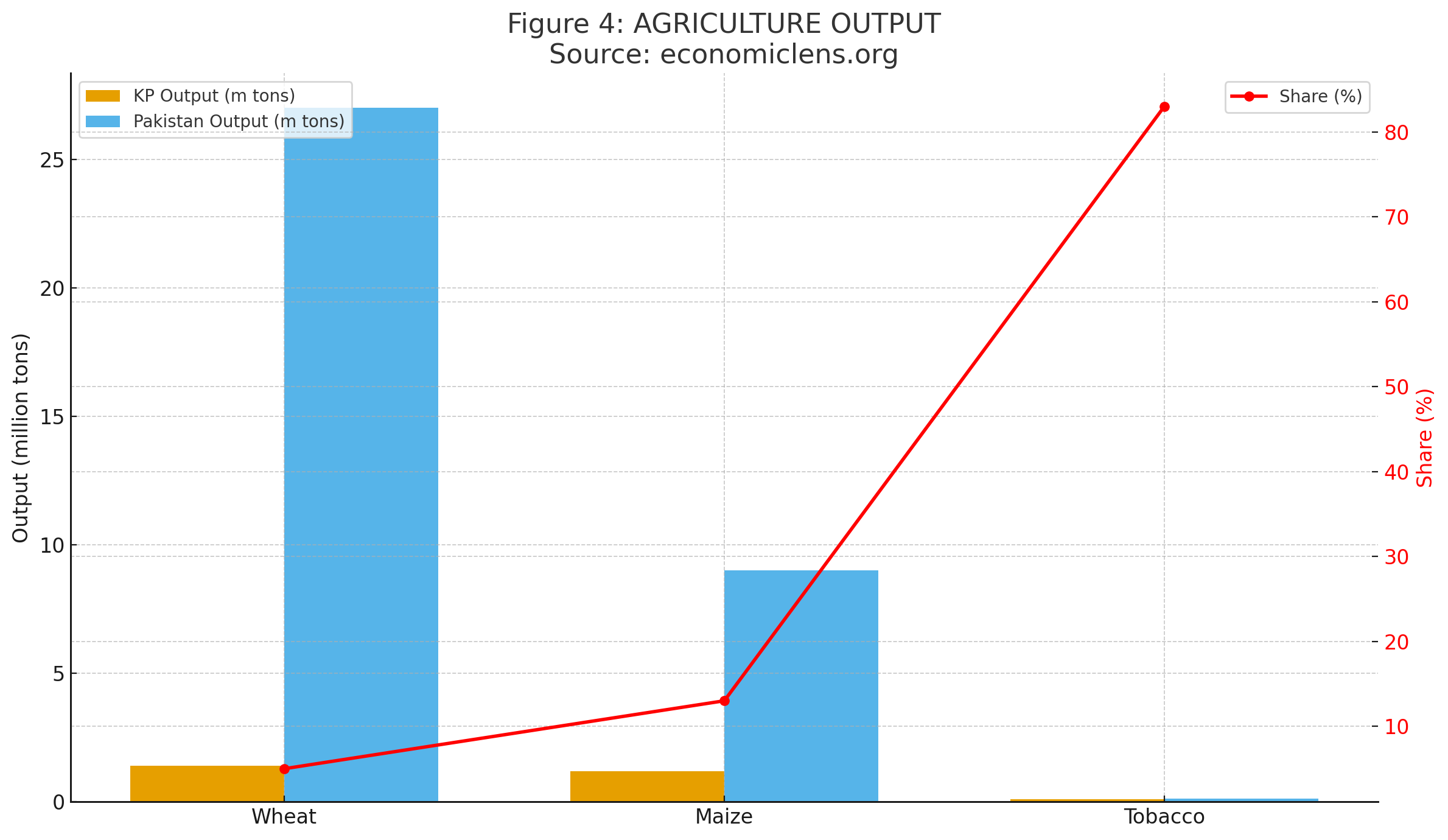

4. Agriculture & Food Systems in the Resource-Rich Region

Agriculture remains central to household income but suffers from low productivity. FAO highlights massive post-harvest losses, small landholdings, and outdated irrigation. Experts claim KP could become a horticulture powerhouse with cold-chain systems.

KP dominates tobacco, but lags in cereal yields. Horticulture modernization is key.

“Agriculture keeps KP alive — but agro-processing can make KP thrive.”

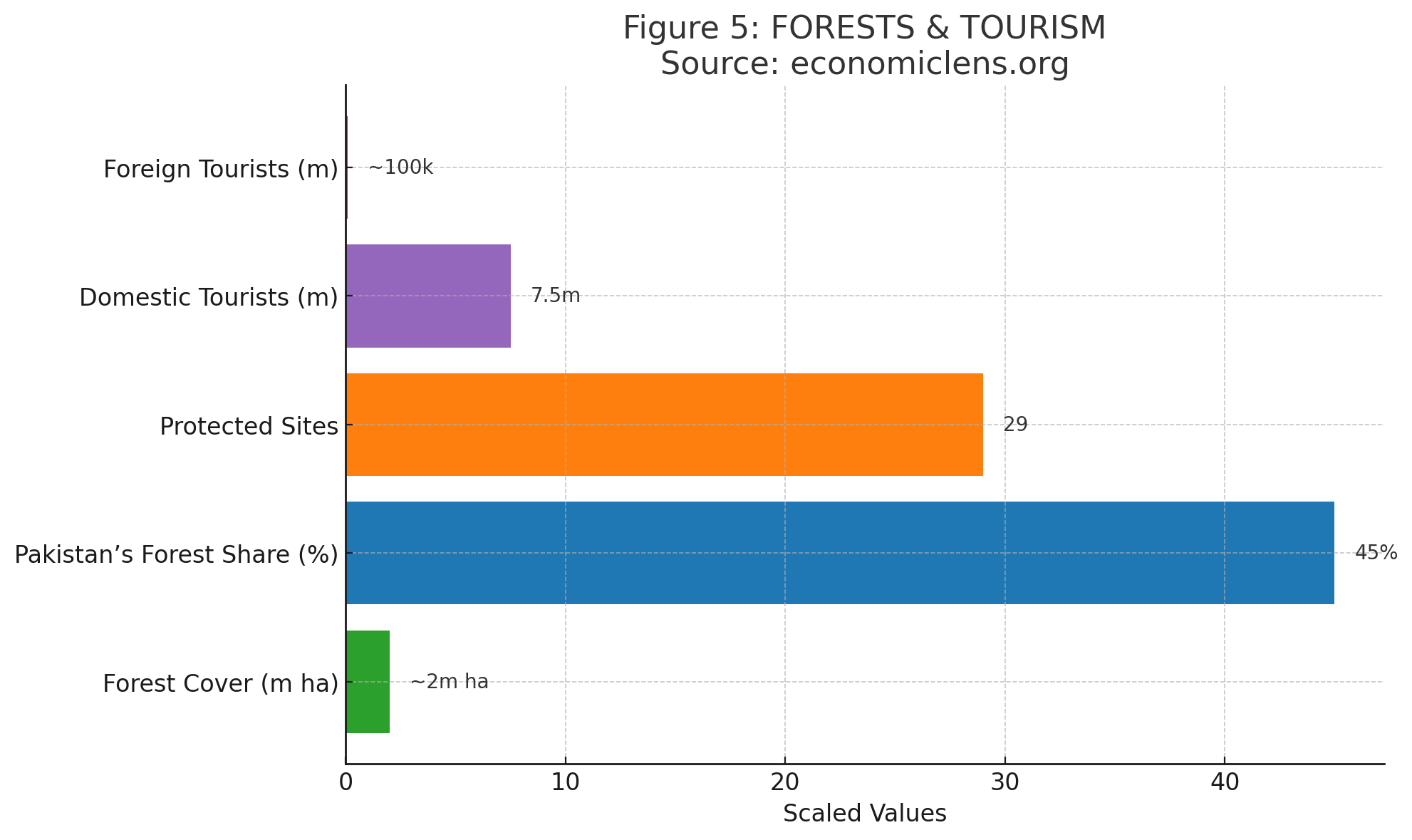

5. Forests & Eco-Tourism in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Economy

KP hosts Pakistan’s most scenic valleys — Swat, Chitral, Kaghan, Naran, Kumrat — and nearly half the forests. Tourism researchers argue that KP’s landscape is globally competitive, but infrastructure is not. Forestry departments warn that deforestation threatens hydropower and water security.

KP’s eco-tourism sector is vibrant but underdeveloped. International tourism remains extremely low.

“KP’s mountains are more than scenery — they are a sleeping economy waiting to wake.”

6. Cross-Border Trade & Informal Flows in KP

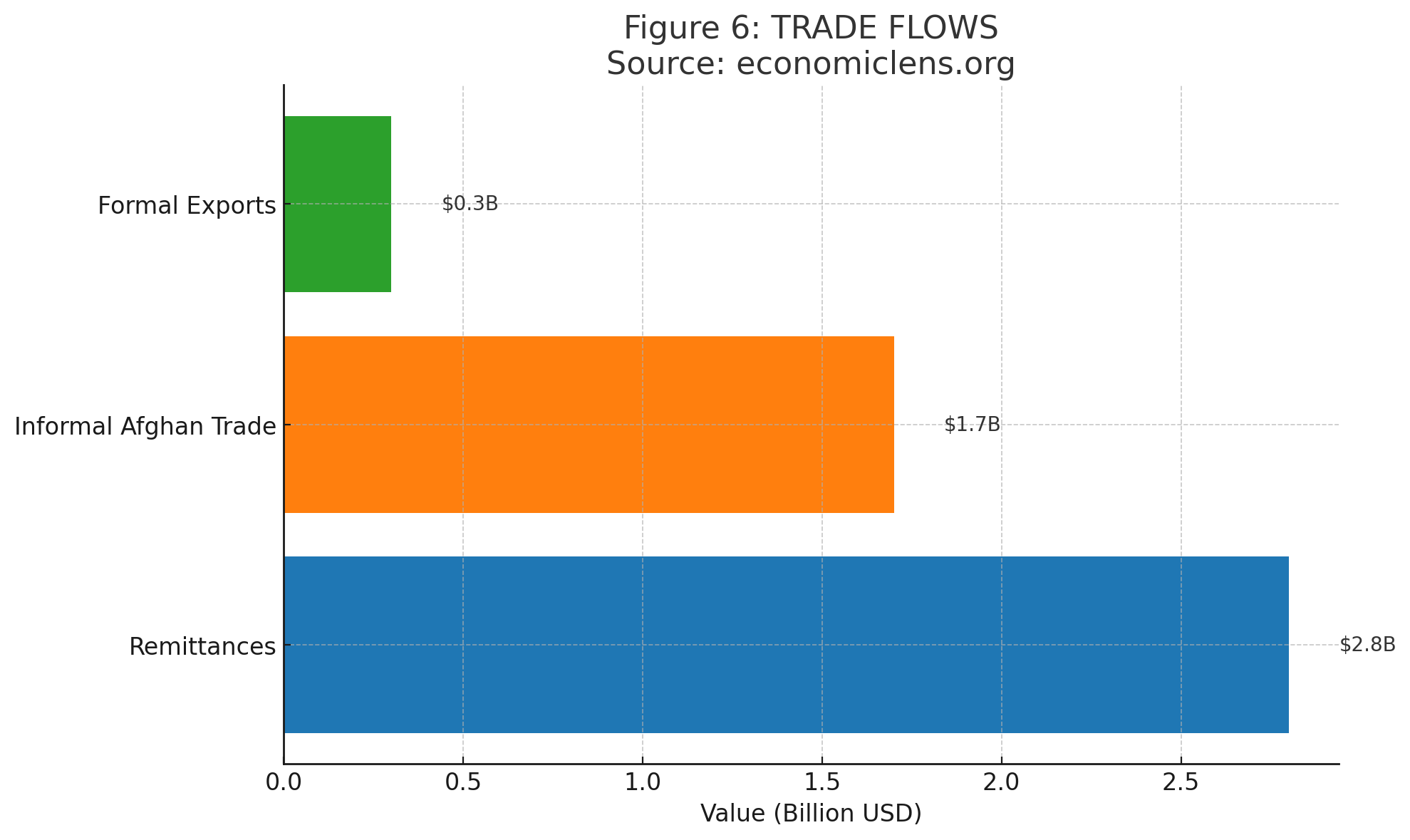

KP’s economy is deeply influenced by Afghanistan’s market, remittances from the Gulf, and cross-border commerce.

Trade experts highlight that informal Afghan trade keeps KP’s markets afloat but reduces government revenue. Migration analysts underline KP’s dependence on Gulf remittances.

KP’s economy relies heavily on external financial flows. Formalization could increase government revenue significantly.

“External money may sustain KP — but only internal growth can secure KP.”

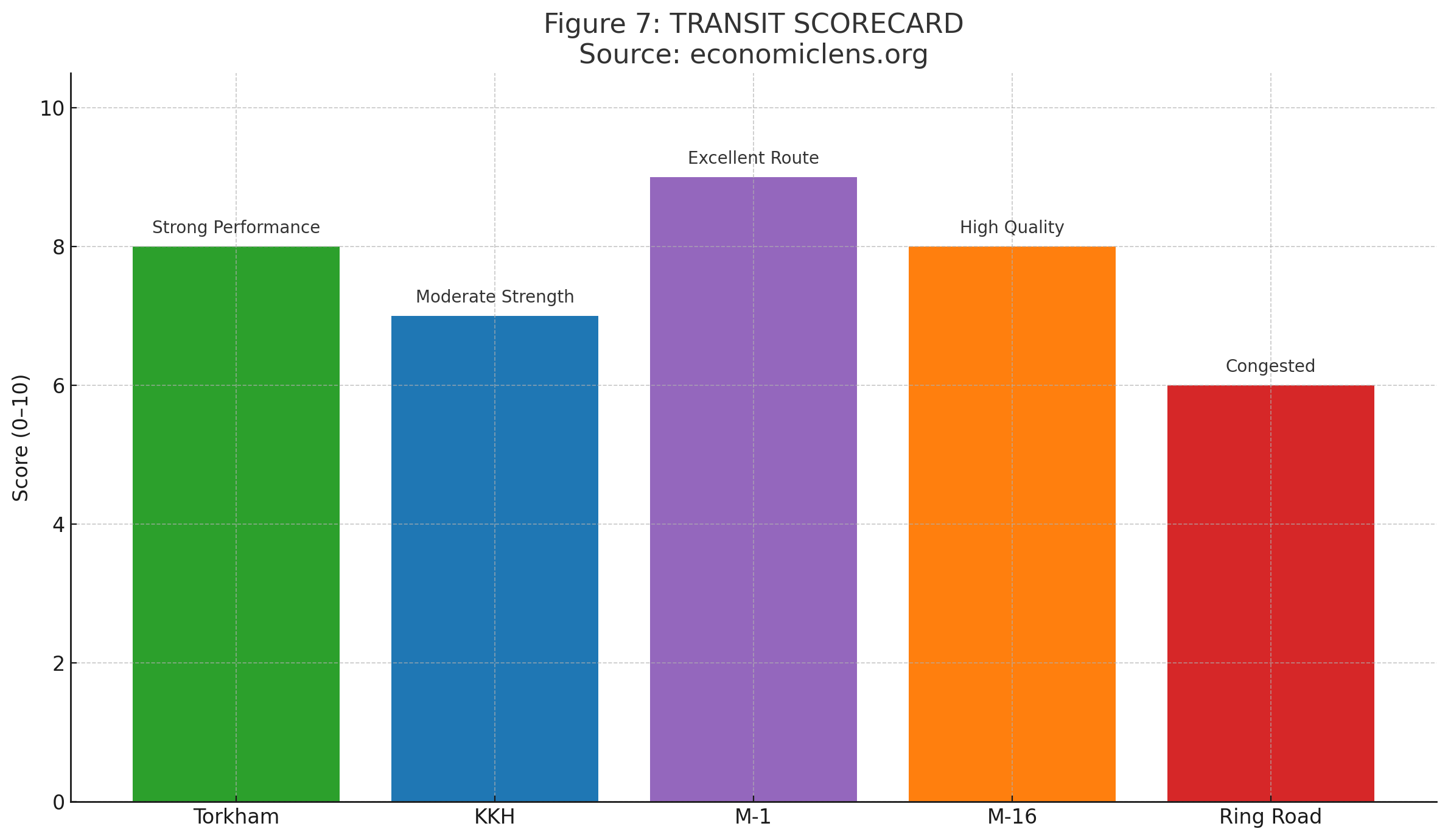

7. Connectivity, Corridors & Logistics in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Economy

KP sits on Pakistan’s key transit routes, linking domestic markets with Afghanistan and Central Asia. While major highways provide strong connectivity, the lack of logistics parks, cold storage, and industrial corridors limits KP’s ability to turn movement into meaningful economic value.

ADB notes that KP’s corridors are “strategically vital but underutilized,” mainly due to missing logistics infrastructure. World Bank assessments similarly highlight that without warehousing and cold-chain capacity, KP captures only a small share of the economic benefits its highways could generate

KP has solid highways but lacks logistics parks, cold storage, and industrial corridors.

“Roads bring goods into KP — but logistics bring prosperity out of it.”

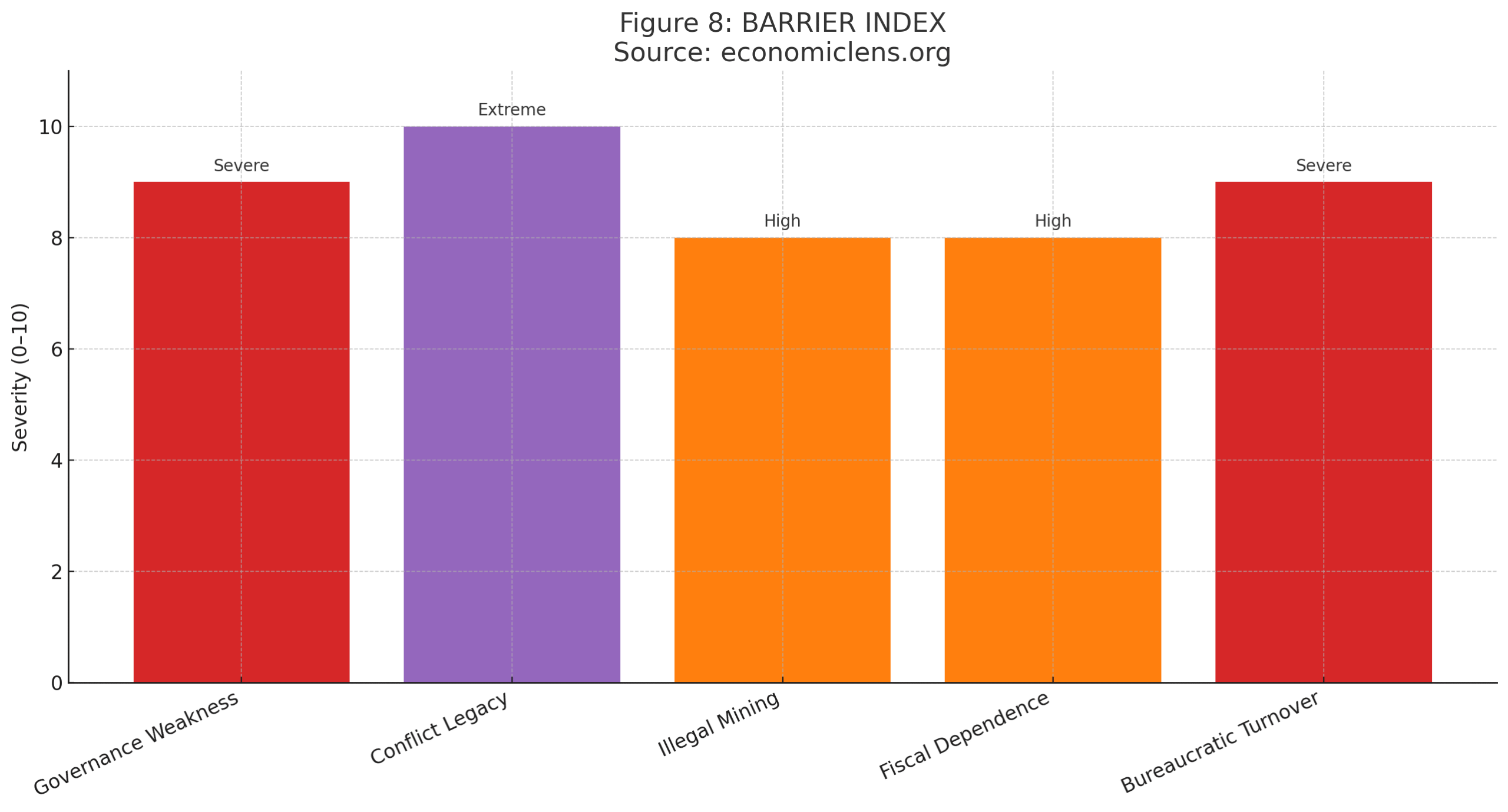

8. Structural Barriers Limiting the Resource-Rich Region

Despite immense natural wealth, KP’s economic progress is held back by structural constraints such as governance gaps, weak regulation, conflict legacy, and administrative turnover. These barriers limit how effectively resources are managed, processed, and converted into growth.

World Bank governance diagnostics note that KP’s economic potential is “restricted more by institutional weaknesses than by resource scarcity.” ADB assessments similarly highlight that inconsistent enforcement, informal markets, and conflict spillovers undermine long-term development.

KP’s underperformance is structural, not resource-based. Strong institutions are essential.

“No resource can overcome weak governance — but good governance can overcome every resource challenge.”

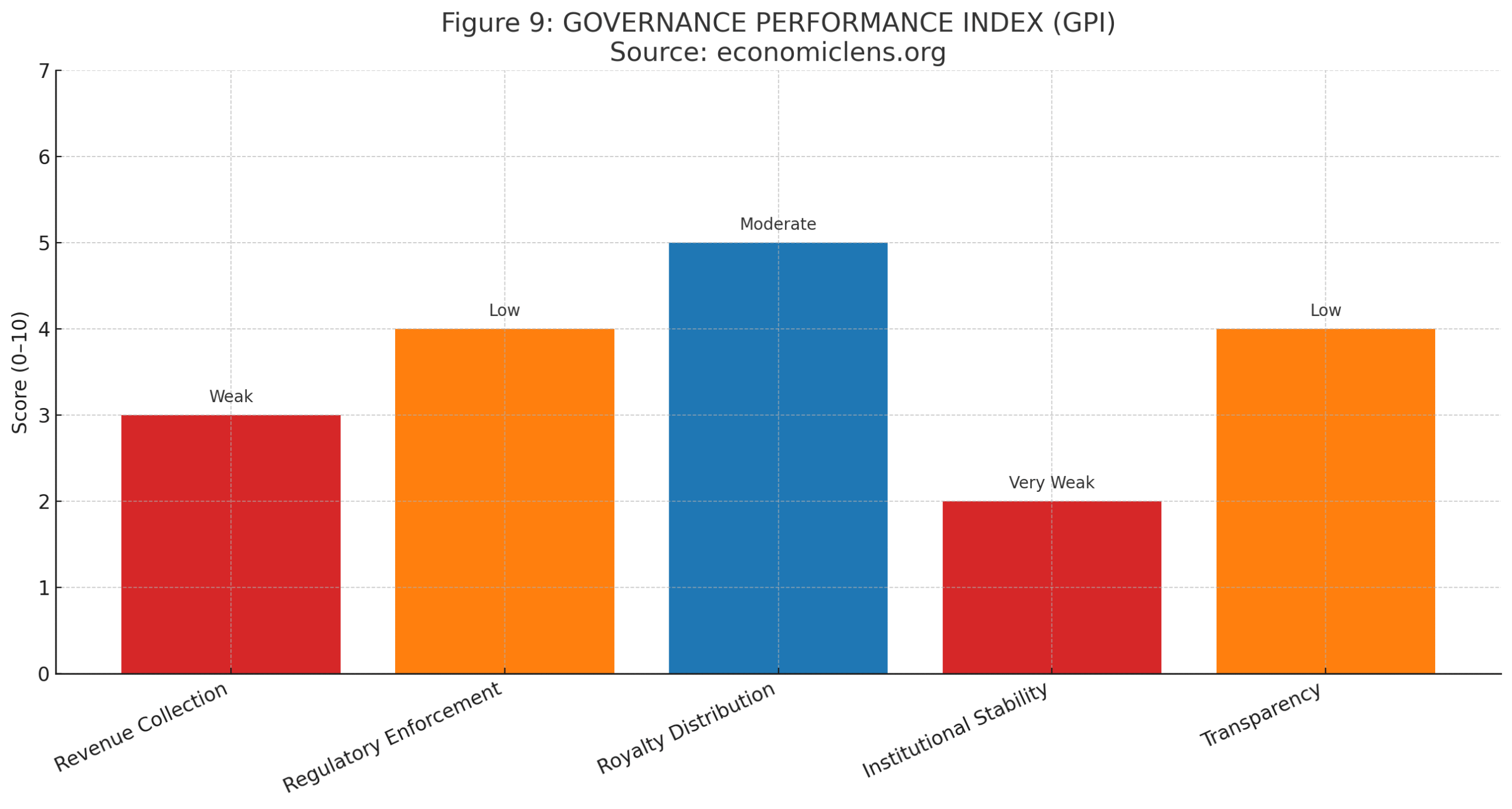

9. Governance Weaknesses Over 12–13 Years

Though KP enjoyed political continuity for over a decade, its governance systems did not mature accordingly. Frequent bureaucratic changes, fragmented institutions, and weak oversight stalled progress that long-term stability should have supported.

UNDP and PILDAT evaluations point out that KP’s governance reforms “remained shallow,” with institutional systems failing to match political stability. Reports stress that without administrative continuity and stronger regulatory frameworks, development outcomes cannot be sustained

Political continuity did not translate into administrative reform. The system remains fragile.

“Governance is not a slogan — it is the engine that drives every other engine.”

10. Reform Pathways for a Thriving Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Economy

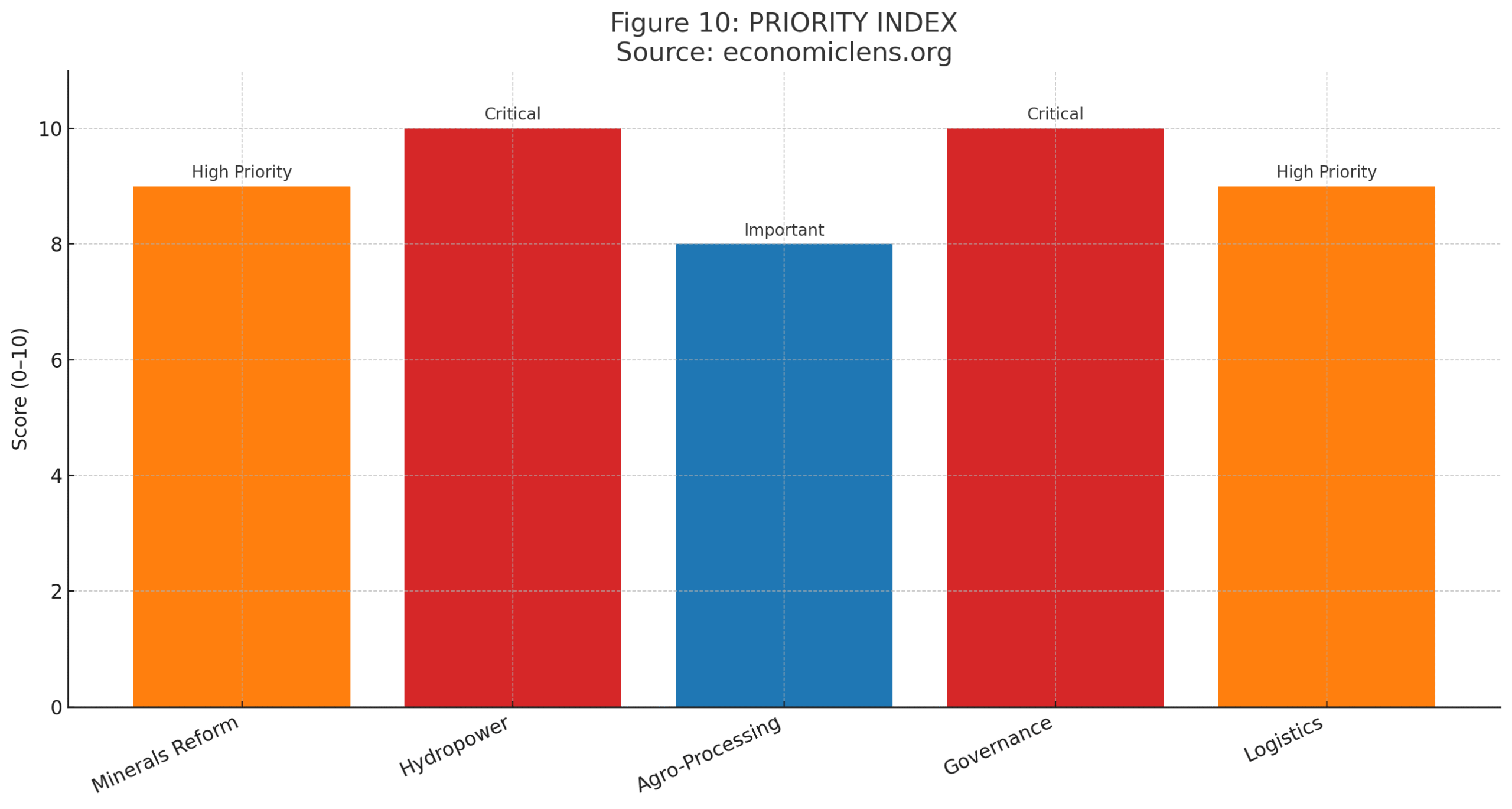

KP’s transformation depends on targeted reforms that unlock its natural strengths—modern mining, expanded hydropower, streamlined governance, and upgraded logistics. Strategic intervention in these areas can rapidly shift KP from extraction to value creation.

Economic reform studies by ADB and the World Bank emphasize that KP’s highest-impact gains come from industrializing minerals, accelerating hydel projects, digitizing governance, and improving trade infrastructure. These reforms, they note, “offer the fastest path to durable provincial growth.”

The fastest wins lie in hydropower, mining modernization, governance reform, and logistics upgrading.

“KP’s future will not be built by chance — it will be built by choices.”

Policy Implications

Transforming the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa economy from a resource-rich but underperforming region into a productive growth engine requires reforms that are coherent, realistic, and institutionally grounded. The first priority is strengthening governance. KP’s economic weakness is not due to a shortage of resources but a shortage of systems. Therefore, licensing, royalty collection, monitoring, and enforcement must shift from manual, fragmented processes to transparent, digital, and rule-based governance. Ensuring stable administrative tenures and strengthening institutional oversight will allow long-term plans to take root instead of resetting with every political or bureaucratic change.

A second major focus is the modernization of mining and industrialization. KP extracts minerals in large quantities, yet exports almost all of them raw. To correct this, the province must encourage mechanized mining, develop processing zones, and establish quality certification and testing facilities. Only then can KP convert its raw materials into finished products that generate higher employment, exports, and provincial revenue. Industrial investment in ferrochrome, marble processing, gypsum boards, ceramics, and engineered stone can create a value-added ecosystem capable of transforming KP’s economic trajectory.

Energy and hydropower reforms are equally critical. Because KP holds half of Pakistan’s hydel potential, accelerating hydropower development can create fiscal space, attract industrial investment, and reduce dependence on federal transfers. Resolving approval bottlenecks, improving coordination with federal agencies, and encouraging private-sector participation in oil, gas, and renewable energy will allow KP to leverage its natural advantage in power generation.

Agriculture and tourism, two of KP’s largest employment sectors, require targeted modernization rather than expansion alone. For agriculture, the creation of cold-chain networks, improved irrigation, and agro-processing will help farmers capture more value from what they already produce. For tourism, upgrading infrastructure, service standards, and conservation frameworks will lift KP from a low-value, domestic tourism zone to a globally competitive destination. Forest management, too, must shift toward sustainable models that protect ecosystems while creating new income streams through conservation incentives.

Finally, KP must build a modern trade and logistics architecture. Its strategic location demands efficient logistics hubs, better customs coordination, and improved cross-border systems to formalize trade with Afghanistan and Central Asia. Formalizing these flows will increase provincial revenue while reducing dependency on informal markets. Together, these reforms form an integrated roadmap that aligns governance, industry, energy, agriculture, tourism, and trade into a coherent development model. If implemented with consistency and political will, they can unlock the true potential of this resource-rich region and position the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa economy as a powerful driver of Pakistan’s future.

“KP does not need to discover new resources—it needs to discover new discipline. Real transformation will come not from the wealth in its mountains, but from the wisdom in its management.”

CONCLUSION

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa economy remains a paradox: a resource-rich region with exceptional natural wealth but chronically weak economic outcomes. KP has the minerals, forests, hydropower, agriculture, and geography to reshape Pakistan’s economic map, yet it continues to lag because institutions, systems, and governance never kept pace with its resources.

For decades, conflict, instability, fragmented governance, informal extraction, and low industrialization prevented KP’s resources from becoming real economic assets. Massive hydropower capacity remains underdeveloped, minerals leave the province unprocessed, agriculture lacks modern supply chains, and tourism remains infrastructure-deficient. Meanwhile, reliance on remittances and informal Afghan trade masked internal weaknesses instead of correcting them.

In reality, KP is not overlooked because it lacks value; KP is overlooked because it lacks conversion systems that turn value into prosperity. What held KP back is also what can propel it forward: its unmatched natural wealth, young population, and strategic location.

The path forward is clear: upgrading governance, modernizing extraction, accelerating hydropower, formalizing trade, and building industrial capacity. Once KP shifts from raw extraction to value addition, it will move from being Pakistan’s most overlooked goldmine to its most transformative engine of growth.

“KP is not poor because it lacks riches; KP is poor because its riches lack direction. When systems finally rise to meet its potential, this so-called frontier will become Pakistan’s frontier of growth.”

CALL TO ACTION

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa stands at a rare moment of opportunity. Its resources are abundant, its youth are capable, and its geography is strategically unmatched. What it needs now is coordinated action, not more time.

The next decade will decide whether KP remains a raw-material supplier or becomes a modern, value-driven economy. Industrialization, hydropower expansion, and governance reform can turn KP’s natural assets into long-term prosperity.

KP does not need new blessings, it needs new systems. If policymakers, investors, and communities commit to reform and modernization, KP will not only uplift itself, it will reshape Pakistan’s economic future. The goldmine is real. The moment to unlock it is now.

2 thoughts on “Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Economy: Why This Resource-Rich Region Is Pakistan’s Most Overlooked Goldmine”

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s economy is fundamentally shaped by its diverse geography — from glacier-fed mountains in the north to fertile plains in the center and mineral-rich dry zones in the south. This ecological variety creates distinct regional economic strengths, including tourism, hydropower, agriculture, mining, and trade. With nearly half of Pakistan’s forests and hydel potential, and strategic transit routes like the Khyber Pass, KP holds natural advantages unmatched in much of the region. In essence, its landscape forms a built-in economic blueprint, requiring only effective leadership and planning to fully unlock its potential.

Good Work ! 👏👍