This blog analyzes Pakistan’s economic instability by tracing debt pressures, political volatility, policy inconsistency, industrial stagnation, and governance weaknesses across successive governments. It explains how structural flaws—not single tenures—created today’s crisis and outlines reforms needed for long-term stability.

Introduction

Pakistan economic instability reflects decades of accumulated structural weaknesses—spanning fiscal mismanagement, political volatility, industrial stagnation, governance fragility, and chronic policy inconsistency. Economists emphasize that Pakistan’s crisis is not the outcome of one tenure or one leader; it is the sum of multiple governments’ decisions since 2013: PML-N (2013–2018), PTI (2018–2022), PDM (2022–2023), the caretaker setup (2023–2024), and the current government (2024–present). Each inherited deeper vulnerabilities and left behind unresolved challenges.

As political transitions accelerated and IMF programs repeatedly broke and restarted, Pakistan’s economic reform cycles shortened dramatically. The result is a nation trapped in recurring stabilization attempts without structural transformation. This EconomicLens report uses a detailed Trio Section Structure—context, expert insight, published analysis, data table, interpretation, and hook—to reveal the true drivers of Pakistan’s macroeconomic fragility.

1. Debt Overhang: The Structural Weight Pulling Pakistan Down

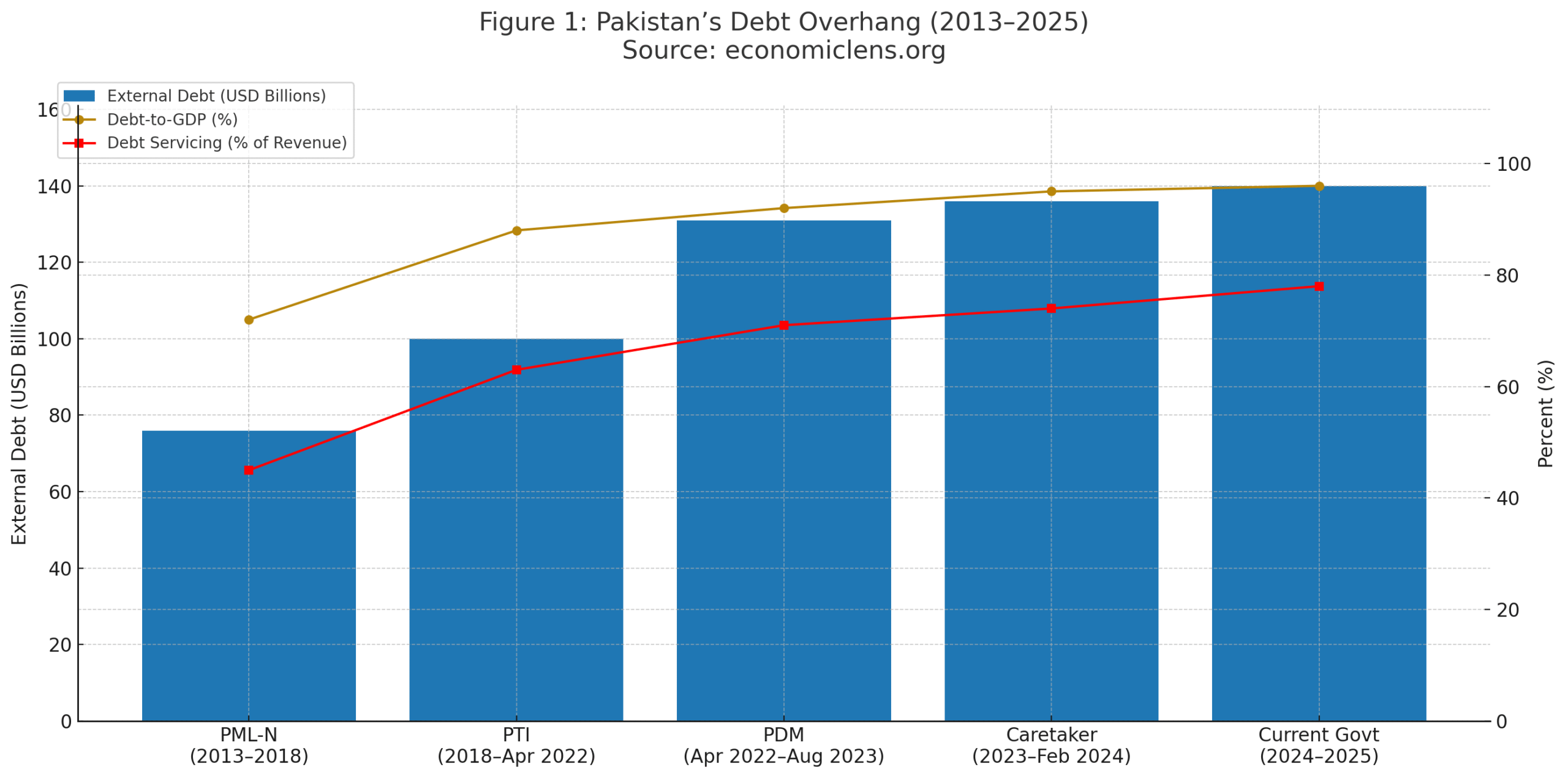

Pakistan’s debt overhang is the single greatest contributor to long-term economic fragility. Over the past decade, debt has risen due to external borrowing, currency depreciation, circular debt, energy subsidies, and IMF delays. Every government contributed to the build-up, but for different reasons—ranging from aggressive borrowing to mismanaged currency shocks.

Former SBP Governor Dr. Ishrat Husain warns: “Pakistan is now borrowing primarily to service past borrowing. This is a classic signature of a country caught in a debt trap.”

The IMF 2024 Debt Sustainability Analysis reports that Pakistan’s annual debt servicing now absorbs more than 71% of federal revenues—one of the highest ratios in the world.

The figure shows an unbroken upward trend in debt from 2013 to 2025. PML-N drove borrowing for energy and CPEC; PTI’s currency crash inflated debt; PDM’s IMF delays worsened servicing costs; the caretaker period saw heavy adjustments; and the current government is suffocating under repayments.

“A nation that spends more on its past than its future can never chart a prosperous path forward.”

2. Political Instability: A Nation Without Continuity

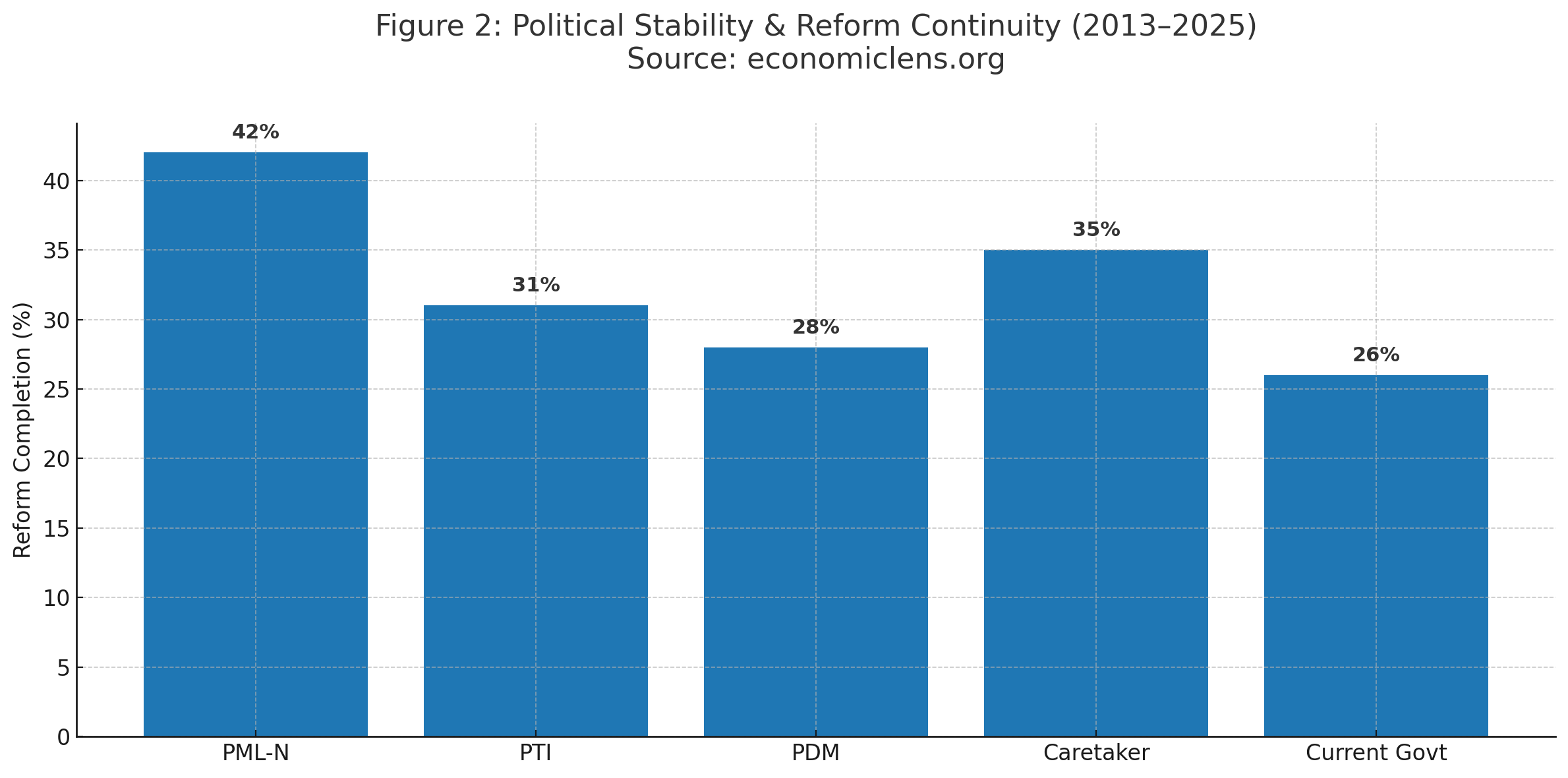

Political instability undermines reform by disrupting continuity, weakening institutions, and shortening policy horizons. Pakistan has experienced intense volatility across all governments since 2013—judicial confrontations, civil–military tensions, coalition fragility, and administrative turnover.

Political scientist Dr. Ayesha Siddiqa states: “Reform cannot survive in a system where politics resets every few months. Instability is a tax on every institution.”

According to the World Governance Indicators 2024, Pakistan ranks in the bottom decile globally for political stability—directly correlated with lower FDI, lower reform continuity, and higher risk premiums.

The figure indicates no administration provided the political stability necessary for long-term reform. PTI faced severe institutional rupture, PDM intense political volatility, the caretaker regime administrative neutrality but harsh IMF conditions, and the current government coalition constraints.

“Economies thrive on continuity—without it, progress before crisis becomes crisis before progress.”

3. Policy Inconsistency: The Reform That Never Stays

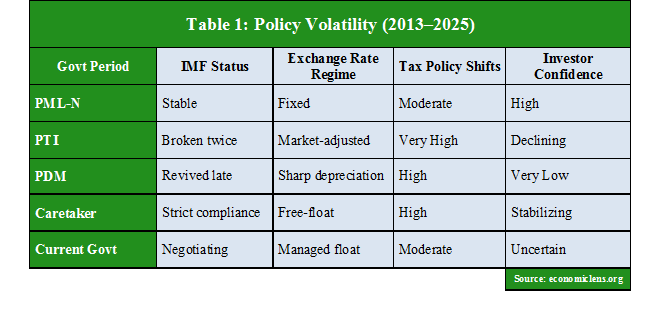

Policy inconsistency—frequent tax changes, shifting energy policies, fluctuating exchange rate regimes—creates uncertainty for investors and undermines growth. Pakistan’s history of IMF entry, exit, and re-entry reflects a deeper governance issue: reforms rarely last beyond a single political cycle.

Economist Atif Mian notes: “PML-N masked imbalances, PTI exposed them abruptly, PDM delayed correction, caretakers enforced painful stabilizers, and the current government has yet to deliver structural reform.”

The UNESCAP Economic Outlook 2023 places Pakistan among the ten most policy-volatile economies globally, warning that unpredictability deters long-term investment.

The table shows Pakistan’s policy direction shifting drastically with every government. Investors cannot plan when rules change faster than business cycles.

“Confidence fuels investment; inconsistency extinguishes it.”

4. Industrial Weakness: A Fragile Productive Backbone

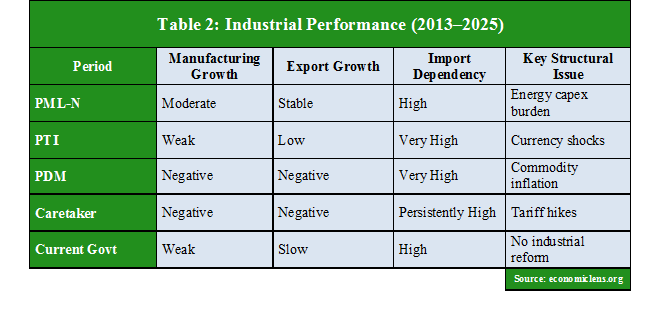

Pakistan’s narrow, low-value industrial base is unable to sustain growth, withstand global shocks, or generate diversified exports. Energy costs, input dependence, and technological stagnation hurt competitiveness. No government since 2013 has delivered meaningful industrial modernization.

Industrial economist Dr. Nadeem Haque states: “Pakistan has a consumption economy, not a production economy. No country prospers on imports and subsidies.”

The ADB Industrial Competitiveness Report 2024 ranks Pakistan lowest in South Asia for industrial productivity and export diversification.

The table exposes a stagnant industrial sector vulnerable to price shocks and policy uncertainty. No government implemented a long-term national industrial policy.

“Without industry, nations cannot grow; they can only endure.”

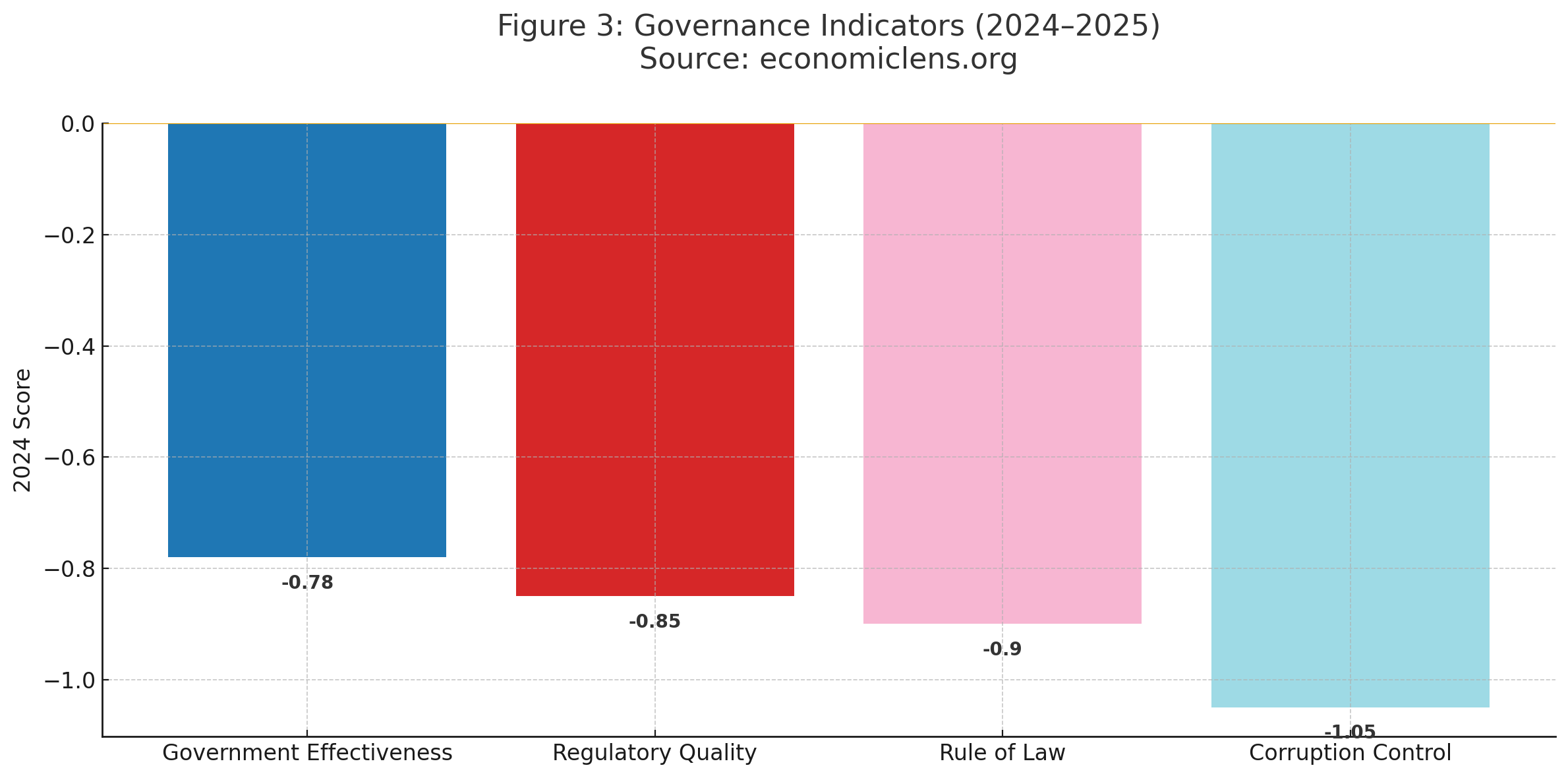

5. Governance Weaknesses: The Institutional Roots of Instability

Pakistan’s institutional weaknesses—regulatory uncertainty, bureaucratic inertia, corruption, and weak rule-of-law enforcement—undermine every aspect of economic performance. Governance failures make crises more frequent and recovery more difficult.

World Bank expert Daniel Kaufmann states: “When governance weakens, every economic shock becomes more damaging. Institutions—not politics—ultimately determine economic destiny.”

The World Bank Governance Indicators 2024 show Pakistan declining across all governance dimensions for the fifth consecutive year.

The scores reflect systemic dysfunction. Weak institutions raise business costs, deter investment, and reduce the effectiveness of reforms.

“Strong institutions build economies; weak ones break them.”

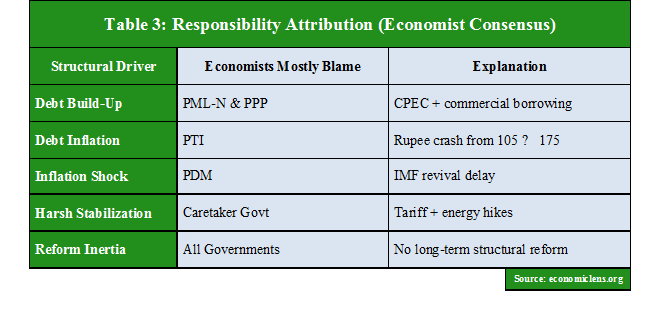

6. Interlocking Pressures & Expert Blame Attribution

Pakistan’s economic crisis is cumulative—built over decades, not years. Economists agree that each government contributed differently: PML-N created imbalances, PTI mismanaged corrections, PDM delayed stabilization, caretakers imposed painful measures, and the current government struggles to implement reforms.

LSE experts summarize: “No single government caused the crisis; each deepened structural vulnerabilities in different ways.”

PIDE’s Macro-Volatility Model 2024 concludes that political instability, policy inconsistency, and debt dynamics explain 72% of Pakistan’s economic volatility.

Responsibility is distributed, not concentrated. Pakistan’s crisis is structural, institutional, and cumulative—not personalized.

“Nations rise when they accept responsibility—and choose reform over repetition.”

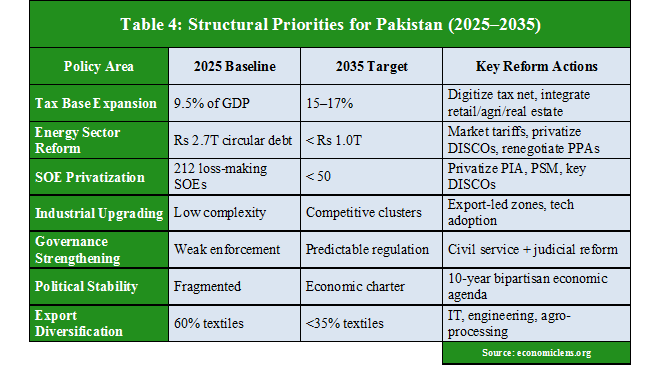

Policy Implications: Reforming the Foundations of Pakistan’s Economy

Pakistan’s economic instability will persist without structural transformation. Patchwork fixes, political quick-wins, and IMF firefighting cannot substitute for deep reform. Every major economic institution—taxation, energy, industry, and governance—requires redesign and modernization. Policy implications must be long-term, cross-party, and shielded from political cycles.

Harvard’s Graham Allison asserts: “Countries that outgrow economic fragility are those that build institutions strong enough to outlast politics.”

The OECD Reform Outlook 2025 shows that countries implementing ten-year structural reforms achieve significantly higher stability and investment.

The table reveals the scale of reform required to shift Pakistan from crisis management to sustainable growth. Strengthening the tax base, restructuring the energy sector, and reducing SOE losses are top priorities. Political consensus is the anchor without which no economic plan will survive.

“Reforms demand sacrifice—but without sacrifice, Pakistan cannot escape the gravitational pull of its past.”

Conclusion

Pakistan economic instability is rooted in deep structural weaknesses—debt overhang, political volatility, policy inconsistency, industrial stagnation, and weak governance. Each government from 2013 to 2025 contributed differently, but the crisis is structural, not personal. Only long-term, cross-party reforms can transform Pakistan’s economic destiny.

Call to Action

Pakistan must prioritize reform, stability, and institutional strength. Policymakers, economists, and citizens must demand a new economic architecture—one that replaces crisis cycles with sustainable growth.