The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis represents a multi-layered breakdown of governance, economic stability, and social cohesion. This policy note examines how security disruptions, poverty, corruption, and youth vulnerability reinforce institutional decay, weaken public services, and strain provincial capacity, while outlining pathways for stabilization and reform.

Introduction

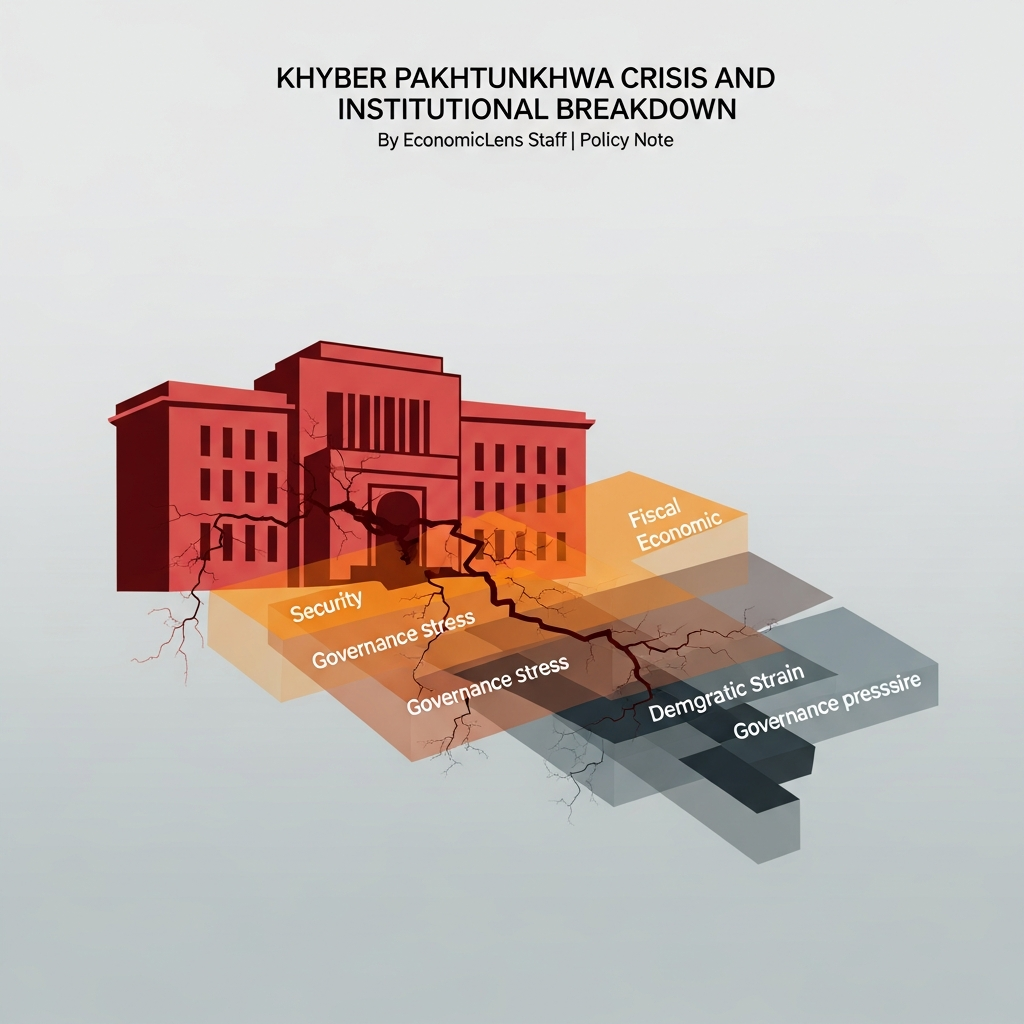

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis has evolved into a systemic governance failure rather than a series of disconnected shocks. Over the past decade, recurring security disruptions, declining institutional capacity, fiscal stress, and demographic pressure have interacted in mutually reinforcing ways. What initially appeared as isolated administrative or security challenges has matured into a province-wide crisis of state effectiveness.

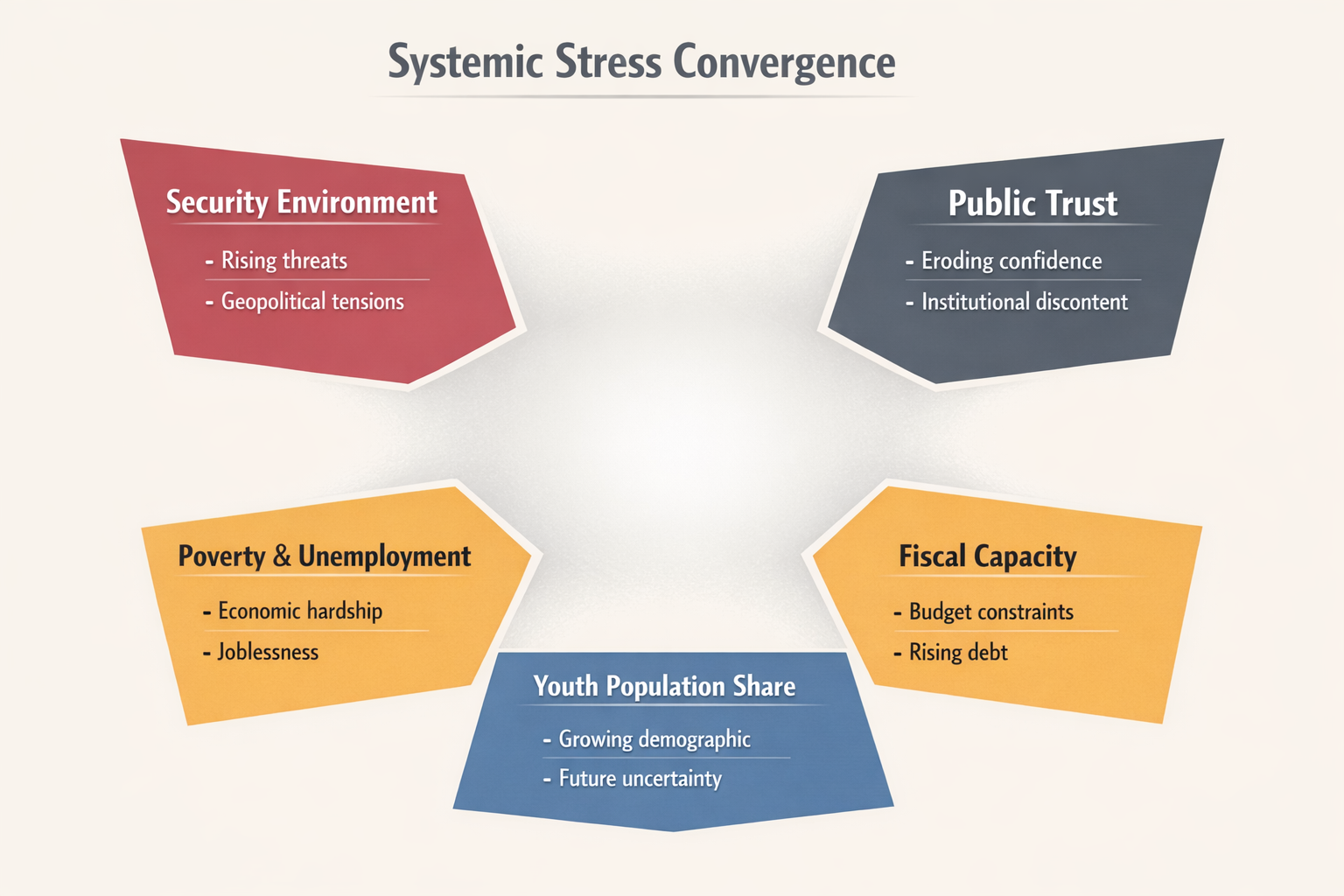

The crisis is shaped by a fragile security environment, disrupted cross-border economic activity, entrenched poverty, and rising youth vulnerability. These pressures have steadily eroded state capacity, weakened public service delivery, and reduced public trust in provincial institutions. Governance failures now transmit directly into economic distress and social fragmentation. This policy note examines how governance decay, economic strain, and social stress interact in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, why the crisis has deepened over time, and which policy pathways are necessary for institutional and economic stabilization.

1. KP Governance Crisis and Institutional Decay

The governance dimension of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis lies at the core of the province’s broader breakdown. Persistent security threats, weakened law enforcement capacity, and declining administrative effectiveness have undermined state authority and policy coherence. Border disruptions and instability along adjoining regions have further strained coordination between civilian administrations and security institutions.

As detailed in EconomicLens’ analysis of the KP governance crisis, security turmoil and border disruptions have constrained mobility, disrupted economic networks, and weakened inter-agency coordination, thereby accelerating institutional decay

https://economiclens.org/kp-governance-crisis-security-turmoil-border-disruptions-and-institutional-decay/

Governance in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has increasingly become reactive rather than strategic. Policy responses are crisis-driven, short-term, and weakly monitored. Accountability mechanisms remain fragile, allowing fiscal leakages and administrative inefficiencies to persist. This erosion of institutional credibility distorts development priorities, undermines fiscal discipline, and reduces the effectiveness of public policy across sectors.

2. KP Economic Crisis Within the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Crisis

The economic dimension of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis reflects both structural weaknesses and prolonged governance failure. Poverty remains widespread, private investment is subdued, and employment creation has consistently lagged behind population growth. Weak oversight and entrenched corruption continue to distort public spending and undermine development outcomes.

EconomicLens’ assessment of the KP economic crisis demonstrates how revenue shortfalls, financial strain, and governance leakages have reduced the province’s capacity to fund essential services and development priorities

https://economiclens.org/kp-economic-crisis-poverty-corruption-pressures-and-financial-strain/

Limited fiscal autonomy and rising recurrent expenditures have further narrowed policy space. As a result, the economic crisis reinforces governance fragility while deepening social stress. This feedback loop locks the province into a low-capacity, low-growth equilibrium that is increasingly difficult to reverse without structural reform.

3. KP Social Crisis and Human Stress

The social dimension of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis is driven by rapid population growth, a disproportionately large youth cohort, and weak human capital outcomes. Education and health systems remain under sustained strain, while labor markets fail to absorb new entrants at sufficient scale.

As highlighted in EconomicLens’ analysis of KP’s social crisis, demographic pressure and youth vulnerability are reaching critical thresholds, with long-term implications for social cohesion and stability

https://economiclens.org/kp-social-crisis-demographic-stress-youth-vulnerability-and-human-collapse/

Without inclusive growth and effective service delivery, social stress increasingly feeds back into governance and security challenges. The social crisis is therefore not a secondary consequence of economic weakness. It is an accelerating force within the broader Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis.

4. Crisis Nexus: Why the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Crisis Persists

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis functions as a self-reinforcing system. Weak governance undermines economic performance. Economic distress deepens social vulnerability. Social stress, in turn, fuels instability and further weakens governance capacity.

This crisis nexus explains why fragmented interventions have repeatedly failed. Addressing poverty without institutional reform produces limited and temporary gains. Improving security without expanding economic opportunity fails to restore public trust. Social protection without fiscal sustainability remains fragile and politically contested.

Policy Constraints

Policy responses to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis operate under binding structural constraints that limit both the scope and effectiveness of reform. Fiscal space is narrow due to weak revenue mobilization, rising recurrent expenditures, and dependence on federal transfers, leaving limited room for countercyclical or development-oriented spending. Administrative capacity is uneven across districts, with acute shortages in technical expertise, monitoring capability, and implementation depth, particularly in conflict-affected and border regions.

Security imperatives further constrain policy choice. Persistent volatility diverts administrative attention and fiscal resources away from long-term development planning toward short-term stabilization. This crowds out institutional reform, delays project execution, and reinforces reactive governance. At the same time, coordination between provincial and federal authorities remains inconsistent, complicating policy alignment in areas such as security management, fiscal transfers, and border administration.

Taken together, these constraints mean that isolated or sector-specific reforms are unlikely to succeed. Without addressing fiscal, administrative, and coordination limitations simultaneously, policy interventions risk becoming fragmented, underfunded, and politically unsustainable.

5. Policy Pathways for Stabilization

Stabilizing the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis requires a coordinated reform strategy that addresses governance failure, economic stagnation, and social vulnerability simultaneously. Sequencing matters, but isolation does not work. The following policy pathways outline the core pillars required for durable stabilization.

1. Restoring Governance Credibility and Institutional Capacity

Governance reform must serve as the primary anchor of stabilization. Without credible institutions, economic initiatives and social programs remain fragmented, poorly implemented, and politically fragile. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, prolonged crisis-driven governance has weakened accountability, distorted policy priorities, and eroded public trust.

International evidence from fragile and conflict-affected regions shows that weak institutions amplify insecurity, fiscal leakage, and long-term instability, a pattern highlighted in World Bank research on governance and fragility (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/governance). Restoring governance credibility therefore requires strengthening oversight mechanisms, improving administrative professionalism, and enforcing transparency in procurement and public finance. Governance reform is not an auxiliary objective. It is the institutional foundation for all other stabilization efforts.

2. Reviving Economic Activity and Fiscal Effectiveness

Economic recovery is necessary to give governance reform legitimacy and durability. The economic dimension of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis cannot be resolved through isolated projects, ad hoc relief, or short-term stimulus. Structural weaknesses in investment, employment generation, and revenue mobilization continue to constrain growth and reinforce poverty and fiscal stress.

Global experience shows that regions facing institutional fragility require targeted local economic development rather than broad-based stimulus, as emphasized in World Bank analysis on jobs and private sector recovery in fragile economies (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/jobsanddevelopment). Targeted support for local value chains, small and medium enterprises, and border-adjacent commercial activity can revive livelihoods and reduce dependence on transfers, provided spending efficiency and anti-corruption enforcement improve in parallel.

3. Addressing Youth Vulnerability and Human Capital Stress

Youth vulnerability represents the most time-sensitive risk within the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis. The province’s demographic structure means that failure to integrate young people into productive education, skills development, and labor markets will amplify instability and undermine long-term recovery. Weak human capital outcomes increasingly feed back into governance and security pressures.

International research consistently links youth exclusion to social instability and conflict risk, a relationship extensively documented in UNDP work on youth, employment, and social cohesion (https://www.undp.org/youth). Education reform must therefore prioritize quality and relevance, while skills development programs must align with local labor demand. Youth inclusion is not merely a social policy concern. It is a governance and stability imperative.

4. Aligning Security Policy With Economic and Institutional Recovery

Persistent insecurity and unpredictable border disruptions continue to undermine reform efforts by discouraging investment, restricting mobility, and weakening administrative authority. When security policy operates independently of economic and governance objectives, institutional recovery becomes unattainable.

Comparative evidence from conflict-affected regions shows that security-first approaches fail when not paired with economic normalization and civilian governance, a conclusion reinforced by OECD analysis on security and development policy coherence (https://www.oecd.org/dac/conflict-fragility-resilience/). Stabilization therefore requires closer coordination between civilian administration and security institutions, predictable border management frameworks, and normalization of economic activity in affected regions.

5. Ensuring Policy Integration and Parallel Implementation

The central lesson of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis is that fragmented reforms fail. Governance reform without economic improvement loses legitimacy. Economic initiatives without institutional discipline leak resources. Social programs without fiscal sustainability collapse under pressure.

Global policy experience shows that successful stabilization in fragile regions depends on integrated reform frameworks rather than sectoral silos, as emphasized in IMF work on fragile and conflict-affected states (https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/Fragile-States). Effective stabilization therefore requires governance credibility, economic revival, social inclusion, and security alignment to move in parallel, supported by consistent political commitment and intergovernmental coordination

Risks and Trade-offs

Reform in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa carries significant political, fiscal, and administrative risks. Governance reform may face resistance from entrenched interests, while fiscal consolidation and anti-corruption enforcement can generate short-term political costs. Security realignment and administrative restructuring may also strain already limited institutional capacity. These risks, however, are largely front-loaded.

By contrast, continued delay compounds structural vulnerabilities. Prolonged crisis management entrenches institutional decay, deepens economic stagnation, and accelerates social fragmentation, particularly among youth. The central trade-off is therefore not between reform and stability, but between coordinated reform with transitional costs and perpetual crisis management with rising long-term instability.

Conclusion

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa crisis is systemic and mutually reinforcing. Governance failure, economic distress, and social vulnerability cannot be addressed in isolation. Fragmented responses have repeatedly failed to reverse decline.

Stabilization requires an integrated strategy that restores governance credibility, expands economic opportunity, and addresses demographic pressure simultaneously. When institutional reform, fiscal sustainability, and social inclusion move together, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa can transition from reactive crisis management toward durable recovery.

1 thought on “Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Crisis and Institutional Breakdown”

Hey there! I know this is kinda off topic however , I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in exchanging links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My site addresses a lot of the same topics as yours and I believe we could greatly benefit from each other. If you happen to be interested feel free to shoot me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Wonderful blog by the way!