The fragmented global economy is no longer an emerging trend. It has become the operating system of the contemporary world economy. Cross-border trade, finance, and supply chains continue to function, but they no longer operate under conditions of universal openness. Instead, economic exchange is increasingly shaped by political alignment, security considerations, and strategic trust.

This transformation is frequently described as deglobalization. Such a characterization is misleading. Globalization has not ended. Rather, the fragmented global economy reflects a redesign of integration rather than its dismantling. Economic connectivity persists, but it is selective, conditional, and increasingly politicized.

Understanding this shift is critical for policymakers. Frameworks designed for an era of universal integration are ill-suited to an environment defined by selective connectivity and strategic risk management. This editorial argues that the fragmented global economy does not represent a failure of globalization, but its new operating logic, shaped by security concerns, geopolitical alignment, and long-term risk mitigation.

1. The Fragmented Global Economy Has Replaced Universal Globalization

For several decades, globalization followed a relatively clear organizing principle. Efficiency dominated decision-making. Firms optimized costs, extended supply chains across continents, and relied on predictable trade rules. Governments largely played a supporting role.

That assumption no longer holds in the fragmented global economy. Global trade volumes remain elevated, as confirmed by World Trade Organization data (https://www.wto.org). However, capital flows and production networks are now increasingly driven by geopolitical risk, regulatory uncertainty, and security considerations rather than price signals alone.

These developments indicate that the fragmented global economy represents reorganization rather than collapse. Trade continues, but integration is no longer neutral or universally accessible. This dynamic is examined in detail in https://economiclens.org/the-future-of-international-trade-how-economic-blocs-are-reshaping-the-global-economy/, which shows how economic blocs are reshaping global commerce within a fragmented global economy.

2. Bloc-Based Globalization Is Rewriting Trade Rules

In the fragmented global economy, economic blocs are increasingly replacing multilateral institutions as the primary organizing force of trade. Cross-border flows are becoming concentrated within political and strategic alliances.

Asian economies are deepening intra-regional trade. European states are reinforcing internal sourcing and regulatory alignment. North America is prioritizing near-shoring and friend-shoring strategies. As a result, exposure to politically distant partners is now viewed as a structural vulnerability rather than a diversification benefit.

The OECD documents a sharp increase in export controls, industrial subsidies, and trade interventions since 2019 (https://www.oecd.org). Market access in this divided global economy is therefore shaped less by efficiency and more by geopolitical alignment.

Recent developments reinforce this pattern. Red Sea shipping disruptions increased freight and insurance costs. United States–China semiconductor controls tightened access to advanced technologies. BRICS economies expanded the use of local currency settlement mechanisms. These trends are further analyzed in https://economiclens.org/brics-expansion-de-dollarization-and-the-shift-in-global-finance/, which shows how bloc-based trade and financial arrangements increasingly define a multipolar economic system.

3. Supply Chain Fragmentation and the Rise of Sovereignty

Supply chains provide the clearest illustration of the fragmented global economy. Governments are increasingly prioritizing resilience and security over cost minimization.

Sectors such as semiconductors, energy technologies, pharmaceuticals, and critical minerals are now treated as strategic assets rather than conventional goods. National security considerations increasingly determine sourcing decisions and investment approvals within the fragmented global economy.

This shift is examined in https://economiclens.org/supply-chain-sovereignty-the-new-realignment-in-global-trade/, which explains why governments are willing to accept higher costs in exchange for reduced strategic exposure. The International Monetary Fund has cautioned that aggressive reshoring may raise inflationary pressures and weaken productivity growth over time (https://www.imf.org). Nevertheless, political risk now consistently outweighs efficiency gains in policy decision-making.

4. Strategic Trade Realignment and Permanent Sanctions

Sanctions and trade controls are no longer temporary instruments. They have become enduring features of the fragmented global economy.

Export restrictions, investment screening mechanisms, and technology bans increasingly shape long-term industrial outcomes. Firms now operate in markets where political constraints are structural rather than exceptional. This transformation is explored in https://economiclens.org/economic-cold-war-2025-the-battle-for-supply-chains-and-global-power/, which shows how supply chains and technology access have become central arenas of geopolitical competition.

The World Bank notes that persistent trade policy uncertainty is dampening investment and growth (https://www.worldbank.org). Consequently, firms must manage geopolitical alignment alongside conventional market strategy in the fragmented global economy.

5. Fragmentation Without Collapse in the Global Economy

Despite growing concern, the fragmented global economy does not indicate systemic breakdown. Trade continues, capital flows persist, and technology diffusion remains ongoing, although unevenly distributed.

What has fundamentally changed is the architecture of integration. The Bank for International Settlements confirms that global finance is fragmenting into parallel systems rather than collapsing outright (https://www.bis.org). Connectivity remains, but it is conditional and increasingly segmented. The BIS Quarterly Review further highlights how fragmentation is generating parallel financial and trade systems instead of triggering global retreat (https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf).

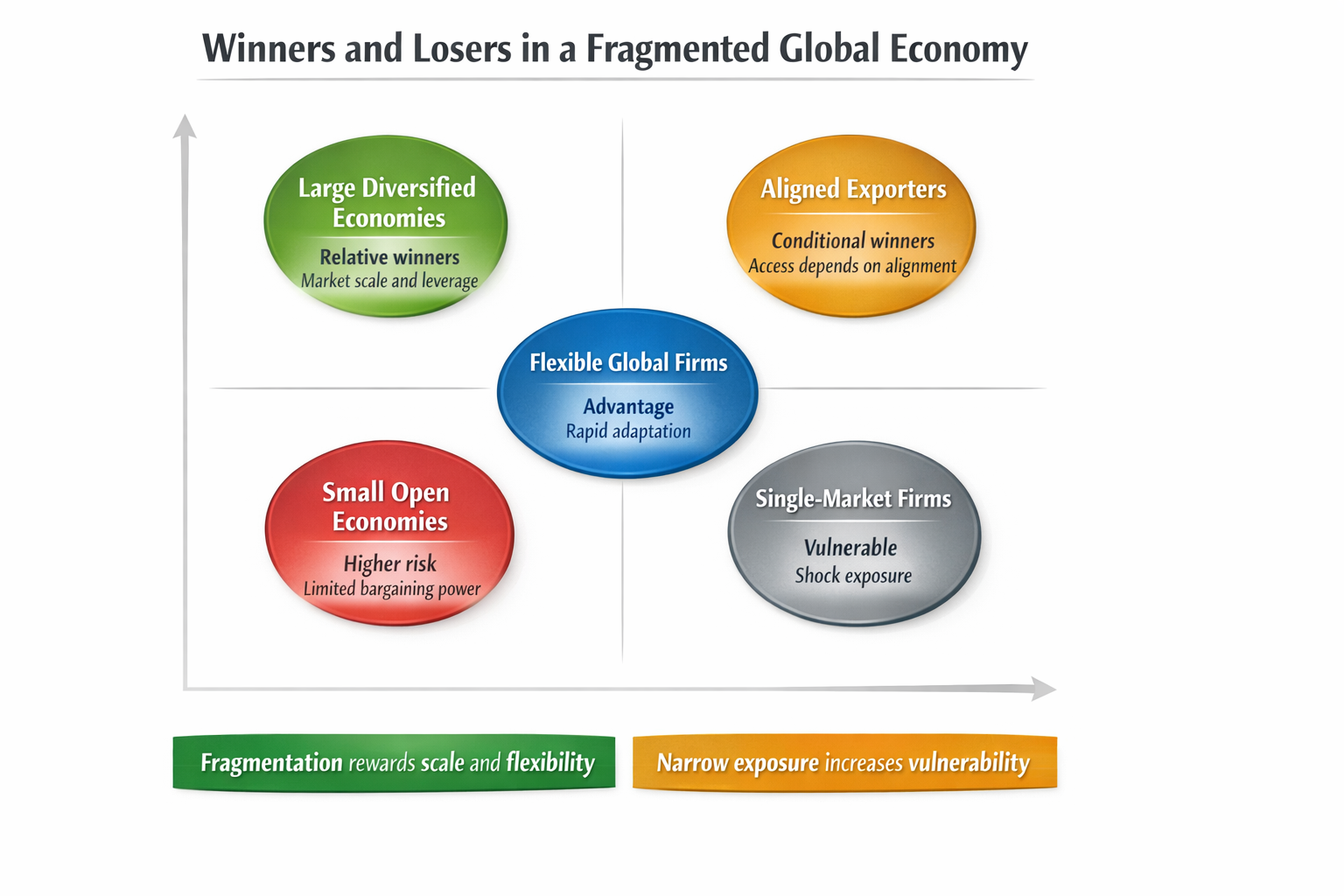

6. Winners and Losers in a Fragmented Global Economy

Fragmentation reshapes outcomes unevenly across the global economy. Large, diversified economies and flexible global firms tend to adapt more effectively, while small open economies and single-market firms face heightened vulnerability.

For policymakers, the central challenge is no longer maximizing openness. It is managing selective integration in a manner that limits inflationary pressures and systemic instability within the fragmented global economy.

Editorial Verdict

The fragmented global economy is no longer a transitional phase. It is the defining condition of the modern world economy.

Globalization has not ended. It has been rewritten. Efficiency now competes with resilience. Openness is conditional. Alignment matters.

Framing this shift as deglobalization misunderstands the moment. The world is not retreating from globalization. It is reorganizing it. In a divided global economy, success will depend on adaptation, alignment, and strategic realism rather than reliance on outdated models of universal integration.

If you want, I can next tighten this further for journal submission, adapt it into an executive policy brief, or extract figure-ready analytical summaries for tables and visual explainers.