The Sri Lanka debt crisis shows how fiscal weakness, foreign exchange shortages, creditor complexity, and delayed restructuring led to default. This data-driven analysis explains causes, IMF-led stabilization, social costs, and lessons for emerging economies facing rising debt stress.

Introduction

The Sri Lanka debt crisis stands as one of the clearest modern warnings for emerging economies under financial stress. It shows how weak revenue capacity, rising external debt, and fragile foreign exchange buffers can converge into sovereign default. In 2022, Sri Lanka suspended external debt payments after reserves collapsed and inflation surged. Although stabilization followed under an IMF program, recovery remains fragile and politically constrained.

This episode reflects a broader debt cycle affecting developing economies, as discussed in (https://economiclens.org/debt-defaults-imf-rescue-programs-a-new-crisis-for-developing-economies/) .

1. Why the Sri Lanka Debt Crisis Matters for Emerging Economies

The Sri Lanka debt crisis followed a familiar emerging market sequence. Over time, fiscal revenues weakened while debt accumulated faster than economic growth. As a result, external borrowing increasingly became the main stabilizing mechanism. However, when global interest rates rose and capital flows reversed, refinancing channels closed rapidly. Consequently, foreign exchange reserves collapsed, and ultimately, sovereign default became unavoidable.

Importantly, this pattern now threatens many IMF-supported economies. For example, Pakistan’s repeated IMF engagements illustrate how temporary stabilization can coexist with deep and persistent fiscal fragility, as examined in Pakistan’s debt emergency and IMF bailouts on EconomicLens (https://economiclens.org/pakistans-debt-emergency-imf-bailouts-fiscal-stress-the-road-to-recovery/). At the global level, the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report warns that tighter financial conditions are amplifying sovereign risk across emerging markets, increasing vulnerability to rollover stress and debt distress (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR).

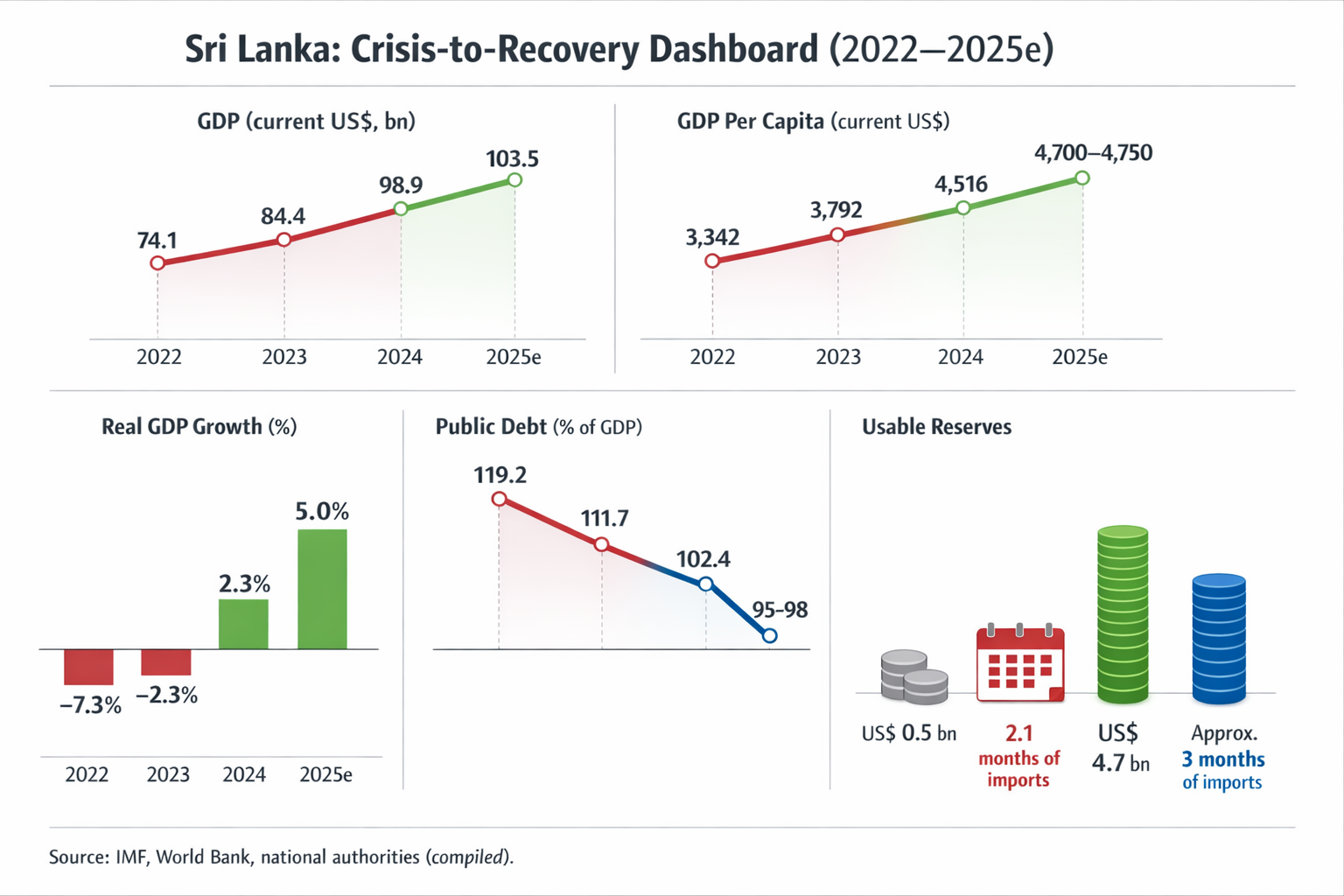

Key indicators track Sri Lanka’s gradual stabilization pathWorld Bank Open Data and the Macro Poverty Outlook show the sharp contraction in 2022 followed by gradual recovery. This path mirrors the global debt buildup problem described in (https://economiclens.org/the-global-debt-clock-is-ticking-why-borrowing-has-no-off-ramp/).

Debt Structure and Creditor Exposure

The Sri Lanka debt crisis was further complicated by creditor diversity. In particular, a large share of external debt consisted of international sovereign bonds held by private investors, while simultaneously bilateral creditors, including China, India, and Paris Club members, formed another major segment. Meanwhile, multilateral lenders accounted for a smaller but senior portion. As a result, this fragmented structure slowed restructuring, since private bondholders required lengthy legal negotiations and bilateral coordination took time. Accordingly, the World Bank notes that creditor fragmentation increases delay risks and raises recovery costs for crisis economies (https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt).

Crisis Timeline and Trigger Stack

The Sri Lanka debt crisis unfolded through a clear sequence. Tax cuts in 2019 weakened revenues. The pandemic hit tourism and remittances in 2020 and 2021. Global commodity and energy prices surged in 2022. Capital inflows reversed as global interest rates rose. Reserves collapsed. Debt service was suspended.

This trigger stack explains why the crisis accelerated quickly. It also shows why emerging economies with similar exposure face elevated risk today.

2. What Caused the Emerging Market Debt Crisis in Sri Lanka

Weak Fiscal Base Turned Debt into a Trap

The Sri Lanka sovereign debt crisis was driven primarily by chronic revenue weakness rather than sudden spending excesses. Over time, persistently low tax collection left the state with limited fiscal capacity, and subsequently pre-pandemic tax cuts reduced fiscal buffers even further. At the same time, spending rigidities persisted, so in practice borrowing gradually replaced revenue as the main financing source. When financing conditions tightened, debt servicing absorbed a rising share of government revenues and as a result adjustment space quickly vanished. Accordingly, the IMF emphasizes that domestic revenue mobilization is the strongest long-term defense against debt distress (https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/taxes-and-revenue-mobilization), and Sri Lanka’s experience clearly confirms this lesson.

Foreign Exchange Crisis in Sri Lanka

The foreign exchange crisis in Sri Lanka transformed fiscal stress into systemic failure. By 2022, usable reserves were nearly exhausted. Essential imports were disrupted. Confidence collapsed.

Currency depreciation followed, intensifying inflation. The World Bank (https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/brief/reserves-and-external-stability) shows that usable reserves, not headline figures, determine crisis resilience. Sri Lanka’s collapse illustrates this vulnerability.

Inflation Crisis in Sri Lanka as a Social Shock

The inflation crisis in Sri Lanka turned a financial breakdown into a social emergency. Inflation surged to nearly 70 percent. Food prices more than doubled between 2021 and 2024. Real wages collapsed. Poverty increased sharply.

World Bank analysis (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/macroeconomics/brief/inflation-and-poverty) confirms that inflation disproportionately harms low-income households. Stabilization did not reverse this damage.

3. IMF Program in Sri Lanka and Stabilization

The IMF program in Sri Lanka restored macro stability. Tax reforms strengthened revenues. Monetary tightening reduced inflation. External financing rebuilt reserves. The primary balance shifted toward consolidation.

The IMF (https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/LKA) notes that stabilization relied on fiscal reform, reserve rebuilding, and restructuring progress. Fiscal tightening alone would not have worked.

Debt Restructuring Progress and Remaining Risks

Debt ratios declined after 2023. Growth recovery and currency appreciation helped. However, debt remains high. Financing needs persist. Legal and bilateral risks remain.

The World Bank (https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt/brief/sovereign-debt-restructuring) highlights that delayed restructuring suppresses investment and prolongs uncertainty. Speed matters as much as relief size.

Post-Default Economic Recovery and Fragility

Growth returned in 2024, led by tourism and services. Manufacturing and investment lagged. Climate disruptions in late 2025 added pressure, according to Reuters (https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/). The OECD (https://www.oecd.org/economy/resilience/) warns that growth without diversification remains fragile.

Political Economy and Reform Durability

The Sri Lanka debt crisis also exposed governance constraints. Fiscal reforms face political resistance. Election cycles threaten consolidation. Public trust remains fragile after inflation shocks.

This political economy constraint explains why emerging economy recoveries often relapse. Reform durability matters as much as reform design.

4. Lessons from the Sri Lanka Debt Crisis for Emerging Economies

Some argue the Sri Lanka debt crisis proves austerity always works. However, evidence shows stabilization succeeded only when fiscal reform, IMF financing, reserve rebuilding, and debt restructuring progressed together. Austerity alone would have deepened social damage without restoring confidence.

Policy Implication Box

Policy implication: The Sri Lanka debt crisis demonstrates that emerging economies must manage debt through a unified framework. Weak revenues force borrowing. Low reserves magnify shocks. Delayed restructuring prolongs uncertainty. Inflation transmits fiscal failure into social instability. Sustainable recovery requires synchronized reform across fiscal systems, external buffers, debt governance, and political institutions. Growth supports adjustment, but it cannot replace these foundations.