AI and job displacement is transforming the future of work by accelerating automation, exaggerating productivity gains, and deepening wage polarization. As artificial intelligence spreads across labor markets, middle-wage jobs decline, labor’s income share falls, and economic adjustment costs shift toward workers rather than firms.

Introduction: AI and Job Displacement

AI and job displacement has emerged as one of the most consequential economic challenges of the digital era. Governments and corporations frequently present artificial intelligence as a neutral engine of efficiency and growth. However, workers increasingly experience insecurity, fragmentation, and declining bargaining power. As a result, labor markets face structural disruption rather than smooth technological adjustment. AI now reshapes not only how work is performed, but also how income, risk, and power are distributed across modern economies.

AI and Job Displacement in Modern Labor Markets

AI and job displacement refers to the replacement or restructuring of human labor through algorithmic systems across a widening range of tasks. Unlike earlier technological waves that primarily affected manual labor, AI increasingly targets routine cognitive, clerical, and decision-based work. Consequently, displacement now extends into white-collar and service occupations that were previously considered resilient.

Moreover, firms adopt AI primarily to reduce labor costs and tighten operational control. They rarely deploy automation to expand output or employment capacity. Therefore, displaced workers struggle to secure equivalent roles with comparable wages and stability. This pattern produces persistent employment gaps rather than short-lived adjustment friction.

In addition, AI adoption concentrates within large firms that possess capital, data, and digital infrastructure. Smaller firms lag behind, which limits job creation and competitive diffusion. As a result, labor market churn rises while job quality deteriorates. Sectoral exposure also varies, as detailed in EconomicLens’ analysis of sector-specific risks (https://economiclens.org/how-will-ai-disrupt-jobs-in-2026-sectoral-shifts-and-labor-market-risk/). AI and job displacement therefore reflects deep structural change rather than temporary disruption.

Automation, Reskilling, and the Limits of Adjustment

Policy responses to AI and job displacement frequently emphasize reskilling and lifelong learning. Governments assume displaced workers can transition into new digital roles. However, this assumption ignores structural and demographic constraints. Not all workers possess the aptitude, resources, or time to retrain for advanced technical occupations.

Furthermore, training systems adapt slowly to technological change. By the time curricula update, job requirements often shift again. Consequently, reskilling efforts lag behind automation cycles. Many workers complete training programs only to face renewed displacement or downgraded employment.

Additionally, AI-driven sectors generate fewer jobs per unit of output than earlier industrial expansions. High productivity reduces labor demand even when output grows. As a result, reskilling improves individual employability but fails to resolve aggregate job shortages. These dynamics are explored further in EconomicLens’ broader assessment of automation and inequality (https://economiclens.org/ai-and-automation-navigating-job-displacement-economic-inequality-in-2026/). AI and job displacement therefore persists despite continuous retraining initiatives.

Productivity Myths Surrounding Job Displacement

Advocates of automation argue that AI and job displacement will be offset by strong productivity gains. In theory, efficiency improvements should raise output, wages, and living standards. Yet empirical evidence increasingly contradicts this expectation. Productivity growth across advanced economies has remained weak despite rapid AI diffusion (https://www.oecd.org).

This contradiction reflects how firms deploy AI in practice. Automation often substitutes labor without expanding production capacity. Firms prioritize cost compression, workforce reduction, and margin protection rather than innovation-led expansion. Consequently, productivity gains remain firm-specific and fail to diffuse across the broader economy.

Moreover, productivity metrics often overstate real value creation. AI reallocates tasks and intensifies labor without improving output quality or aggregate demand. As a result, headline efficiency masks stagnant incomes and weak wage growth. These dynamics align closely with the productivity paradox examined in detail by EconomicLens (https://economiclens.org/ai-productivity-paradox-why-automation-is-not-boosting-growth/). The productivity promise attached to AI and job displacement therefore remains largely unfulfilled.

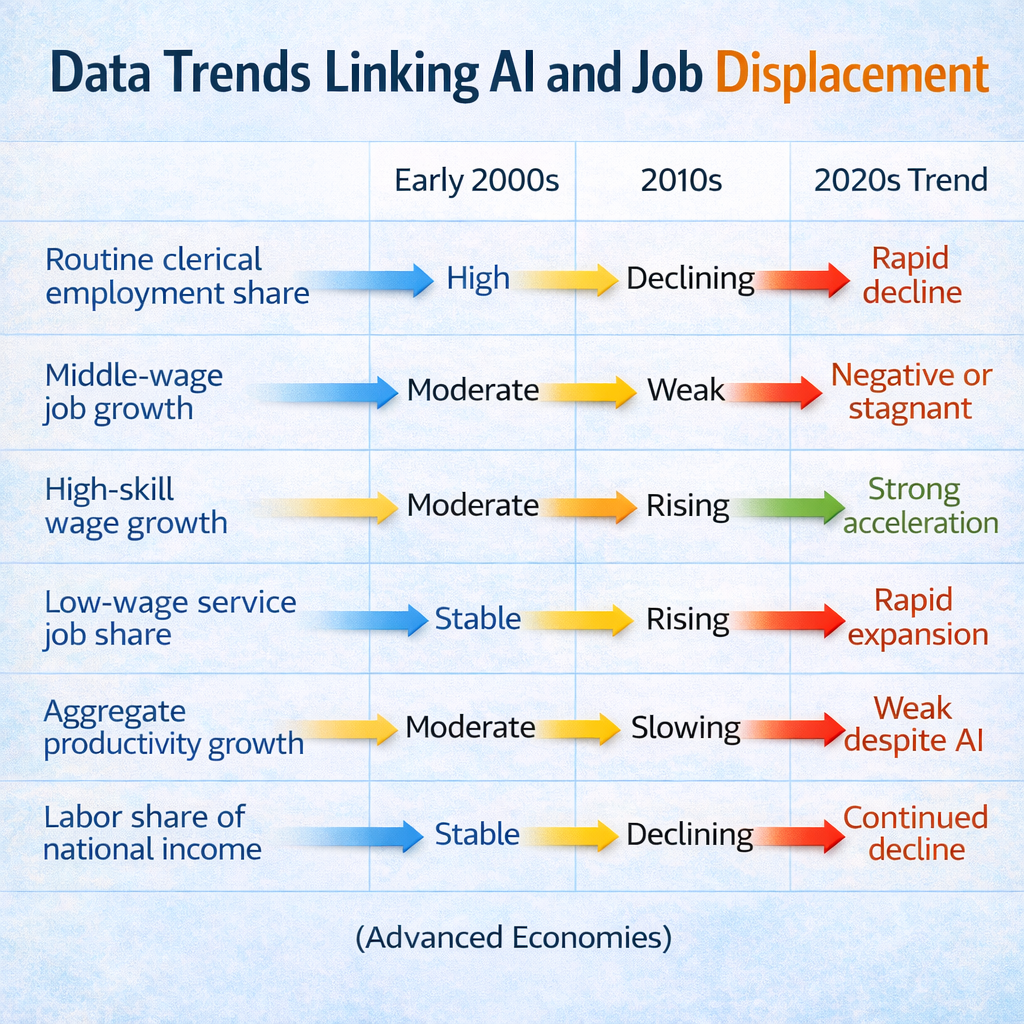

Data Trends Linking AI and Labor Displacement

The table below summarizes long-run labor market trends in advanced economies, interpreted through a 2025 AI-era lens. These patterns align with findings from the OECD, IMF, and ILO, which emphasize task transformation, wage polarization, and declining labor income shares rather than immediate mass unemployment (https://www.ilo.org).

As AI adoption accelerates, job displacement concentrates in routine and middle-wage roles, while wage gains accrue at the top. Meanwhile, productivity growth fails to translate into broad income gains. This pattern reinforces the structural nature of AI & job displacement, rather than supporting a temporary adjustment narrative.

Wage Polarization Driven by Artificial Inteligence

Wage polarization represents a central outcome of AI & job displacement. High-skill professionals who design, manage, or complement AI systems capture rising incomes. Meanwhile, middle-wage clerical and administrative roles shrink rapidly.

At the same time, low-wage service employment expands. These jobs often lack stability, benefits, and bargaining power. Therefore, employment growth concentrates at the bottom of the wage distribution. This hollowing of the middle class weakens consumption, social mobility, and long-term growth prospects.

AI reinforces this divide by favoring capital ownership and elite skills. Routine labor faces substitution, while strategic oversight remains scarce. Consequently, inequality widens even when headline employment figures appear stable. These dynamics are particularly severe for younger workers entering the labor market, as documented in EconomicLens’ analysis of youth unemployment and AI disruption (https://economiclens.org/global-youth-unemployment-2025-ai-disruption-skills-gaps-the-gen-z-jobs-crunch/). AI and job displacement thus reshapes income distribution across generations as well as occupations.

Power Shifts Between Capital and Labor

Beyond wages, AI and job displacement alters workplace power relations. Employers gain algorithmic monitoring, predictive scheduling, and performance scoring tools. Workers face constant evaluation, often without transparency or effective recourse.

Additionally, AI enables just-in-time task allocation and flexible staffing. While this flexibility benefits firms, it destabilizes workers. As a result, labor loses predictability and autonomy. Employment becomes fragmented and increasingly contingent.

Platform-based work further weakens collective bargaining. Algorithms replace human negotiation and obscure wage determination. Consequently, power concentrates among technology owners and shareholders. AI and job displacement therefore strengthens capital dominance within labor relations (https://www.bis.org).

Policy Illusions and Adjustment Costs

Policy debates surrounding AI and job displacement often prioritize innovation incentives and digital infrastructure. Governments assume that economic growth will absorb displaced workers. However, persistent labor market stress challenges this assumption.

Structural unemployment remains visible even in expanding economies. Many displaced workers accept lower-quality jobs or exit the labor force altogether. Meanwhile, social safety nets remain inadequate. Income volatility increases household insecurity and political tension.

Furthermore, adjustment costs fall disproportionately on workers. Firms internalize efficiency gains, while society absorbs disruption. Without stronger labor institutions, AI and job displacement becomes a source of economic and political instability (https://www.unctad.org).

Conclusion

AI and job displacement is not a neutral consequence of technological progress. It reflects policy choices about ownership, governance, and distribution. Job losses, weak productivity spillovers, and wage polarization expose deep structural imbalances.

Ultimately, the future of work depends less on AI capability and more on institutional design. Without reform, automation will deepen inequality and insecurity. Therefore, addressing AI and job displacement requires rethinking how economies distribute risk, reward, and power in the digital era.