Food inflation in emerging economies remains stubbornly high despite easing global inflation. Using cross-country data and IMF and FAO insights, this analysis explains why food prices remain sticky, how this worsens cost of living pressures, and why monetary policy alone cannot resolve food-driven inflation stress.

Introduction

Food inflation in emerging economies remains one of the most persistent sources of economic stress in 2025–2026. Although global headline inflation has declined sharply, food prices continue to rise faster than overall inflation across many developing countries.

As a result, inflation relief feels incomplete for millions of households. Food accounts for a large share of consumption in emerging economies, so elevated food prices dominate lived inflation. Consequently, falling headline inflation does not translate into meaningful cost of living relief.

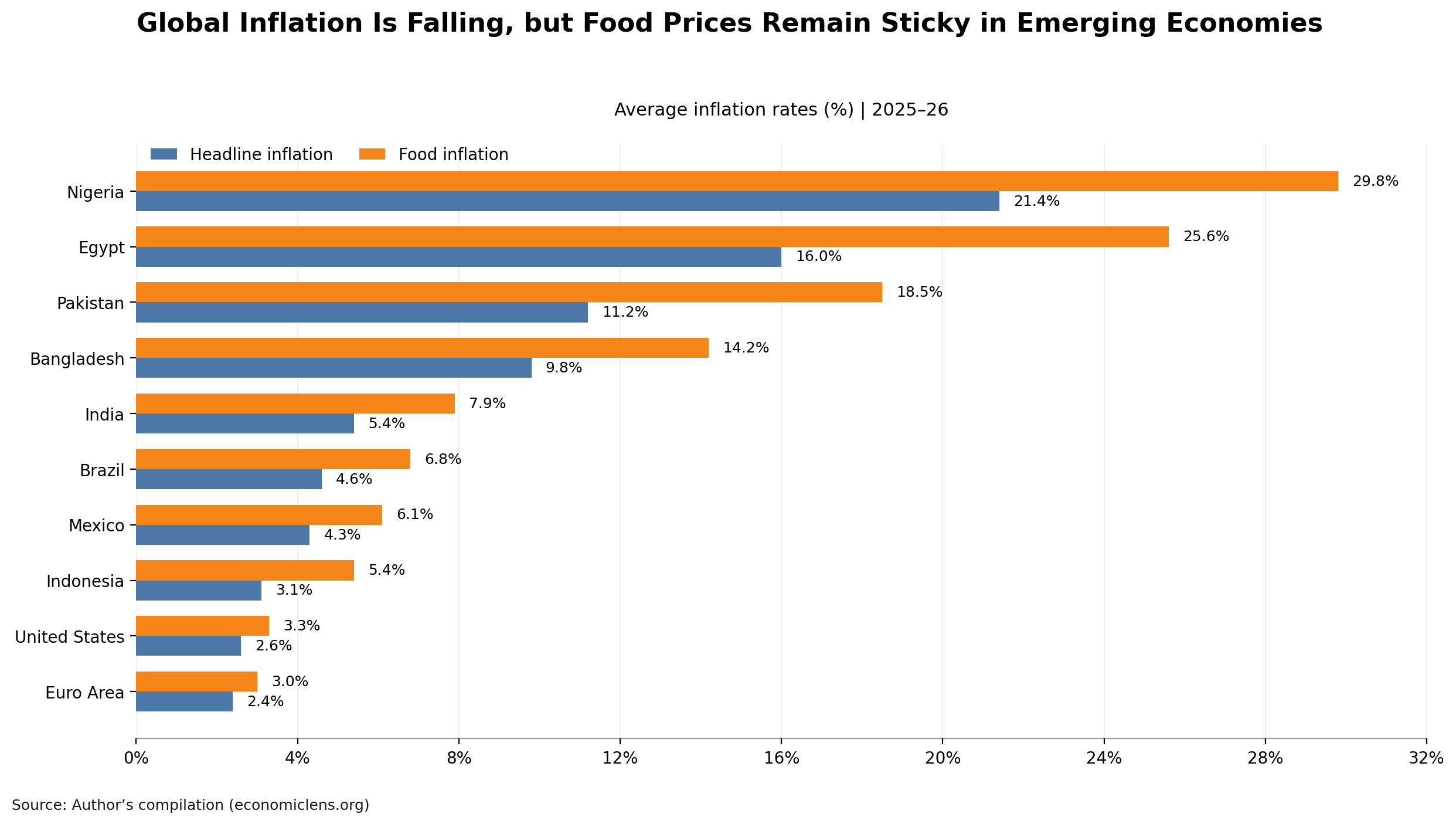

This divergence is visible across regions. The chart shows that food inflation consistently exceeds headline inflation in most emerging economies, while advanced economies experience much narrower gaps. This pattern aligns with broader inflation persistence dynamics discussed in Inflation persistence and the middle-class squeeze (https://economiclens.org/inflation-persistence-and-the-middle-class-squeeze-why-prices-are-not-falling-fast-enough/).

Food Inflation in Emerging Economies: What the Data Reveals

Food inflation in emerging economies remains significantly higher than headline inflation across multiple regions. Nigeria, Egypt, Pakistan, and Bangladesh display the most pronounced gaps between food and headline inflation.

In Nigeria, headline inflation averages slightly above 21 percent. However, food inflation approaches 30 percent. Similarly, Egypt records food inflation far above its headline rate, reflecting sustained pressure on essential goods. Pakistan and Bangladesh follow the same pattern, although at lower absolute levels.

By contrast, advanced economies such as the United States and the euro area show limited divergence. Food inflation there remains only marginally above headline inflation. This contrast explains why inflation perceptions differ sharply between emerging and advanced economies.

Why Sticky Food Prices Persist Despite Falling Inflation

Sticky food prices reflect structural constraints rather than excess demand. Unlike manufactured goods, food production depends heavily on climate conditions, logistics, and imported inputs.

First, climate volatility continues to disrupt agricultural output. Weather shocks affect emerging economies more severely because farming systems remain less diversified and less mechanized (https://www.fao.org).

Second, currency depreciation sustains food inflation. Many emerging economies import food and agricultural inputs priced in US dollars. Even moderate exchange rate weakness raises domestic food prices.

Third, food prices did not merely spike after 2020, they reset at a higher level. Global supply chain disruptions, fertilizer shocks, and export restrictions created a new price floor, as analyzed in Global food inflation crisis: why food prices reset higher after 2020 (https://economiclens.org/global-food-inflation-crisis-why-food-prices-reset-higher-after-2020/).

Consequently, food producers face ongoing cost pressures that delay price normalization even as headline inflation falls.

Emerging Market Food Inflation and Household Welfare

Emerging market food inflation has direct and unequal welfare effects. Food represents a far larger share of household spending in developing economies than in advanced ones.

In Nigeria, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, food often exceeds 40 percent of household consumption. Therefore, even modest increases in food prices sharply reduce real incomes. As a result, households experience inflation more intensely than headline indicators suggest.

This explains persistent public dissatisfaction during disinflation phases. Inflation statistics improve, yet household budgets remain under pressure. Consequently, governments face political strain despite macroeconomic stabilization.

Food inflation thus functions as a social stress amplifier, not merely a price index component.

Limits of Monetary Policy in Addressing Food Inflation

Monetary policy has limited effectiveness against food inflation in emerging economies. Interest rate hikes suppress demand-driven inflation, but they cannot resolve supply-side shocks.

Moreover, tighter policy can indirectly worsen food inflation. Higher borrowing costs raise financing expenses for farmers and food distributors. Additionally, fiscal tightening often reduces food subsidies.

As a result, central banks face a difficult trade-off. Tight policy stabilizes currencies but leaves food prices elevated. Loose policy risks depreciation, which increases imported food costs (https://www.imf.org).

This constraint explains why food inflation lags headline disinflation across emerging markets.

Policy Responses Beyond Interest Rates

Reducing food inflation in emerging economies requires supply-side and institutional reforms. Monetary tightening alone cannot deliver sustained food price stability.

First, agricultural productivity investment is essential. Irrigation, storage, and transport infrastructure reduce post-harvest losses and price volatility over time (https://www.worldbank.org).

Second, targeted food subsidies are more effective than blanket price controls. Well-designed programs protect vulnerable households without distorting markets.

Third, external financing buffers matter. Stable foreign exchange reserves help limit currency-driven food inflation shocks (https://unctad.org).

Without these measures, food inflation will remain sticky even during global disinflation cycles.

What Food Inflation in Emerging Economies Means Going Forward

Food inflation in emerging economies is likely to ease gradually rather than collapse. Global disinflation provides relief, but structural constraints persist.

Emerging economies will continue to experience higher inflation volatility than advanced peers. However, this outcome reflects economic structure rather than policy failure.

The primary risk lies in misinterpreting inflation progress. Headline disinflation can mask persistent food price stress. Therefore, policymakers and analysts must focus on inflation composition, not just averages.

Ultimately, inflation may be falling globally. Yet for many households, food prices still define economic reality.