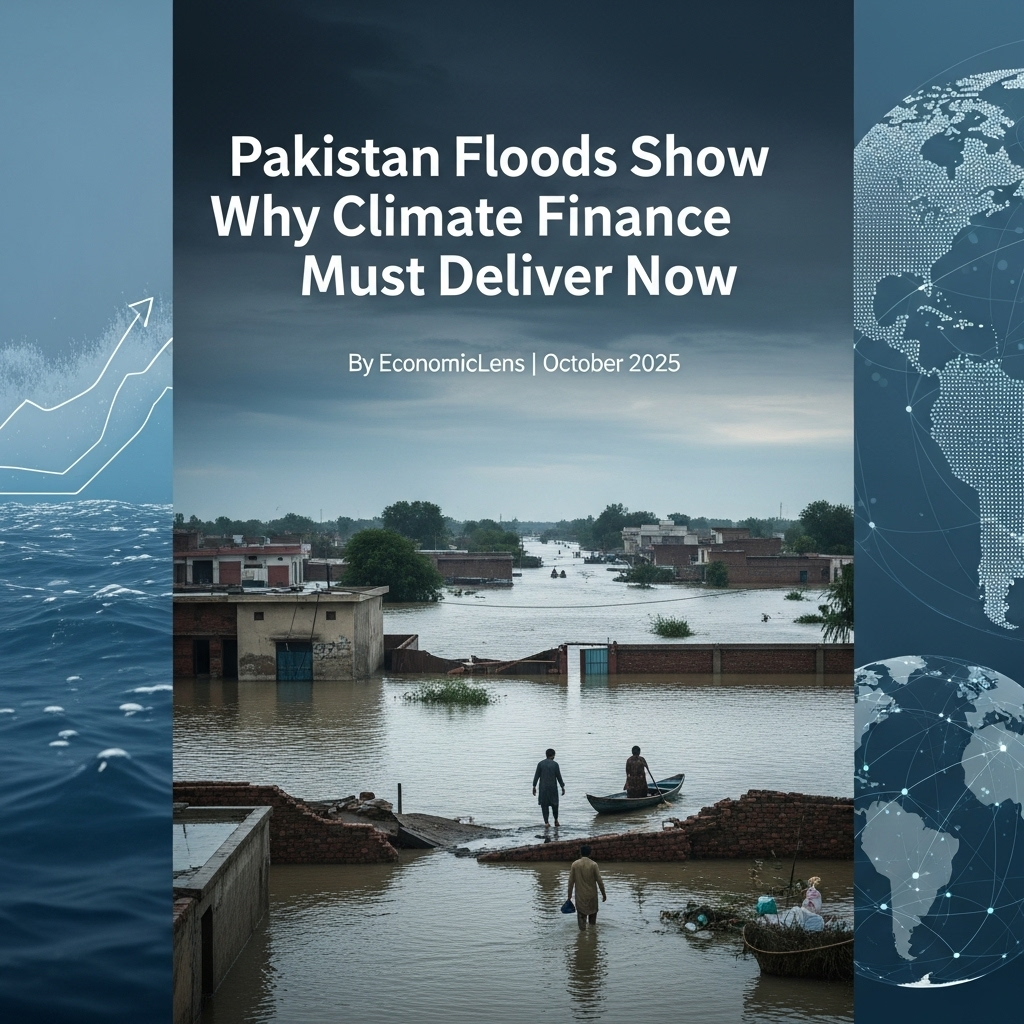

Exploring Pakistan’s relentless floods, this blog exposes the broken state of global climate finance—and calls for urgent, transparent reforms to turn empty pledges into real resilience and climate justice

A Crisis That Keeps Coming

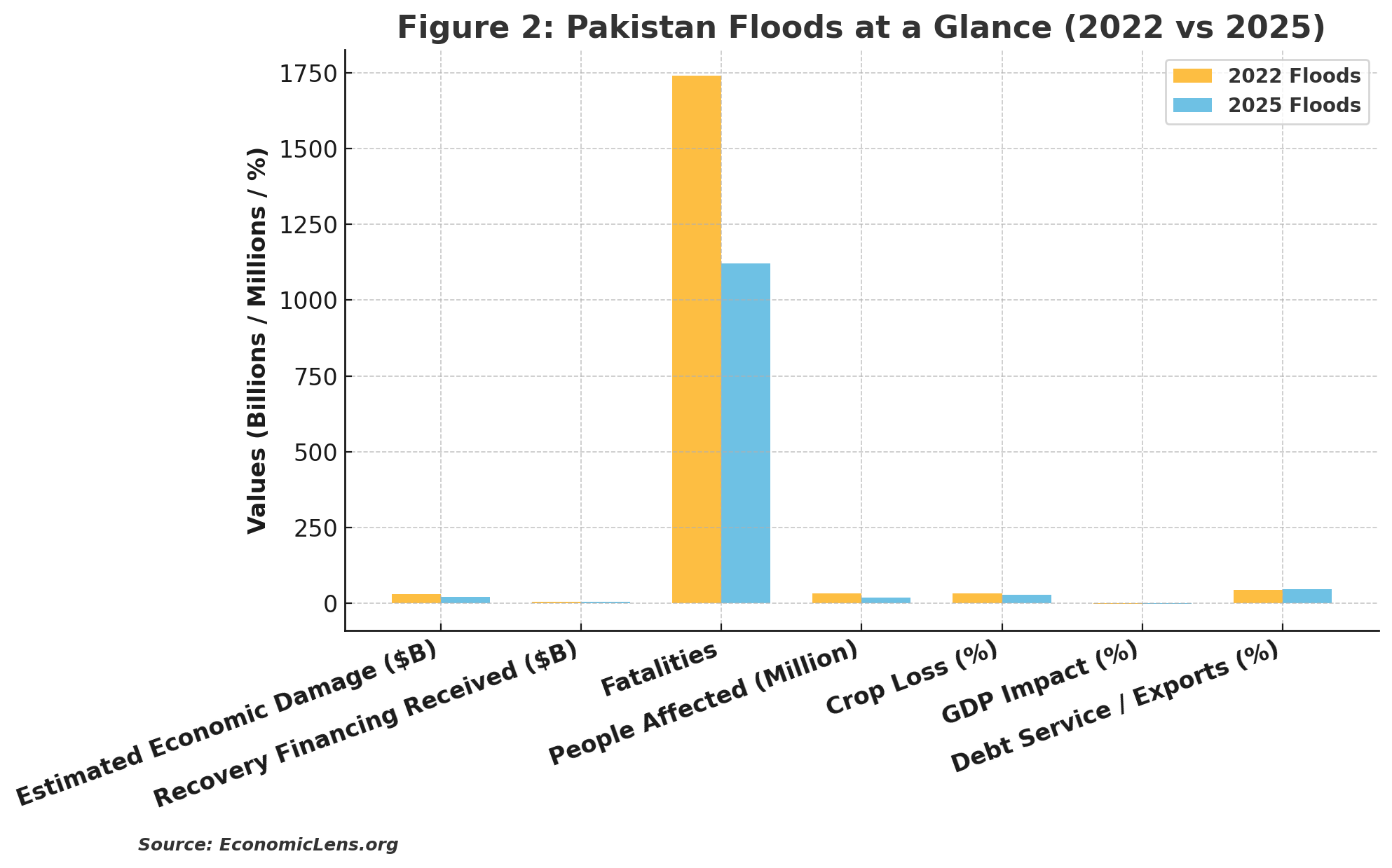

When Pakistan’s monsoon rains turned into walls of water again this summer, they didn’t just wash away homes—they exposed the world’s broken promises. Three years after the catastrophic 2022 floods that submerged one-third of the country and displaced over 30 million people (UN OCHA, 2022), the circumstances remain unaltered. What has changed is the urgency.

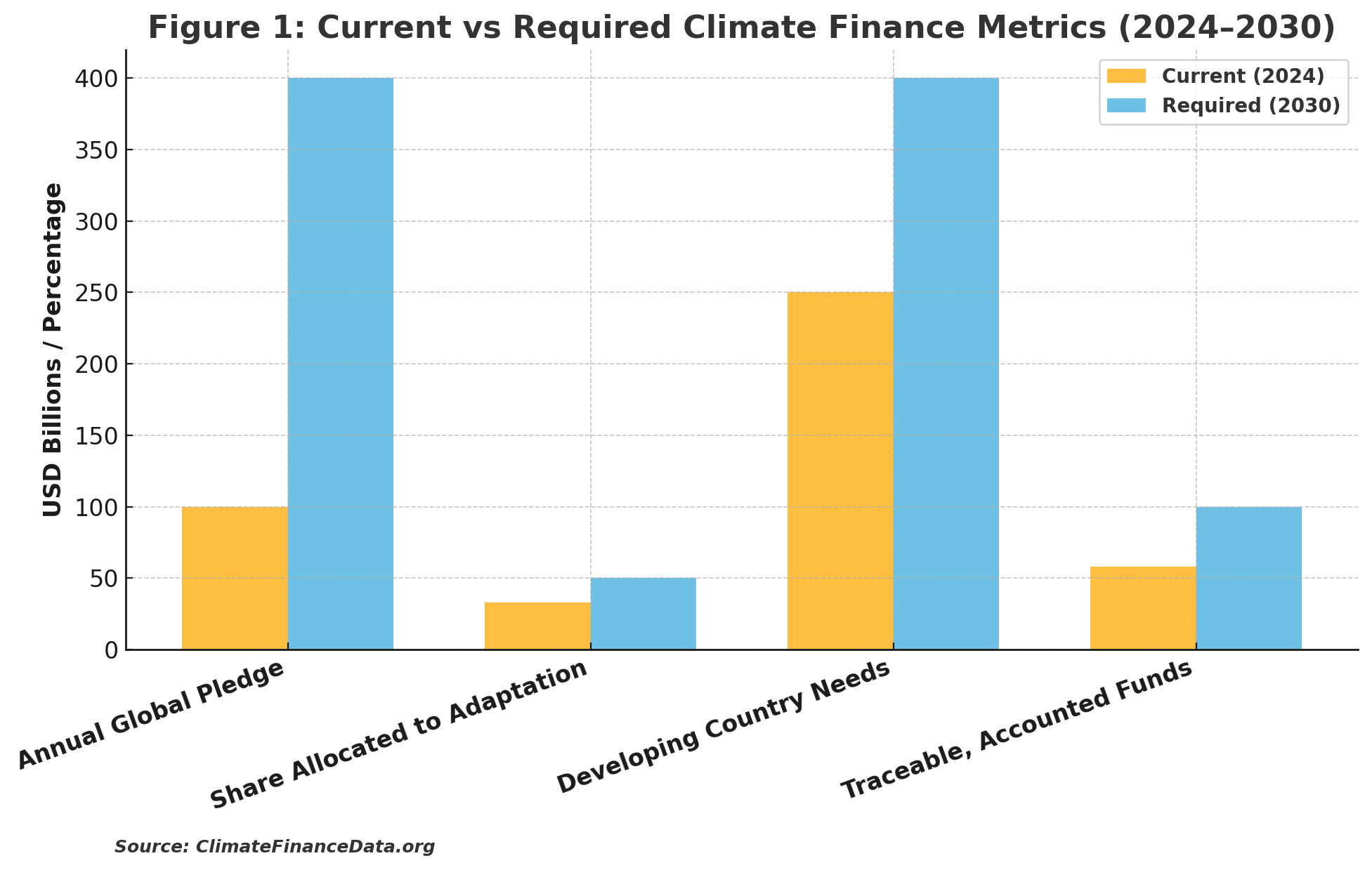

Despite several international commitments—especially the USD 100 billion annual climate-finance pledge set by the 2009 Copenhagen Accord (UNFCCC, 2009)—the resources allocated to support vulnerable nations in adapting to increasing climate problems remain mostly theoretical.

In 2025, Pakistan exemplifies the potential for the global climate-finance system to evolve from speeches to survival (UNEP, 2024).

The Unfinished Business of Climate Finance

The proposal to compensate developing nations for “loss and damage” originated at COP13 in Bali in 2007, grounded on the principle of climate justice (UNFCCC, 2007). It argued that those least responsible for global emissions should not bear the heaviest cost of their consequences.

Despite the establishment of the Loss and Damage Fund at COP28 in Dubai (UNFCCC, 2023), disbursements have been painfully slow. The UN Environment Programme (2024) estimates that developing countries would need over USD 400 billion annually by 2030 for adaptation, which is four times the pledged USD 100 billion

“the global financial response to climate change is insufficient, ambiguous, and inequitable”

Without the expansion of both financial resources and accountability, agreements will remain only symbolic as vulnerable nations drown in their own debt (OECD, 2024).

From Climate Justice to Debt Justice

Pakistan’s experience mirrors a larger crisis across the Global South: the climate–debt nexus. From Sri Lanka to Zambia, nations face the paradox of borrowing to rebuild from disasters caused by others’ emissions (IMF, 2025).

The Bridgetown Initiative 2.0 (Barbados, 2025) is pivotal to reform dialogues, advocating for debt alleviation, concessional funding, and the integration of “loss and damage” into sovereign finance (Mottley, 2025). The situation in Pakistan exemplifies this convergence, indicating that climate finance must also mean debt justice.

“When climate adaptation comes in the form of loans, it’s not resilience—it’s recursion”

Although damages have decreased, the recovery finance framework—primarily dependent on loans—continues to undermine fiscal sustainability. “Climate finance” often disguises itself as climate debt (Eckstein et al., 2024).

“Pakistan’s pilot “debt-for-climate swaps” aim to convert external repayments into domestic adaptation projects—a mechanism that could reshape global development finance (UNDP, 2024)”

The Human Geography of Climate Change

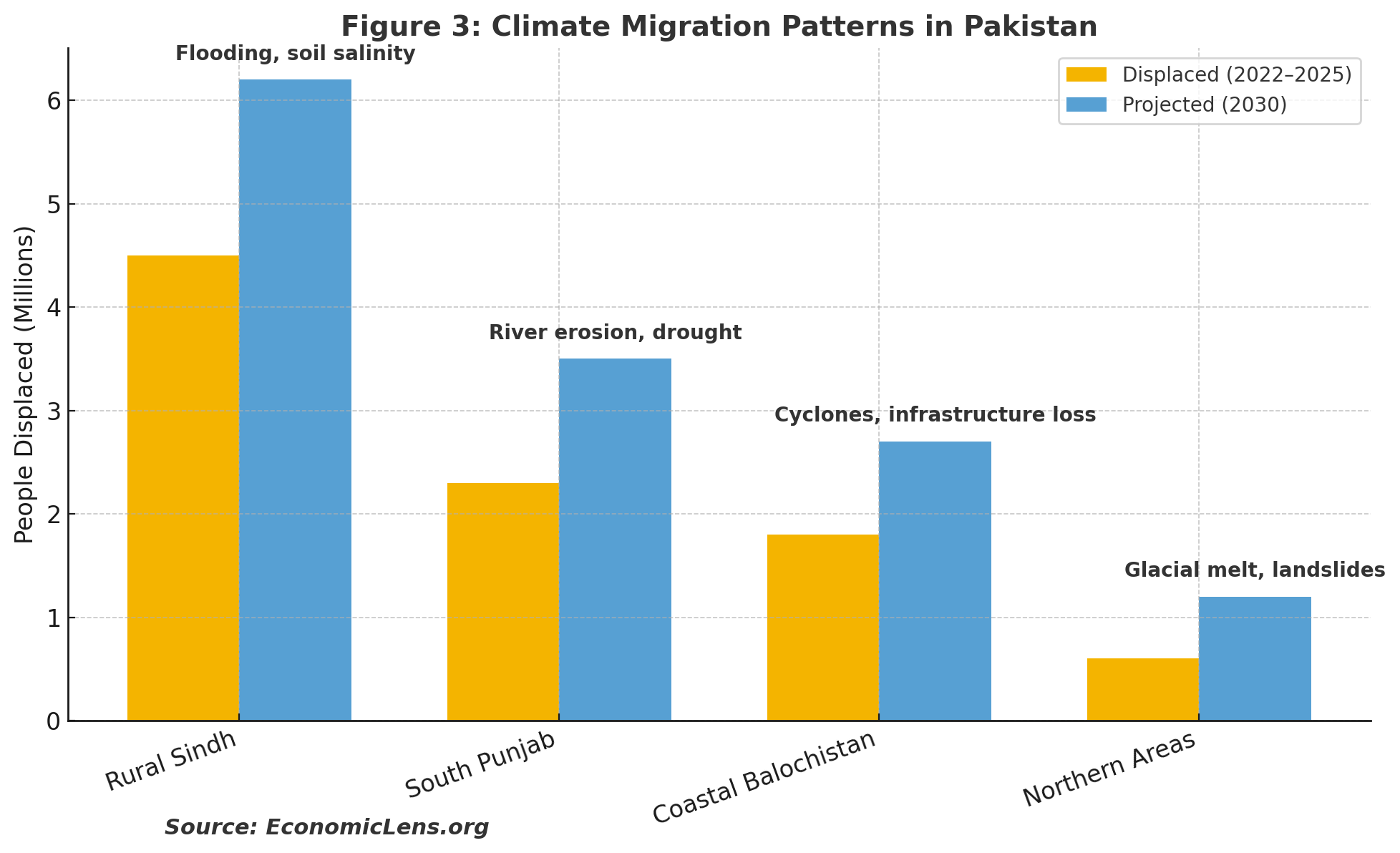

The floods are altering the demographic picture of Pakistan, in addition to economic consequences. Millions displaced from Sindh, southern Punjab, and Balochistan are migrating to major areas like as Karachi, Lahore, and Multan. These trends are transforming housing, labor markets, and social safety nets (IOM, 2025).

The International Organization for Migration predicts that Pakistan might face 10 million internal climate migrants by 2030 unless adaptation policies include livelihood restoration, women’s empowerment, and relocation support.

Data Sources: IOM (2025); NDMA (2024); PBS (2025)

These modifications underscore a fundamental truth: adaptation must prioritize people. Resilience finance must prioritize health, housing, and livelihoods, particularly for women farmers who have emerged as the principal agents of resilience (ADB, 2024).

“In Sindh’s resettlement camps, women farmers have become the first responder of resilience—rebuilding before institutions even arrive”

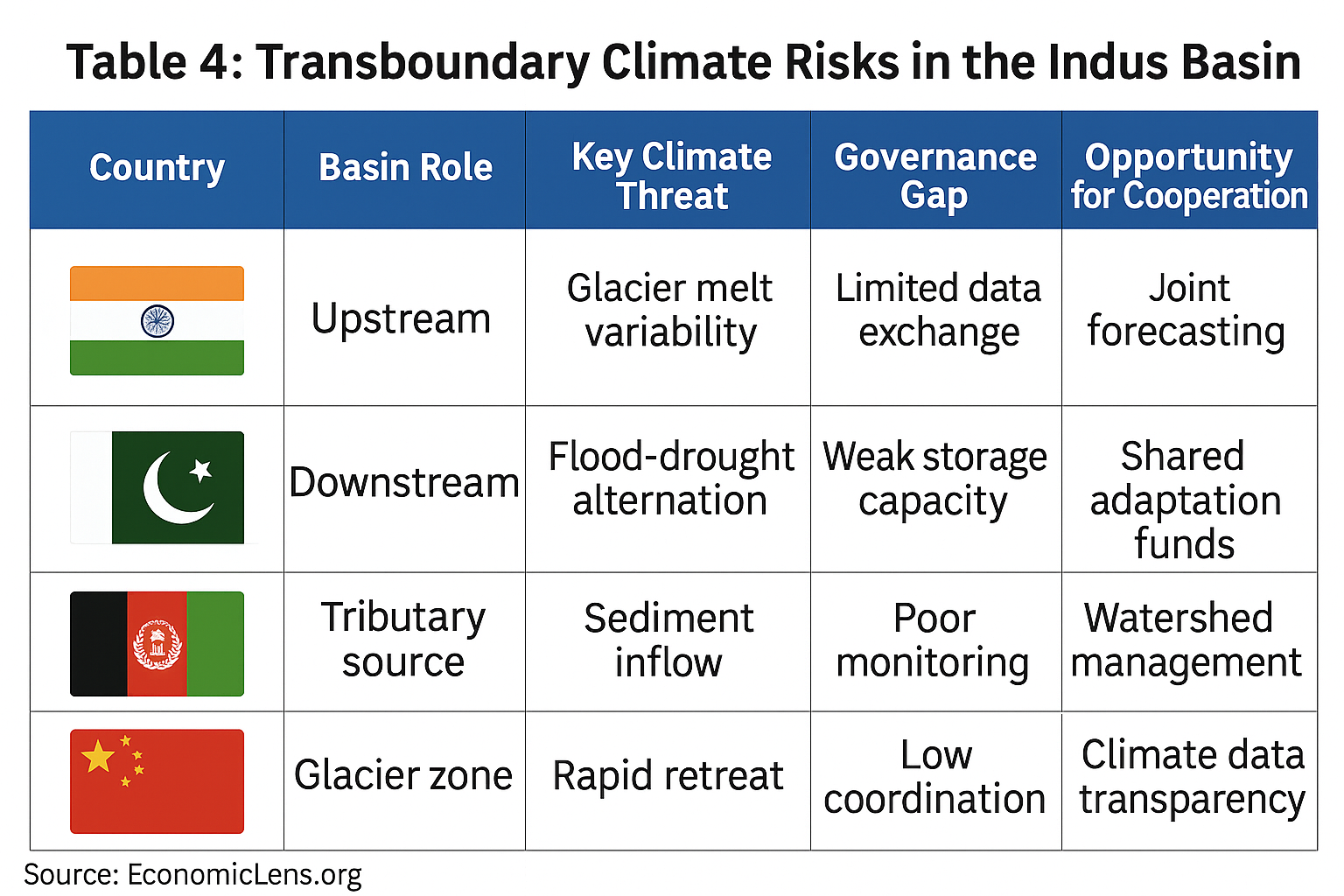

Regional Water Governance: Toward a South Asian Climate Compact

The Indus Basin, including Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, and China, is the ecological cornerstone of South Asia. Nonetheless, its governance, established by the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, is antiquated for a climate-volatile era (World Bank, 2025).

Glacial retreat and erratic monsoons need real-time forecasting, extensive data exchange across basins, and cooperative financial frameworks (ICIMOD, 2024). A South Asian Climate Compact might transform the Indus Basin into a cooperative resilience framework via collective insurance, adaptation bonds, and transboundary early warning systems (Qureshi et al., 2024).

Re-imagining Climate Finance: From Aid to Investment

Public pledges alone are inadequate to provide the necessary level of adaption. Pakistan’s USD 2 billion Climate Resilience Bond (2025) signifies a transition towards using private financing for measurable adaptation outcomes (Government of Pakistan, 2025).

Nevertheless, confidence is difficult to establish: just 58% of pledged climate funding can be traced from donor to project (OECD, 2024). Technology facilitates the attainment of transparency.

Tech for Trust: How AI Can Audit Climate Promises

AI dashboards, blockchain contracts, and satellite-based verification can precisely monitor every dollar allocated for climate initiatives (UNDP, 2024). Pilot projects in Sindh and Balochistan are now assessing blockchain-based financial oversight, providing real-time transparency to funders and the public (ADB, 2024).

“Transparency is not a luxury—it’s the foundation of climate credibility”

Policy Implications

Before the impending flood season, Pakistan’s experience offers insights not just for nations vulnerable to climate change but also for the global financial system at large. The gap between pledges and disbursements cannot be reconciled just via goodwill; it needs structural reform, enhanced efficiency, and enforced accountability.

To convert climate funding into a tool for resilience rather than indebtedness, five objectives arise:

- Automated Disbursement: Parametric insurance-style disbursements from the Loss and Damage Fund (UNEP, 2024).

- Integrate debt-for-climate swaps into the frameworks of the IMF and World Bank (IMF, 2025).

- Adaptation Financing Quota: Designate 50% of total global climate financing for adaptation (OECD, 2024).

- Regional Climate Governance: Establish a South Asian Climate Compact for basin-level cooperation (ICIMOD, 2024).

- Digital Accountability: Employ AI and blockchain supervision for every dollar allocated (UNDP, 2024).

If implemented, these solutions may transform global climate funding from a fragmented collection into a responsible and proactive protection for economies impacted by climate change.

“Policy reform, when driven by justice and transparency, turns crisis into credibility”

Research Insights

Understanding the economic ramifications of Pakistan’s floods requires an analysis that goes beyond simple rainfall and canals. It involves monitoring the movement of funds—or their lack—during flooding events.

The following conclusions emerge from current statistics and macroeconomic evaluations:

- Macroeconomic Linkage: Pakistan’s debt-service-to-export ratio (48%) exceeds pre-flood levels—resilience must be included into fiscal frameworks (World Bank, 2023).

- Equity in Adaptation: Seventy percent of displaced individuals migrate to informal settlements; hence, urban planning and land tenure reform are necessary (IOM, 2025).

- Financial Efficiency: Only 58 cents of each pledged dollar are designated toward verified projects (OECD, 2024).

- Regional Opportunity: Joint management of the Indus Basin might provide annual savings of USD 3–5 billion (ICIMOD, 2024).

- The Climate Resilience Bond illustrates investor interest in securities connected to adaptation (Government of Pakistan, 2025).

These findings emphasise a crucial principle: resilience is an economic investment rather than a humanitarian expense.

The Road to COP29: From Rhetoric to Resilience

As COP29 approaches in Baku, the international community faces a pivotal question: will the Loss and Damage Fund evolve beyond symbolic significance? Pakistan’s circumstances need more than just sympathy; they demand a thorough reform.

- Automated disbursements for verified losses

- Debt relief across all climatic systems

- Allocation of 50% for adaptation funds

- Regional governance for cooperative ecosystems

- Clear, digital fund supervision

These modifications might transform climate funding from a reactive instrument into a fundamental element of global economic stability (UNEP, 2024).

What Pakistan Teaches the World

The persistent floods in Pakistan are not singular disasters; they reflect the fragility of international obligations. Climate funding has evolved from an act of goodwill to an issue of justice, credibility, and existence.

If the world can sustain trillion-dollar carbon markets and defense budgets, it can surely fund resilience.

“Pakistan is not asking for charity—it is asking for the world to honor its contracts with the future. Climate finance must deliver—not tomorrow, not at the next COP—but now”