The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis, also described as a Pak-Afghan border crisis, is reshaping regional trade, triggering economic losses, supply chain delays, security tensions, and declining access to Central Asia. This analysis explains the root causes, governance failures, smuggling networks, and policy reforms needed to restore stability and connectivity.

Introduction: Understanding the Pakistan–Afghanistan Border Crisis

The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis, widely described as a Pak-Afghan border crisis and an escalating Afghanistan transit disruption, has rapidly evolved into one of the most damaging diplomatic, economic, and security challenges in the region. Frequent border closures at Torkham and Chaman, increased documentation requirements, and rising security tensions have created severe disruptions in transit trade and cross-border mobility. These disruptions have slowed supply chains, raised costs for traders, and triggered widespread uncertainty in both countries. The crisis deepened further after Pakistan and the Afghan interim government failed to reach a consensus during the Qatar Doha negotiations. These talks were expected to stabilize tensions, but disagreements on security cooperation, transit regulation, biometric screening, militancy concerns, and the repatriation of undocumented Afghan nationals caused the dialogue to collapse.

During the Doha rounds, Pakistan sought enforceable commitments on TTP safe havens, full compliance with transit regulations, digital container tracking, and documentation for Afghan citizens. Afghanistan resisted these demands and insisted on relaxed movement rules, unrestricted transit, and minimal interference in internal matters. This diplomatic breakdown eliminated the final channel that could have prevented escalation, pushing the Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis into a prolonged impasse with deep economic consequences.

Experts from the World Bank and UNESCAP warn that the combination of border disruptions, deteriorating trust, and lack of cooperative enforcement has weakened regional connectivity. The World Bank (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/publication/connectivity-and-trade-facilitation-in-south-and-central-asia) notes that unstable border management and weak transit cooperation significantly raise trade costs, reduce job creation, and undermine regional integration across South and Central Asia. Both countries are now experiencing losses that affect everything from trade flows and local jobs to humanitarian conditions and regional diplomacy. Without a structured diplomatic process, the crisis threatens to become a long-term structural barrier to economic stability.

“Diplomacy was the bridge that could have prevented collapse, but its failure has turned cooperation into conflict. When nations stop talking, borders stop functioning and entire regions bear the cost.”

1. Historical Context of the Pak-Afghan Border Crisis

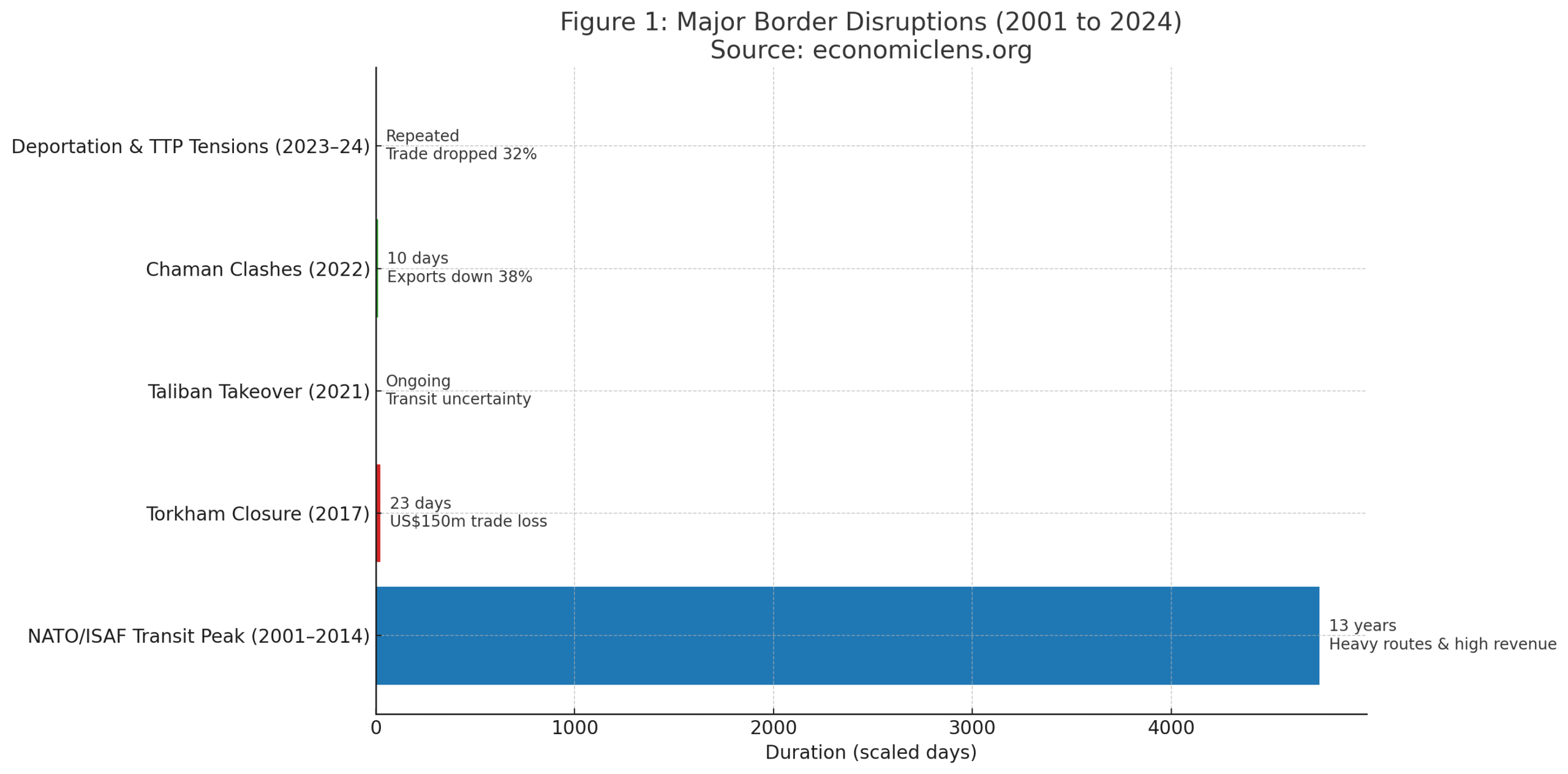

The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis is shaped by decades of historical tensions, political mistrust, and shifting regional priorities. The Durand Line dispute has been a persistent point of contention, influencing cross-border dynamics since the early twentieth century. After 2001, NATO and ISAF operations transformed the border into a major military logistics route, increasing traffic and revenue but also expanding smuggling and militancy. When international forces withdrew, commercial trade expanded but governance weaknesses became more visible. The Afghan Transit Trade Agreement and later APTTA attempted to regulate these flows, yet weak enforcement and political volatility ensured that border crises returned repeatedly. This long history created a fragile foundation that could not withstand the shocks of recent years.

According to regional historian Dr. Marvin Weinbaum, unresolved territorial disputes and mismatched political priorities have made border tensions inevitable. A SAARC transport connectivity study emphasizes that inconsistent enforcement of transit rules has repeatedly eroded trust, while the World Bank (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/publication/connecting-to-compete-trade-logistics-in-south-asia) highlights that weak institutional coordination has kept key trade corridors vulnerable to disruption. Together, these findings show that the crisis has deep historical roots and cannot be separated from long-term governance challenges.

The timeline shows that the crisis is not new but part of a long chain of disruptions linked to political transitions and security incidents. Every major shift has caused significant economic losses and weakened trust.

“A border shaped by history cannot escape the weight of its past. Unless the past is understood, no future solution will be strong enough to last.”

2. Root Causes of the Pakistan–Afghanistan Transit Trade Breakdown

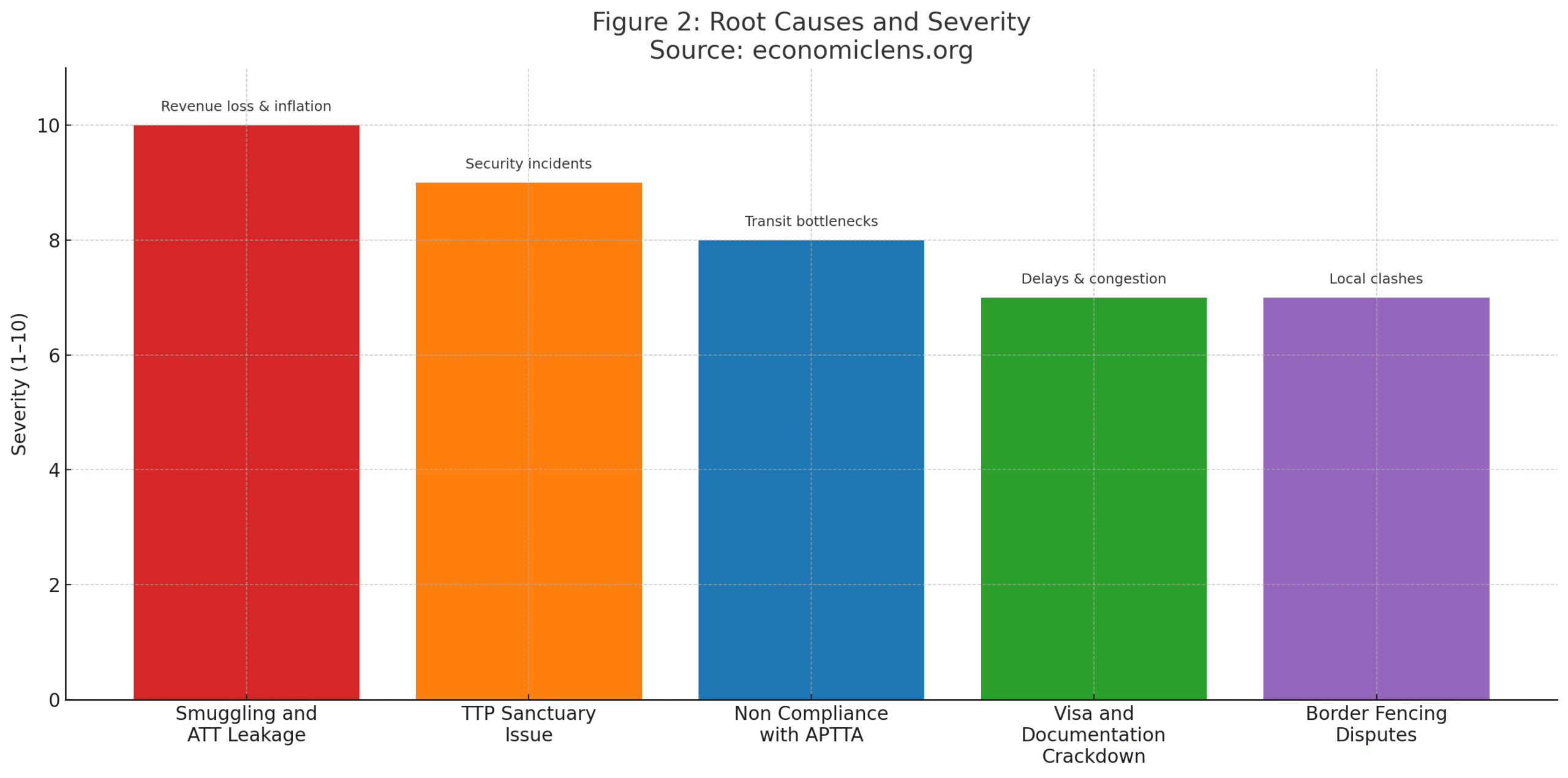

The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis stems from a combination of security concerns, economic distortions, smuggling, weak enforcement, and political disagreements. Pakistan has tightened documentation and transit rules to control smuggling and to address concerns about TTP militants operating from Afghan territory. Afghanistan opposes several of these measures, citing movement restrictions and economic pressures. The lack of mutually accepted enforcement mechanisms has turned daily border operations into flashpoints. As a result, transit trade is caught between national security priorities and unresolved political disagreements.

Security analyst Dr. Ayesha Siddiqa explains that the crisis reflects clashing priorities rather than temporary misunderstandings. Pakistan focuses on security and formalized trade, while Afghanistan prioritizes open movement and economic flexibility. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/drug-trafficking.html) reports that regional smuggling has increased since 2021 due to weak oversight and poorly coordinated border management. The International Monetary Fund (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/07/12/Pakistan-Staff-Report-for-the-2023-Article-IV-Consultation-and-Request-for-an-Extended-Arrangement-537344) warns that Pakistan’s fiscal stability depends on stronger customs regulation, making lax enforcement and transit abuse fiscally unsustainable.

The highest severity scores belong to structural issues like smuggling and militancy. These challenges require long-term solutions and cannot be fixed through short-term agreements or temporary concessions.

“When root causes remain unaddressed, crises repeat themselves in sharper and more destructive forms. The border cannot stabilize until the foundations beneath it are repaired.”

3. Key Drivers of Pak-Afghan Security and Trade Conflict

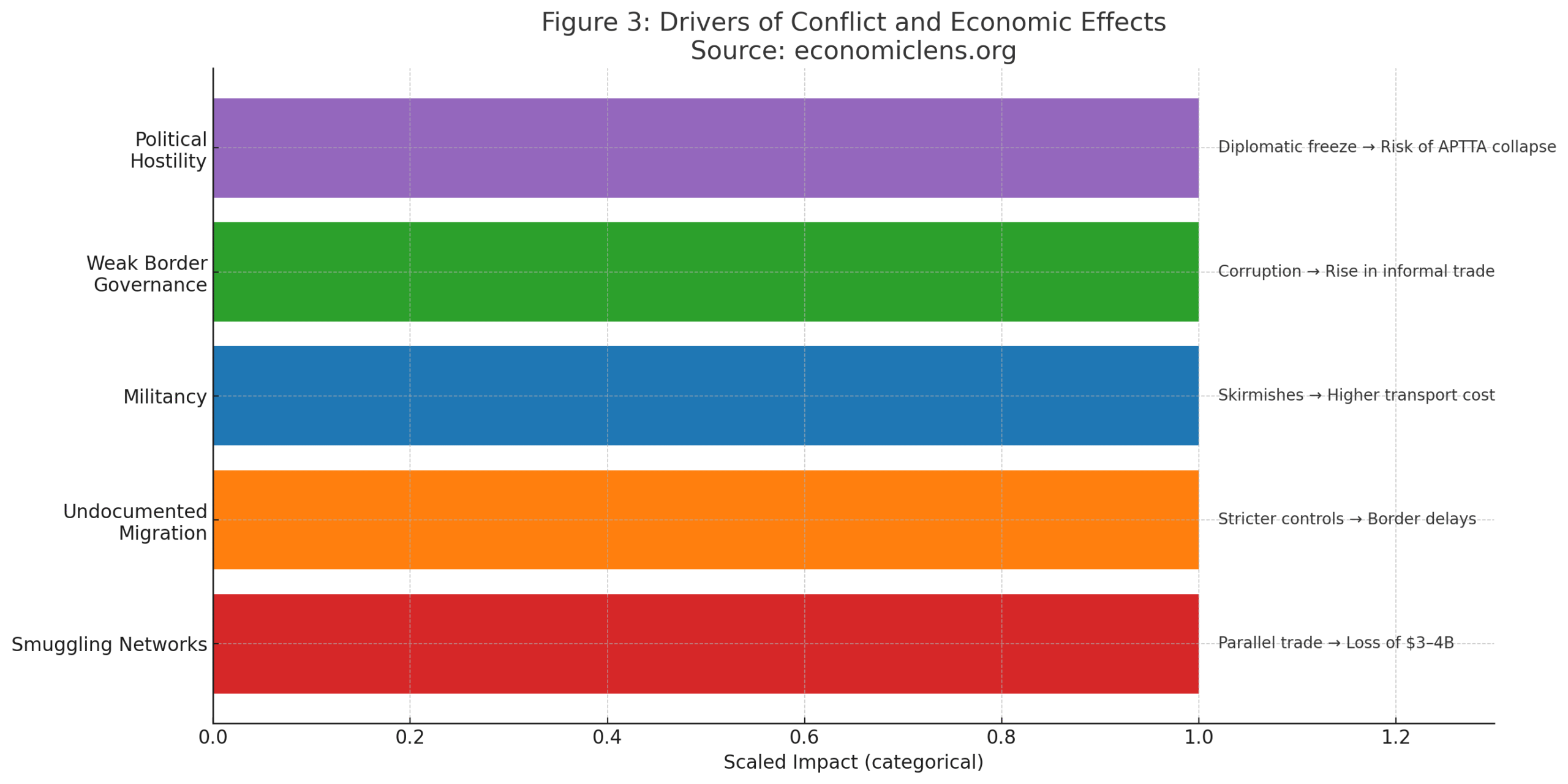

The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis is escalating due to several accelerating drivers. These include divergent security priorities, conflicting economic incentives, the dominance of informal economies, militant activity, and political mistrust. Pakistan’s attempts to regulate cross-border movement through digitization clash with Afghan concerns about mobility constraints. Meanwhile, powerful smuggling networks oppose regulation, and militant groups exploit gaps in border control. These forces combine to keep tensions high and cooperation low.

Border governance specialist Dr. Kamal Alam notes that Pakistan and Afghanistan operate under incompatible economic systems, making regulatory alignment extremely difficult. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (https://www.unescap.org/kp/2021/trade-facilitation-digitalization-and-cross-border-paperless-trade-asia-pacific) shows that Afghanistan’s limited customs digitization creates operational friction, while Pakistan’s rapid enforcement of tracking systems widens the capacity gap. The International Crisis Group (https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/pakistan) confirms that sudden policy tightening in fragile border environments often triggers immediate spikes in tension and confrontation.

Each driver contributes directly to the instability of the trade corridor. Their combined impact undermines bilateral relations and weakens the broader regional supply chain.

“When multiple forces collide, borders transform from gates of opportunity into walls of division. Stability requires addressing every driver, not just the most convenient one.”

4. Smuggling and Transit Abuse Behind the Afghan Border Economic Fallout

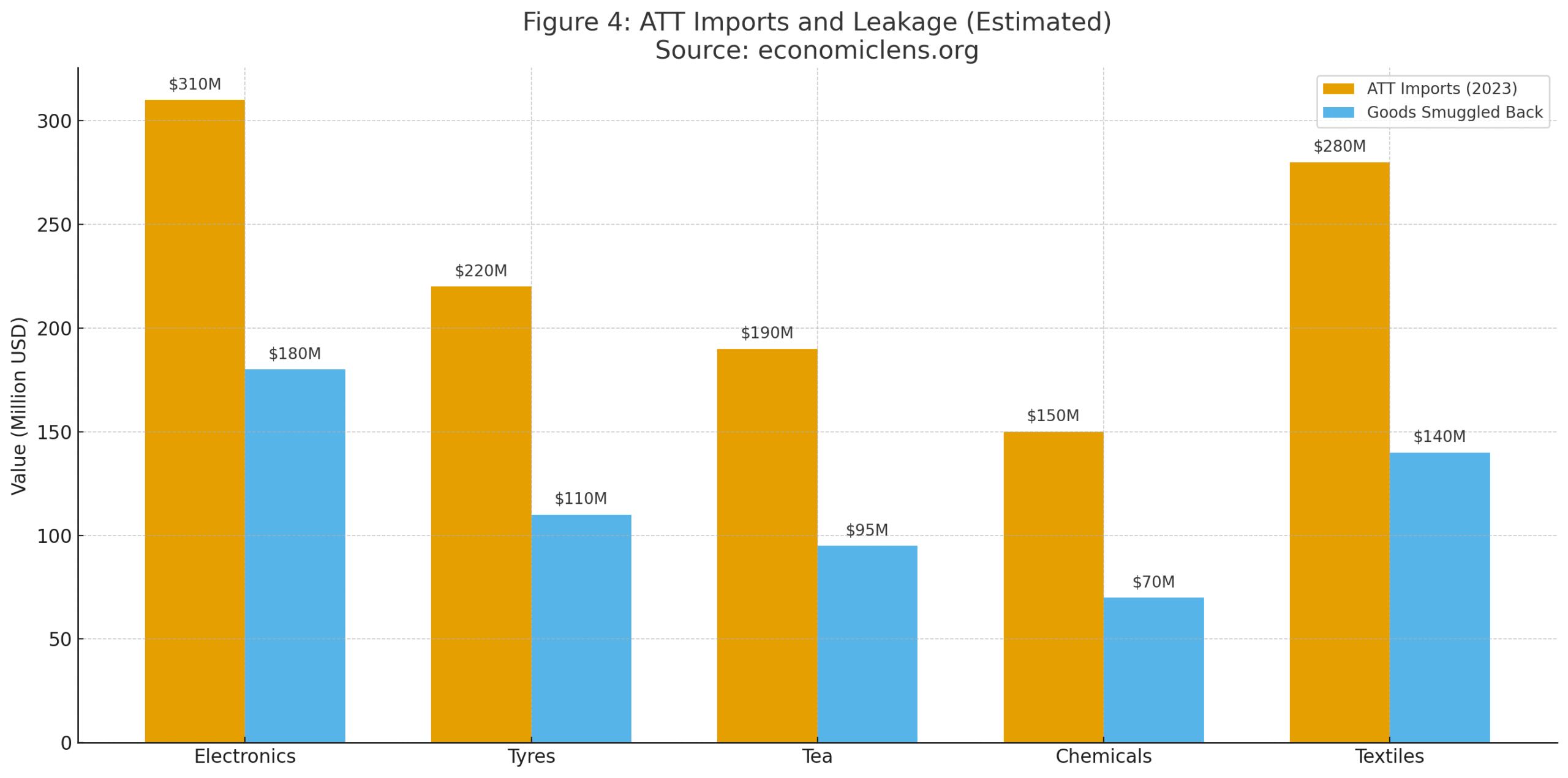

Transit abuse under the Afghanistan Transit Trade system is one of the most significant contributors to the Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis. For years, goods imported duty free into Afghanistan have been smuggled back into Pakistan, harming local industries and causing major revenue losses. As Pakistan introduces stricter customs controls, including digital tracking and sealed containers, influential smuggling networks resist compliance. This clash between regulation and profit fuels tension at every checkpoint.

FBR analysts estimate that 35 to 50 percent of high value ATT goods leak back into Pakistan. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (https://unctad.org/topic/trade-logistics-and-facilitation) confirms that the Afghanistan Transit Trade re export system forms one of the largest informal economies in South Asia, driven by weak Afghan customs enforcement and porous border routes. The World Bank (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/publication/trade-facilitation-and-logistics-reforms) attributes much of this leakage to the absence of sealed container mechanisms, weak tracking systems, and limited cross border coordination.

The figures demonstrate that smuggling is a systemic challenge, not an isolated problem. This leakage distorts domestic markets, reduces revenue collection, and undermines the rationale for liberal transit frameworks.

“Where illegal profit outweighs legal trade, stability becomes impossible. A border shaped by smuggling cannot support economic growth.”

5. Governance Failures Fueling Pak-Afghan Trade Tensions

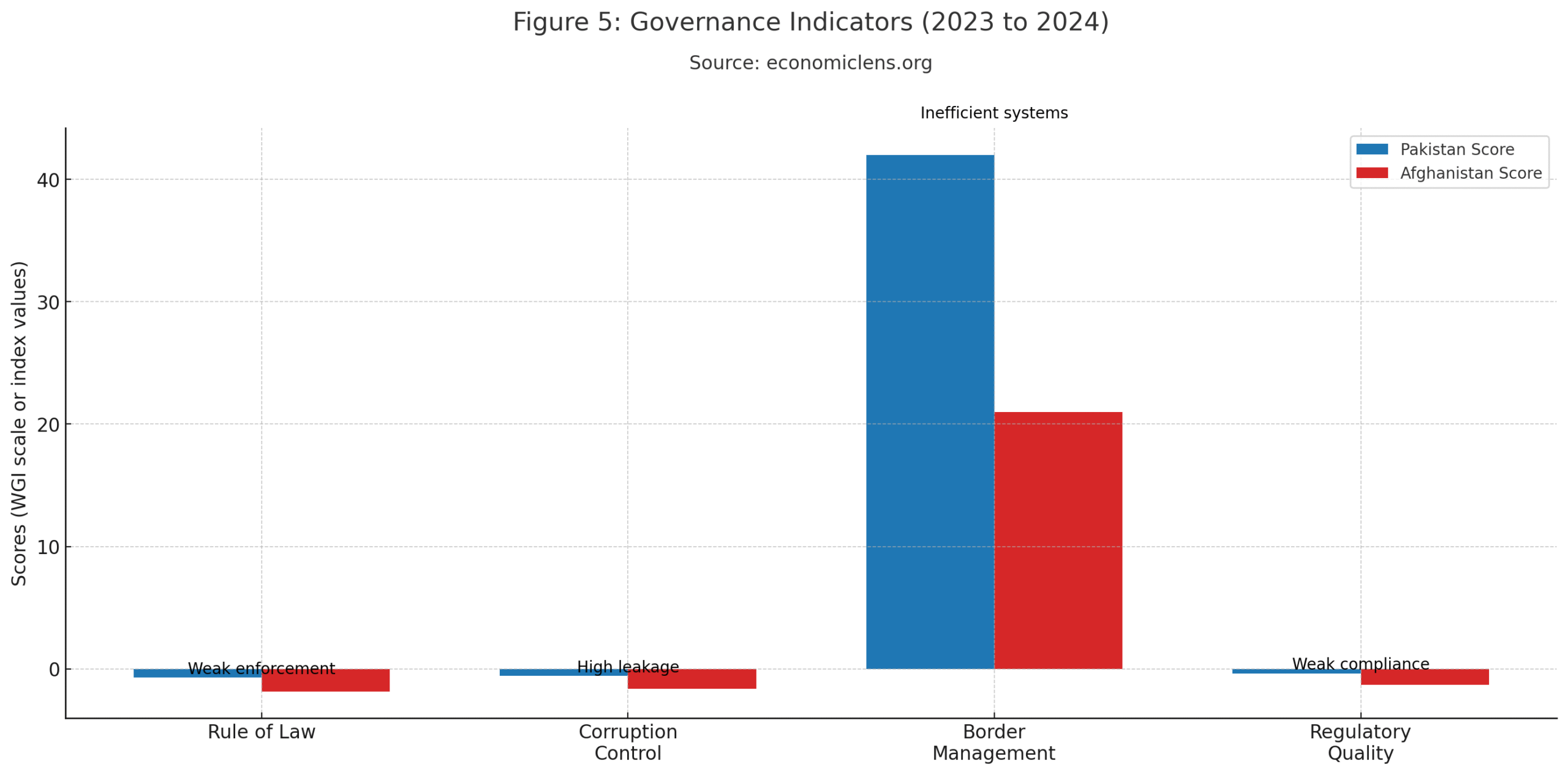

Weak governance is a core challenge driving the Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis. EconomicLens (https://economiclens.org/kp-governance-crisis-security-turmoil-border-disruptions-and-institutional-decay/) documents how governance breakdowns, security pressures, and institutional decay in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have directly undermined border administration, enforcement capacity, and crisis response mechanisms. Pakistan faces bureaucratic delays, coordination gaps, and enforcement limitations. Afghanistan struggles with severe institutional fragility, underfunded customs operations, and limited monitoring systems. These weaknesses allow smuggling, corruption, and evasion to flourish, damaging trust and complicating policy reforms. Without institutional coordination, no agreement can withstand operational realities.

Governance expert Dr. Ishrat Hussain emphasizes that sustainable border management requires strong institutions on both sides. The World Bank’s World Governance Indicators (https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/) reveal systemic weaknesses in regulatory quality, rule of law, and corruption control across Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project (https://www.v-dem.net/data/the-v-dem-dataset/) further notes that Afghanistan’s post-2021 institutional environment lacks the stability, administrative capacity, and rule-based governance needed for effective border management.

The governance gap between the two countries makes synchronized border operations extremely difficult. Without institutional stability, enforcement efforts cannot be effectively harmonized.

“Strong borders depend on strong institutions. Weak governance invites chaos and turns every checkpoint into an opportunity for exploitation.”

6. Economic Costs of Afghanistan Transit Disruption

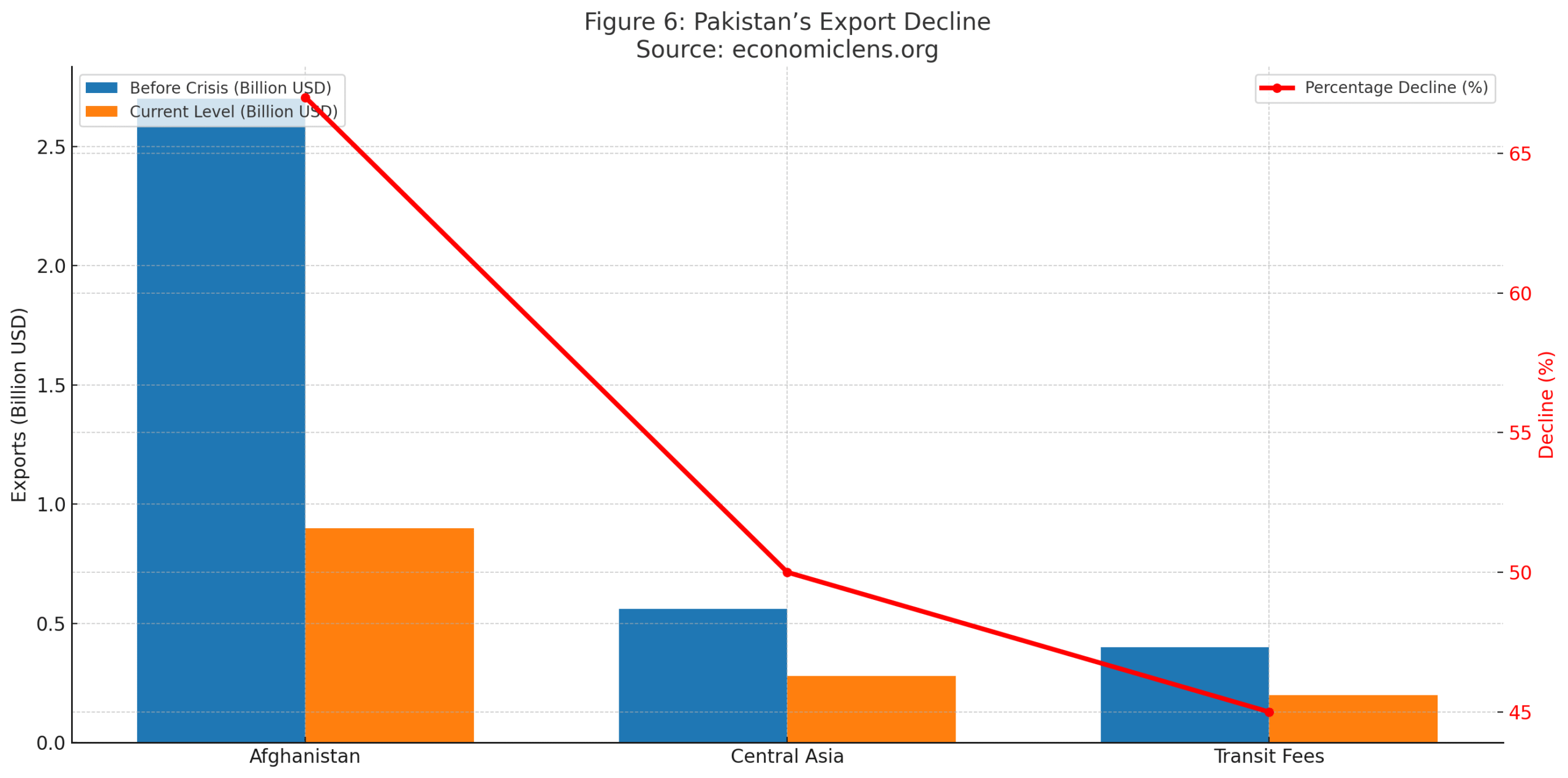

The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis has inflicted heavy economic losses across both countries. EconomicLens (https://economiclens.org/pakistan-economic-instability-a-structural-diagnosis/) highlights that repeated external shocks, weak institutions, and chronic fiscal stress have already left Pakistan economically fragile, making border disruptions far more damaging than in stable economies. Bilateral trade has fallen sharply, cross border transport costs have surged, and Pakistan’s access to Central Asia has narrowed. Traders face increased delays and rising freight charges, while Afghan consumers encounter inflation and shortages. Border communities on both sides have suffered job losses and reduced commercial activity as supply chains stall.

Economist Dr. Kaiser Bengali notes that losing the Afghan market has weakened Pakistan’s export diversification strategy. The World Bank (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/publication/pakistan-trade-and-competitiveness-diagnostics) shows that Pakistan’s transit revenue has dropped by nearly half due to repeated border disruptions and the rerouting of cargo toward Iranian corridors. For Afghanistan, the United Nations Development Programme (https://www.undp.org/afghanistan/publications/afghanistan-economic-monitor) reports that import inflation has risen significantly as border restrictions slow the entry of essential commodities and disrupt supply chains.

Pakistan’s export losses reflect the vulnerability of regional trade to political disruptions. Reduced access to Central Asia further threatens Pakistan’s long term geo economic plans.

“Every closed border weakens the region’s economic foundation. Unless stability returns, Pakistan and Afghanistan risk losing markets that may never fully come back.”

7. Militancy, Security Risks and Pak-Afghan Connectivity Crisis

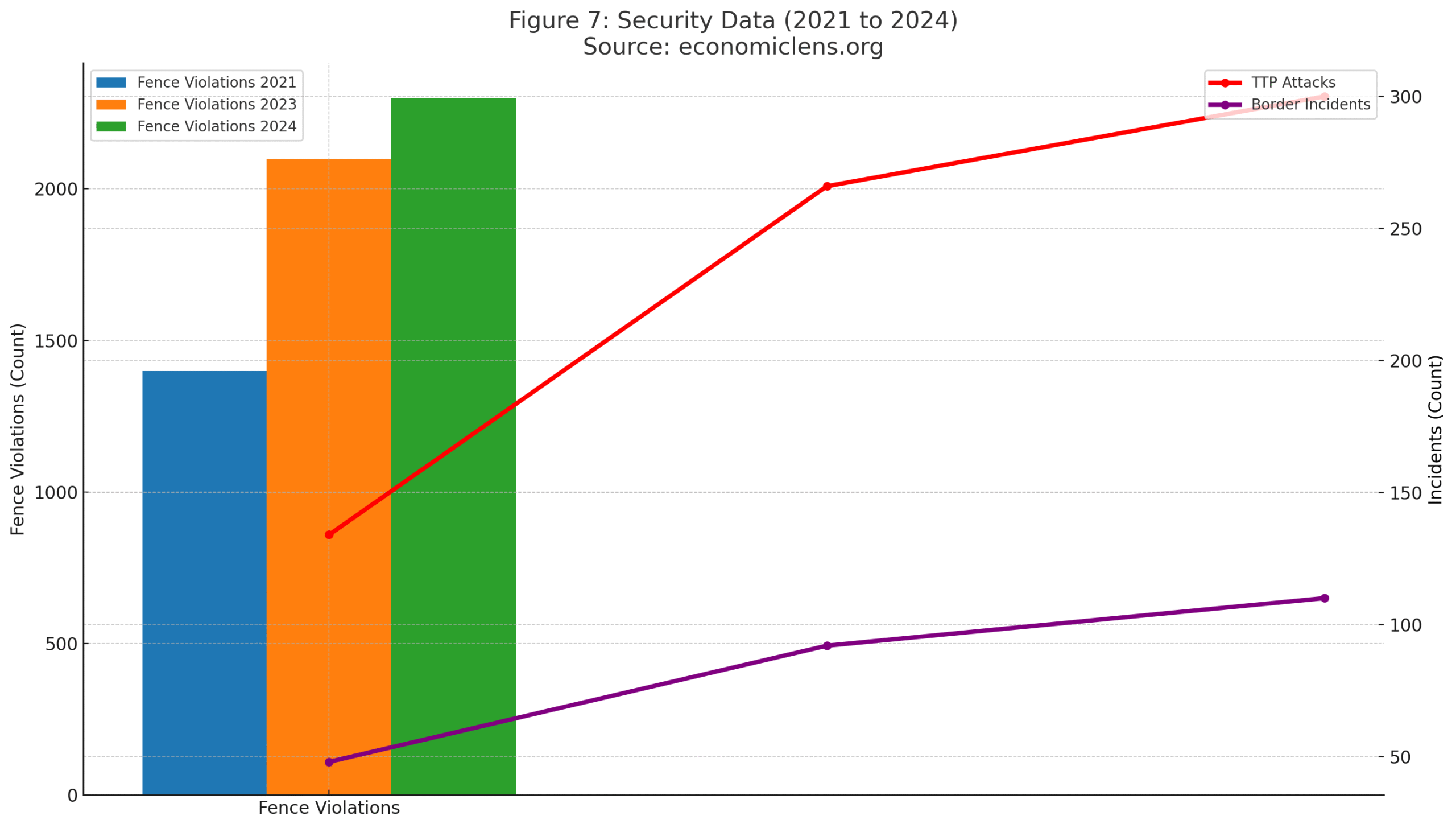

Security concerns lie at the center of the Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis. Pakistan accuses TTP militants of using Afghan territory to launch attacks, prompting tighter border security and stricter documentation rules. Afghanistan rejects these accusations and argues that Pakistan’s policies restrict economic activity and movement. The lack of a joint security mechanism has intensified mistrust and turned routine incidents into major diplomatic confrontations.

Security analyst Muhammad Amir Rana emphasizes that TTP activity shapes Pakistan’s border policies more than any other single factor. The United Nations Security Council (https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/reports) confirms that TTP fighters remain active in eastern Afghanistan and continue to target Pakistani security forces, heightening cross-border security risks. The Afghanistan Analysts Network (https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/security/) notes that weak and unclear security coordination between the two sides has allowed militant activity to directly influence border operations and disrupt trade flows.

The rising number of militant incidents and border clashes directly contributes to trade disruptions, delays, and closures. Security and economics are inseparable in this crisis.

“There can be no trade without security, and no security without cooperation. Until militancy is addressed, the border will remain unstable.”

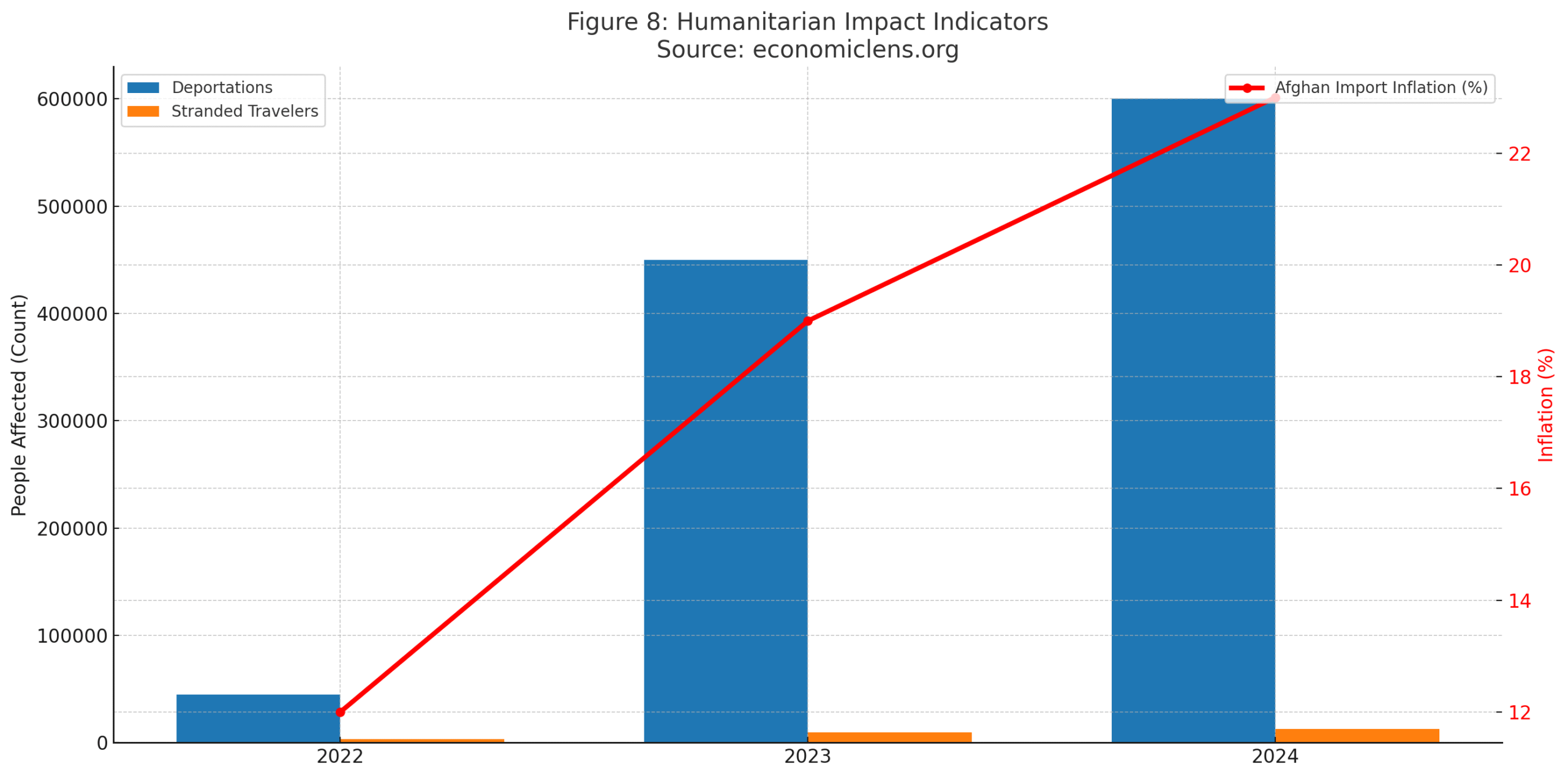

8. Humanitarian Impact of Afghanistan Regional Connectivity Challenges

The humanitarian dimension of the Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis is substantial. Stricter border controls have stranded thousands of travelers, disrupted family connections, and affected patient access to medical treatment. The deportation of undocumented Afghans has placed heavy pressure on Afghan communities already struggling with unemployment and inflation. Border closures have also reduced earnings for transport workers, vendors, and laborers.

UNHCR reports that the return of hundreds of thousands of undocumented Afghans has strained community resources and social safety nets. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (https://www.unhcr.org/afghanistan.html) documents that large-scale returns have placed heavy pressure on housing, health services, and local labor markets in border regions. The International Organization for Migration (https://www.iom.int/migration-crisis-afghanistan) observes that volatile border conditions worsen humanitarian vulnerabilities on both sides, creating new challenges for families dependent on cross-border livelihoods and informal economic activity.

The human cost of the crisis continues to rise, creating long term social consequences that reach far beyond trade and transit.

“When borders harden, lives are disrupted. The humanitarian impact shows that the cost of this crisis is not measured in numbers alone.”

9. Central Asia Access Losses from the Pakistan–Afghanistan Transit Trade Breakdown

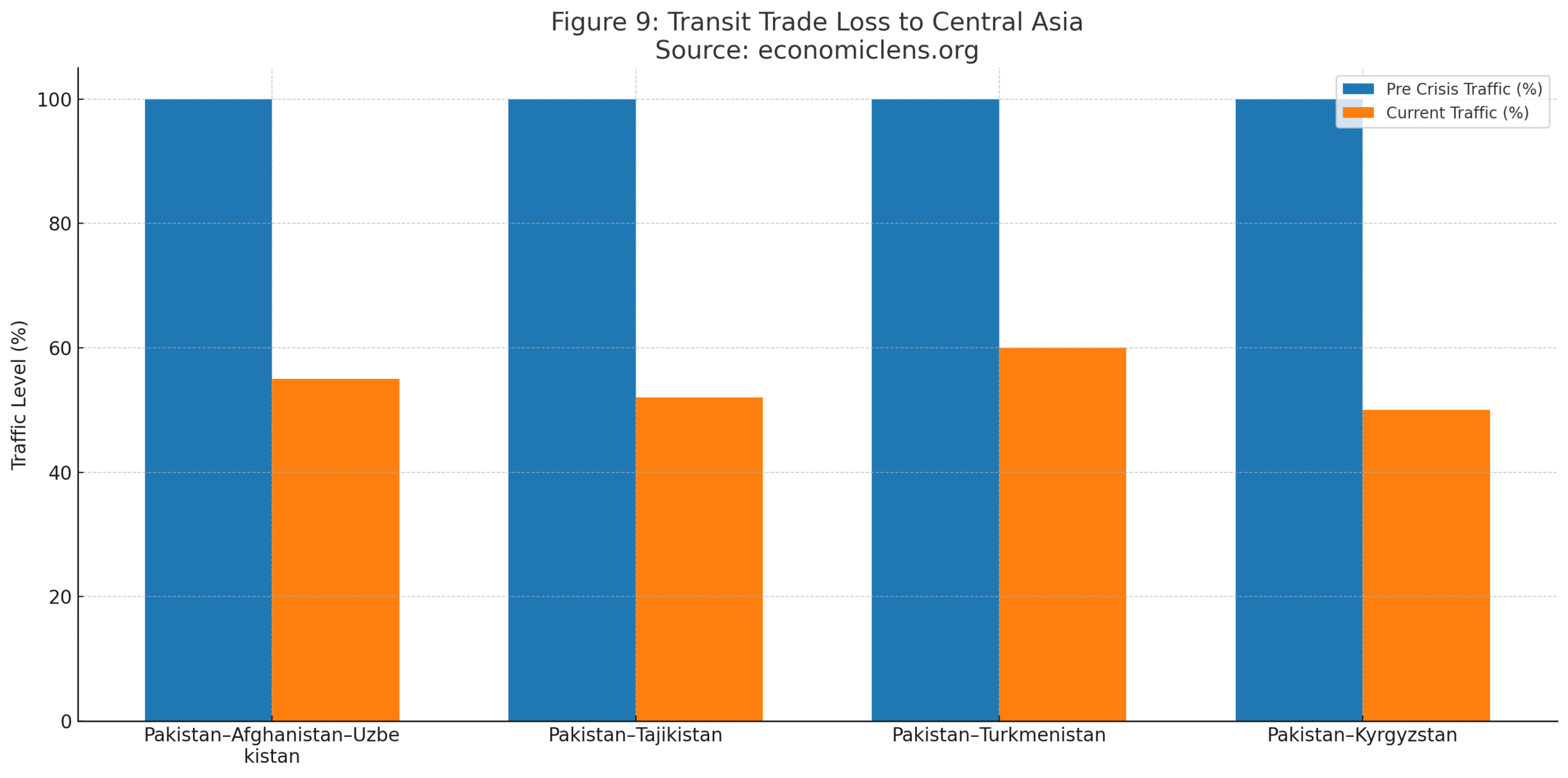

Transit trade through Afghanistan is Pakistan’s only land route to Central Asia. The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis has sharply reduced traffic, increased transport costs, and weakened Pakistan’s credibility as a regional corridor. Central Asian buyers increasingly prefer Iranian routes through Chabahar and Bandar Abbas due to greater predictability. This shift threatens Pakistan’s broader geo economic ambitions.

A UNESCAP corridor study shows that Pakistan’s access to Central Asian markets has declined by nearly half due to persistent border instability. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (https://www.unescap.org/kp/transport/corridors-and-connectivity) documents that unreliable border management significantly weakens regional corridor performance and trade competitiveness. Stratfor (https://worldview.stratfor.com/) analysts note that Iran has capitalized on Pakistan’s disruptions by offering more predictable transit routes through Chabahar and Bandar Abbas. China’s hesitation to expand CPEC through Afghanistan is also linked to border volatility, as unstable security and governance conditions raise investment and operational risks.

The decline in Pakistan’s transit traffic underscores the strategic cost of instability. Lost cargo flows often do not return even after conditions improve.

“Connectivity drives competitiveness. Without reliable transit routes, Pakistan cannot achieve its regional economic vision.”

10. Regional Geopolitics Amid the Pak-Afghan Border Crisis

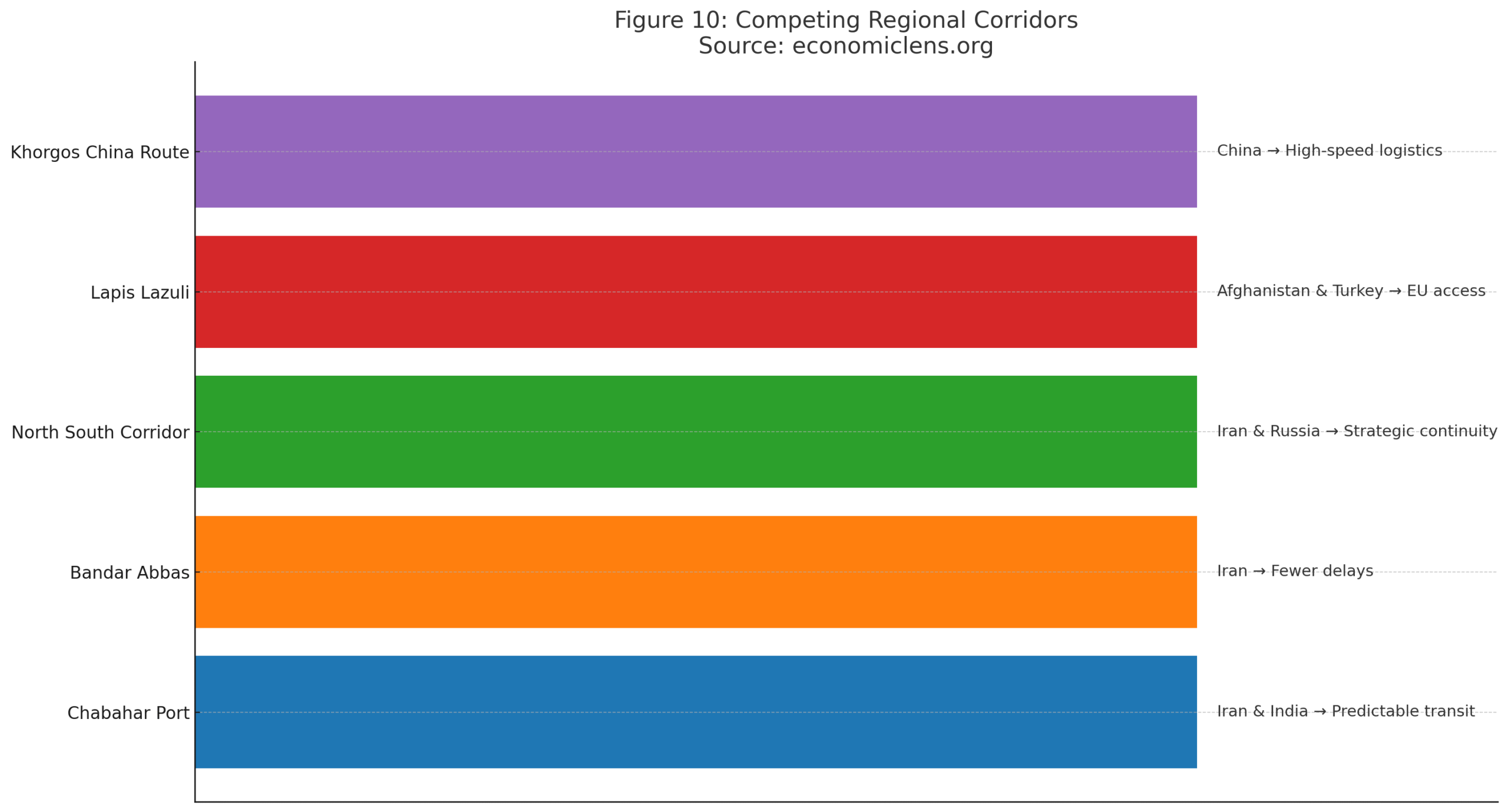

The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis has shifted regional trade dynamics. Iran’s Chabahar and Bandar Abbas ports are attracting more traffic, while Russia’s North South Corridor offers new options for Eurasian connectivity. Central Asian states are diversifying away from Pakistan due to instability. India and China are recalibrating their strategies in response.

Geopolitical analyst Dr. Andrew Small notes that unstable borders create opportunities for alternative routes to dominate. The World Bank (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/transport/publication/corridors-for-development) finds in its corridor comparison studies that competing trade routes offer more consistent transit timelines, lower political risk, and greater reliability for freight operators. As Pakistan faces recurring border crises, regional freight patterns adjust accordingly, shifting cargo flows toward corridors perceived as more predictable and secure.

As neighboring countries strengthen their corridors, Pakistan risks being bypassed in long term regional planning.

“Geography provides opportunity, but reliability creates influence. Pakistan must stabilize its borders to remain relevant in regional trade.”

11. Future Scenarios of the Pak-Afghan Connectivity Crisis

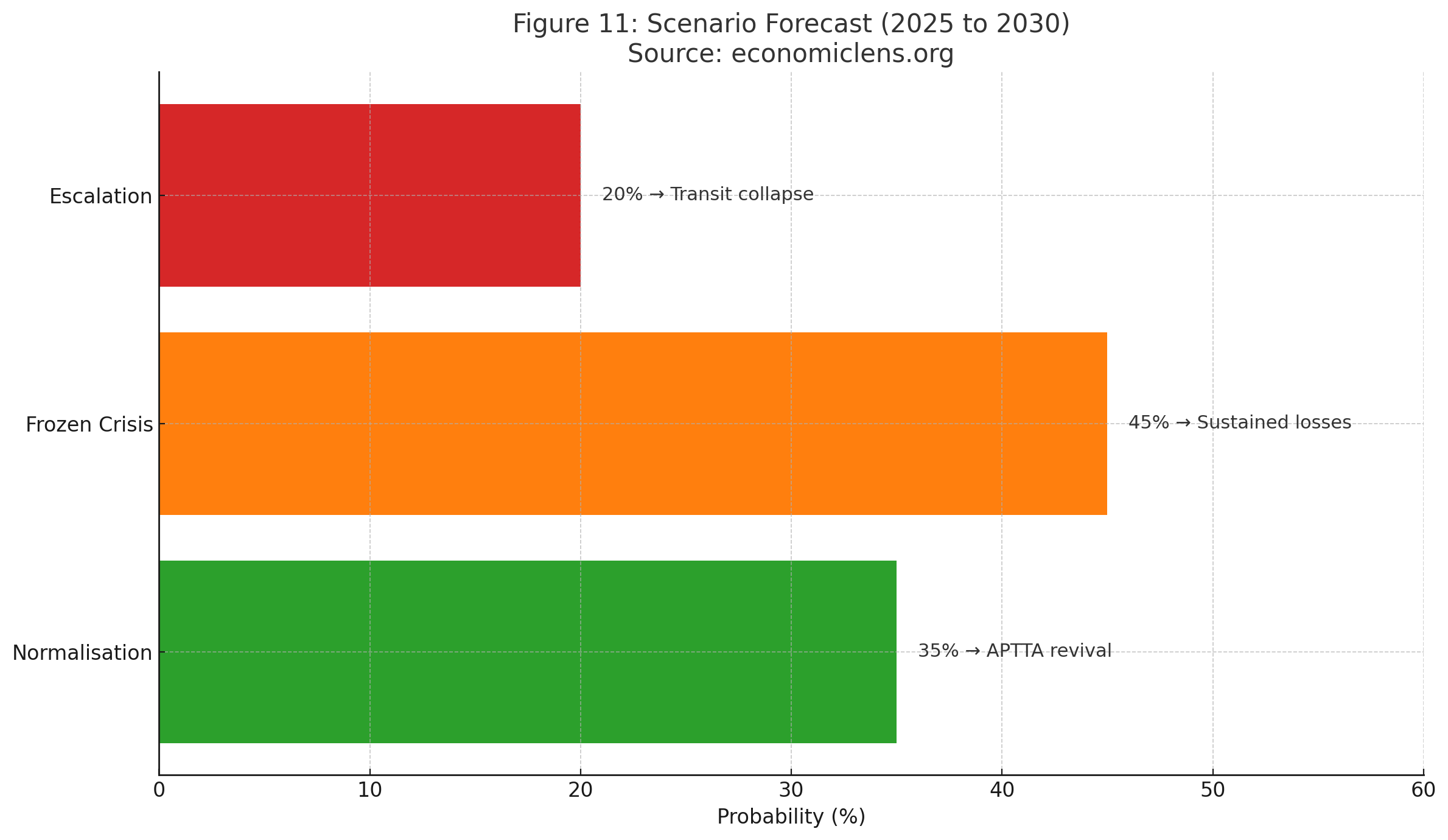

The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis could evolve in multiple directions. The most optimistic scenario involves structured dialogue and predictable border management. The more likely scenario is a prolonged stalemate with recurring disruptions. The worst case scenario involves escalation that collapses the remaining transit framework.

Stratfor forecasts that without structured cooperation, a frozen conflict is the most probable outcome. UNESCAP notes that regional transit can improve only if both countries implement matching governance reforms. International Crisis Group warns that further deterioration in security cooperation could trigger new rounds of confrontation.

The most probable scenario suggests that without deliberate action, current tensions will continue and may worsen over time.

“The future depends on choices made today. Without proactive engagement, stability will remain out of reach.”

12. Policy Pathways for Stabilizing the Border

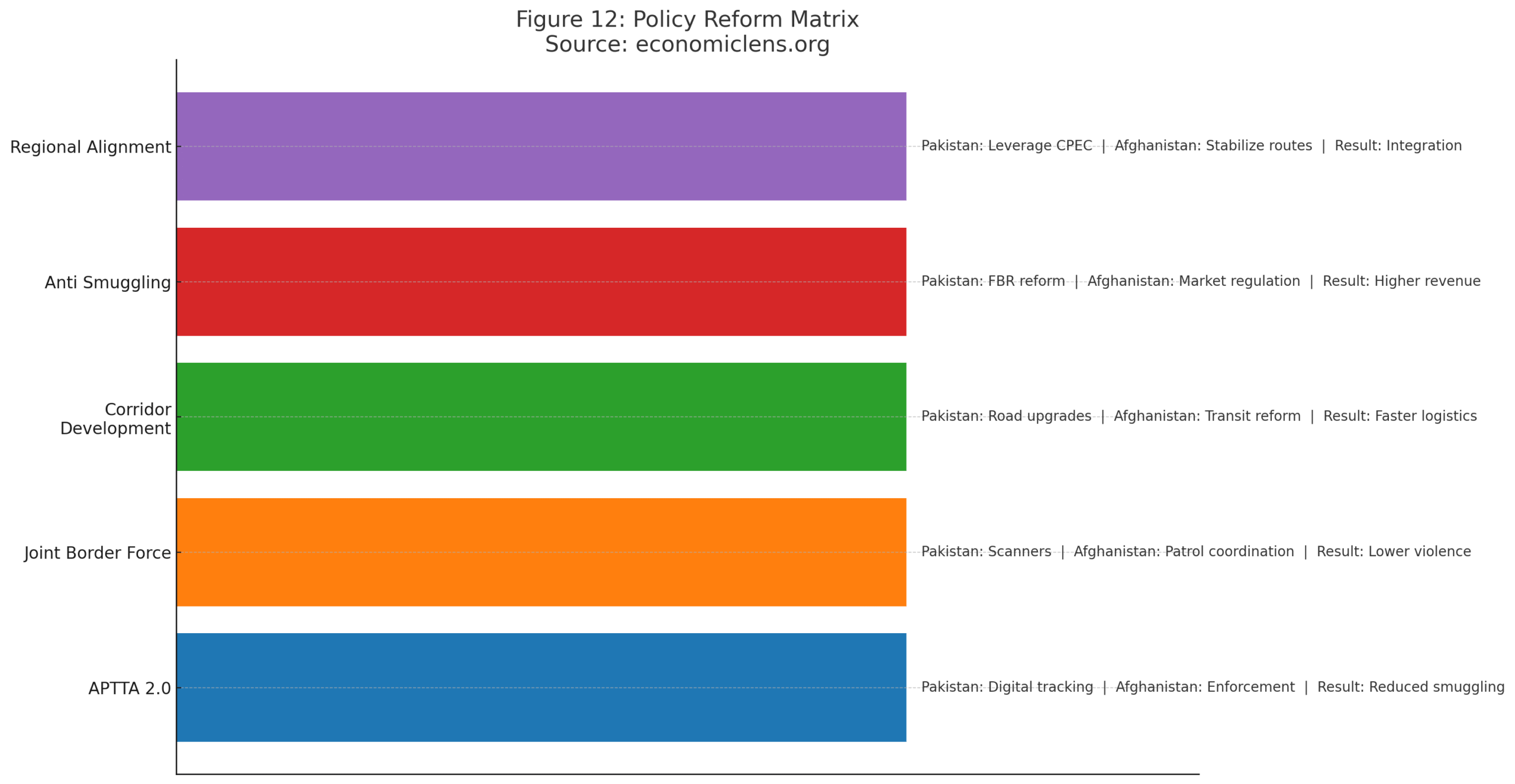

Resolving the Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis requires coordinated action, improved governance, and renewed diplomacy. Both countries must recognize that economic stability and regional connectivity depend on predictable borders. A framework that combines digital monitoring, joint enforcement, and transparent transit rules is necessary for long term stability.

ADB and UNESCAP experts argue that sustainable corridor management requires harmonized customs systems and joint monitoring teams. The World Bank (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/publication/trade-facilitation-and-logistics-reforms) notes that even strong trade agreements fail when they are not supported by modern border infrastructure, digital customs systems, and synchronized enforcement across agencies. Improved governance on both sides is therefore essential for ensuring predictable transit, lower trade costs, and long-term corridor stability.

Policy reforms require parallel efforts. Pakistan’s enforcement reforms must be complemented by strengthened Afghan oversight for results to materialize.

“Effective solutions require more than promises. When both sides align governance with economic vision, real progress becomes possible.”

Policy Implications

The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis shows that temporary fixes and unilateral enforcement cannot resolve structural problems rooted in smuggling networks, weak governance, and divergent security priorities. Stabilizing the border requires parallel reforms, not isolated actions. Pakistan and Afghanistan must adopt a coordinated framework built on digital tracking, joint enforcement teams, predictable documentation systems, and transparent transit rules. Without synchronized oversight, smuggling incentives and capacity gaps will continue to undermine every agreement.

Diplomacy must be revived as the central stabilizing tool. The collapse of Doha talks removed the only structured dialogue mechanism, turning operational disputes into political confrontations. A renewed negotiation track—focused on security cooperation, transit regulation, and humanitarian management—is essential to avoid a prolonged “Frozen Crisis” that weakens both countries. Equally important is institutional strengthening: Pakistan must modernize customs and anti-smuggling systems, while Afghanistan requires international support to rebuild functional border governance.

Finally, Pakistan must reclaim its regional connectivity footprint. Competing corridors in Iran, Russia, and China are expanding because they offer predictability that Pakistan currently cannot. Restoring trust at Torkham and Chaman is therefore not just a bilateral priority—it is a strategic necessity for Pakistan’s long-term geo-economic relevance.

“Borders shape destiny: if stability is delayed, Pakistan risks losing markets, influence, and opportunities that may never return.”

Conclusion

The Pakistan–Afghanistan border crisis has become a defining challenge for regional trade, security, and diplomacy. The failure of Doha negotiations eliminated the last formal channel for structured dialogue, deepening mistrust and worsening economic fallout. If current trends continue, both countries risk long term economic isolation and diminished regional influence. Cooperation, not confrontation, is the only pathway to restoring stability and unlocking regional potential.

“The cost of inaction rises with every passing month. Stability will return only when both sides choose cooperation over conflict and progress over paralysis.”

Call to Action

It is essential for policymakers, economists, and regional institutions to actively restore communication channels, strengthen border governance, and prioritize practical solutions. The future of regional trade and connectivity depends on decisions made today. Structured dialogue, coordinated security efforts, and transparent enforcement can revive trust and rebuild shared opportunity.