The Reko Diq copper-gold project marks Pakistan’s largest mineral revival, unlocking vast resources, attracting global investment and strengthening export potential. This blog explains how Pakistan can convert mineral wealth into development, improve governance, avoid the resource-curse trap and reduce reliance on IMF financing.

Introduction: Reko Diq Copper-Gold Project

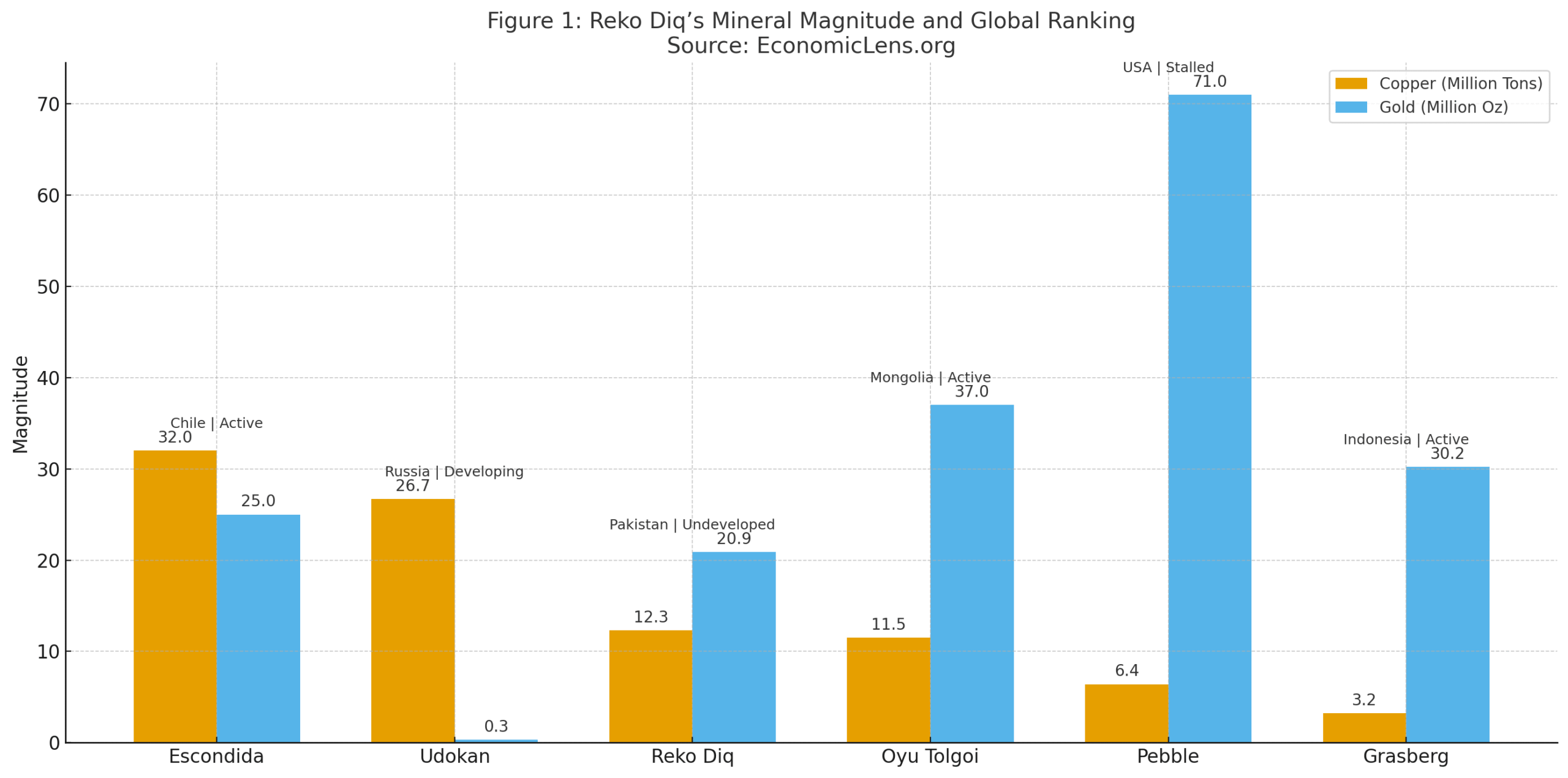

The Reko Diq copper and gold project exposes Pakistan’s deepest economic contradiction. The country owns one of the richest untapped mineral deposits on the planet, yet remains trapped in debt cycles, IMF programs and chronic structural poverty. With 12.3 million tons of copper and 20.9 million ounces of gold, Reko Diq holds the potential to reshape Pakistan’s long-term economic trajectory. This is the type of deposit that builds sovereign wealth funds, industrial clusters and national prosperity.

Yet for decades, political interference, cancelled agreements, institutional fragility and costly arbitration disputes turned this world-class asset into a symbol of economic mismanagement. Countries with smaller deposits built export pipelines, downstream industries and fiscal buffers. Pakistan produced delays, instability and penalties.

Reko Diq is not just a mining project. It is a case study in how governance failure destroys national opportunities. This blog evaluates how Pakistan wasted a generational economic transformation, why global peers succeeded with less, and what urgent reforms are needed to prevent another lost decade.

1. Geological Significance of the Reko Diq Copper-Gold Project

Reko Diq lies within the Tethyan Metallogenic Belt, one of the world’s richest mineral corridors. With 12.3 million tons of copper and 20.9 million ounces of gold, its scale places Pakistan alongside major mineral economies. Yet weak governance, fragmented regulation and decades of political instability prevented Pakistan from converting this geological advantage into national wealth. The gap between what Pakistan owns and what Pakistan delivers defines its resource paradox.

Reko Diq is large enough to reposition Pakistan in the global copper market. Yet countries with similar or even smaller deposits, such as Chile, Mongolia and Indonesia, built mining-led industrial bases, export pipelines and sovereign wealth buffers. Pakistan produced delays, disputes and penalties.

Global datasets, including the United States Geological Survey

(https://www.usgs.gov/), show that countries with transparent institutions convert mineral endowments into long-term prosperity. Pakistan’s system failed around the resource.

1.1 Why Reko Diq’s Copper-Gold Reserves Matter Globally

Countries with functioning institutions transform minerals into exports, jobs and fiscal strength. Pakistan transforms minerals into court cases and IMF repayment cycles.

A parallel analysis from our 27th Constitutional Amendment blog shows how weak institutional checks undermine long-term planning. The same governance fragilities now constrain the Reko Diq project.

https://economiclens.org/pakistans-27th-constitutional-amendment-power-centralization-judicial-overhaul-the-new-civil-military-order/

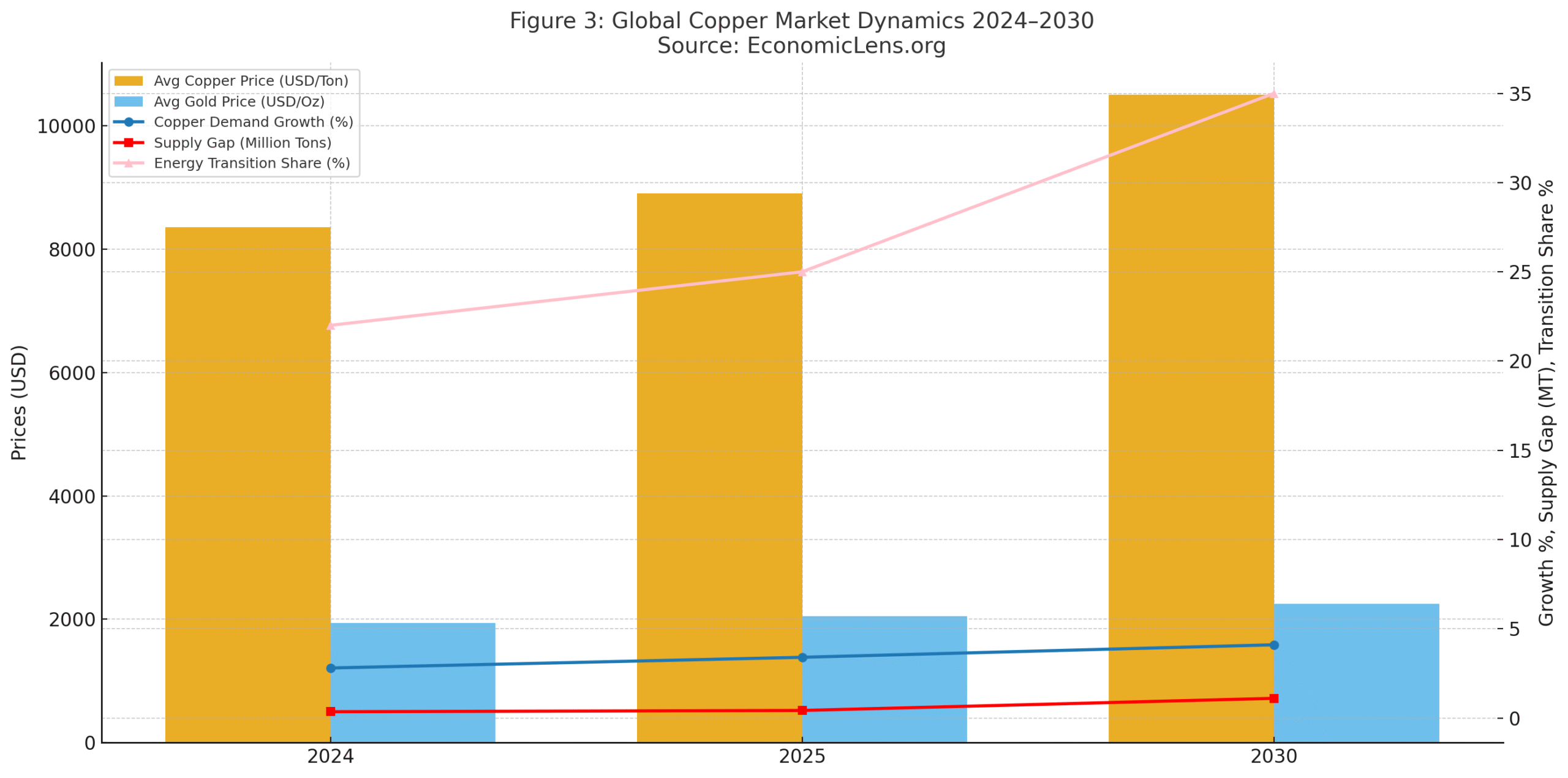

Global Copper Market Dynamics (2024–2030)Pakistan remained idle during a decade when copper prices surged, supply gaps widened and global demand intensified. Countries with efficient mining systems captured the boom. Pakistan observed it from the sidelines.

1.2 Copper’s Geopolitical Importance and Why the Reko Diq Mine Pakistan Matters

Copper today is a strategic mineral that powers electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, energy storage, data centers and global digital infrastructure. China, the United States and the European Union classify copper as critical for their energy transitions and technological security.

The European Commission’s Critical Raw Materials Assessment (https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/) reinforces this strategic priority.

This means the Reko Diq copper and gold project is not only an economic asset. It is a geopolitical instrument. Global powers compete for copper. Pakistan holds a top tier deposit but has not leveraged it strategically.

1.3 Global Copper Boom: Pakistan Missed the Moment

During the last global copper shortage, producers enjoyed windfalls as companies scrambled for supply. Nations with active mining sectors saw exports rise and fiscal buffers strengthen.

Pakistan contributed nothing because Reko Diq remained inactive.

“Resource wealth creates potential. Governance converts it into prosperity”

2. Economic Impact, Jobs, Exports & Fiscal Stability

The Reko Diq copper and gold project could have transformed Pakistan’s foreign exchange position. Instead, repeated delays forced the country into deeper debt, higher borrowing costs and greater IMF dependence. While Pakistan struggled to stabilize reserves, a multi billion dollar export engine remained untouched.

2.1 Economic Impact of the Reko Diq Copper-Gold Project on Exports and Fiscal Strength

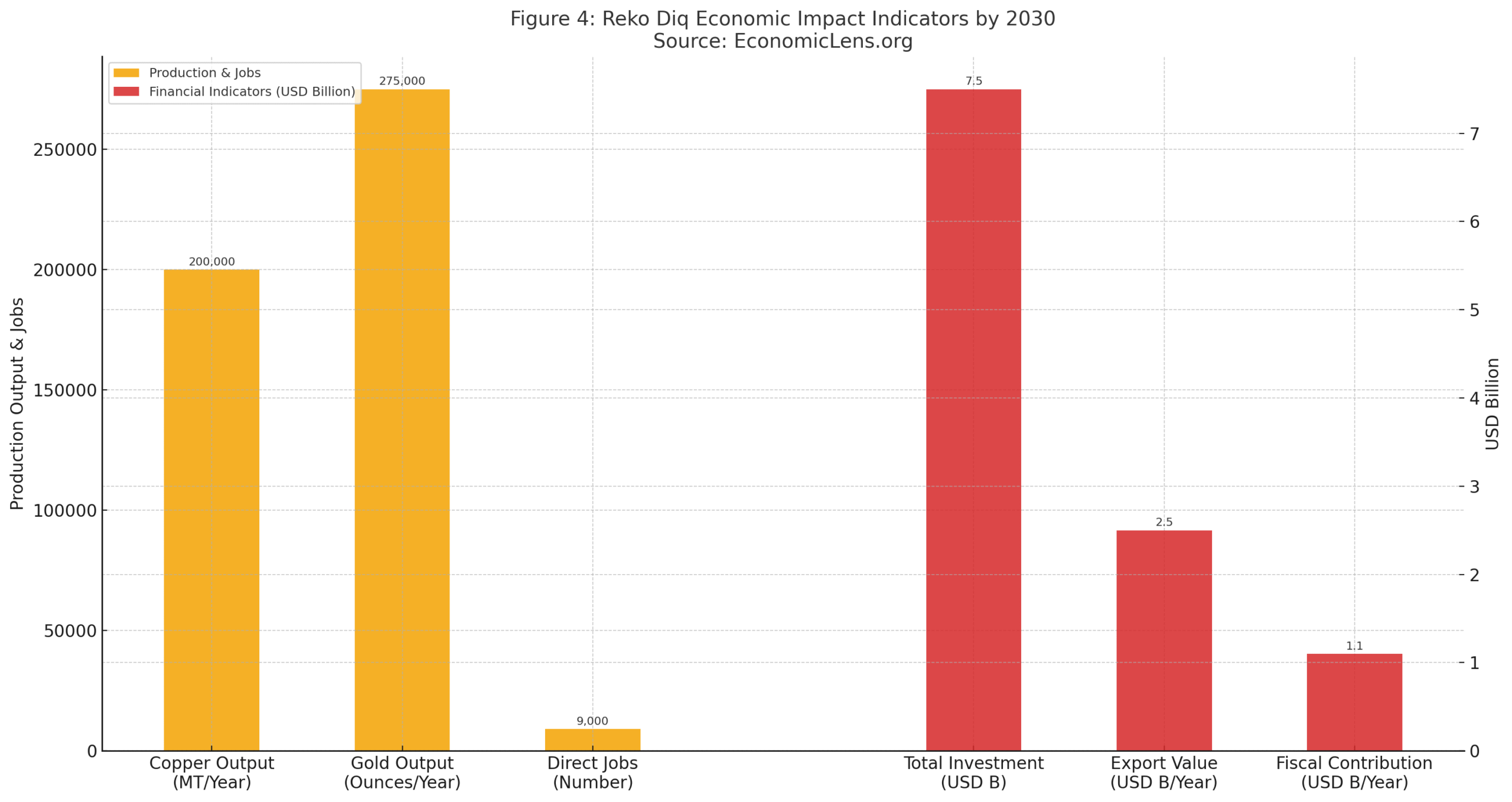

The Reko Diq copper and gold project had the capacity to generate several billion dollars each year. Instead of building a mineral driven export engine, Pakistan borrowed externally and slipped deeper into fiscal stress. The economic loss from delays already exceeds the revenue the mine will produce in its first decade. The World Bank’s Pakistan Development Update warns that delays in mineral development significantly weaken fiscal stability.

(https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/pakistan/publication).

2.2 Long-Term Revenue Potential from the Reko Diq Copper-Gold Project

Copper prices move in sharp global cycles. Countries that benefit from mining adopt hedging tools, stabilization funds and sovereign wealth buffers to smooth volatility. Pakistan has none of these mechanisms. Without proper risk management, revenue from the Reko Diq copper and gold project will rise and fall with global price swings, creating instability in the budget. Unless Pakistan builds buffers, it will face the same boom and bust cycles that damage resource dependent economies.

2.3 Employment, Skills Gaps & Local Labor Needs for the Reko Diq Mine Pakistan

Reko Diq can generate thousands of jobs, but Pakistan does not have enough skilled mining labor. Without targeted training and technical programs, foreign workers will capture high value positions while locals remain confined to low skill roles. This will create resentment, weaken community support and reduce the domestic economic multiplier.

2.4 How Pakistan’s Copper-Gold Reserves Can Outperform Entire Export Sectors

Pakistan’s textile sector struggles to increase exports by even 1 billion USD in a year. The Reko Diq copper and gold project on its own can produce 3 to 4 billion USD annually. Pakistan’s dependence on low value exports rather than high value minerals resulted in decades of missed growth. Global trade data from UNCTAD shows that countries dependent on low value exports experience chronic balance of payments pressure and slow structural transformation (https://unctad.org/statistics).

“High value minerals can deliver what low value exports never could. They offer stability, diversification and sustainable foreign exchange.”

3. Governance Fragility Undermining the Reko Diq Copper-Gold Project

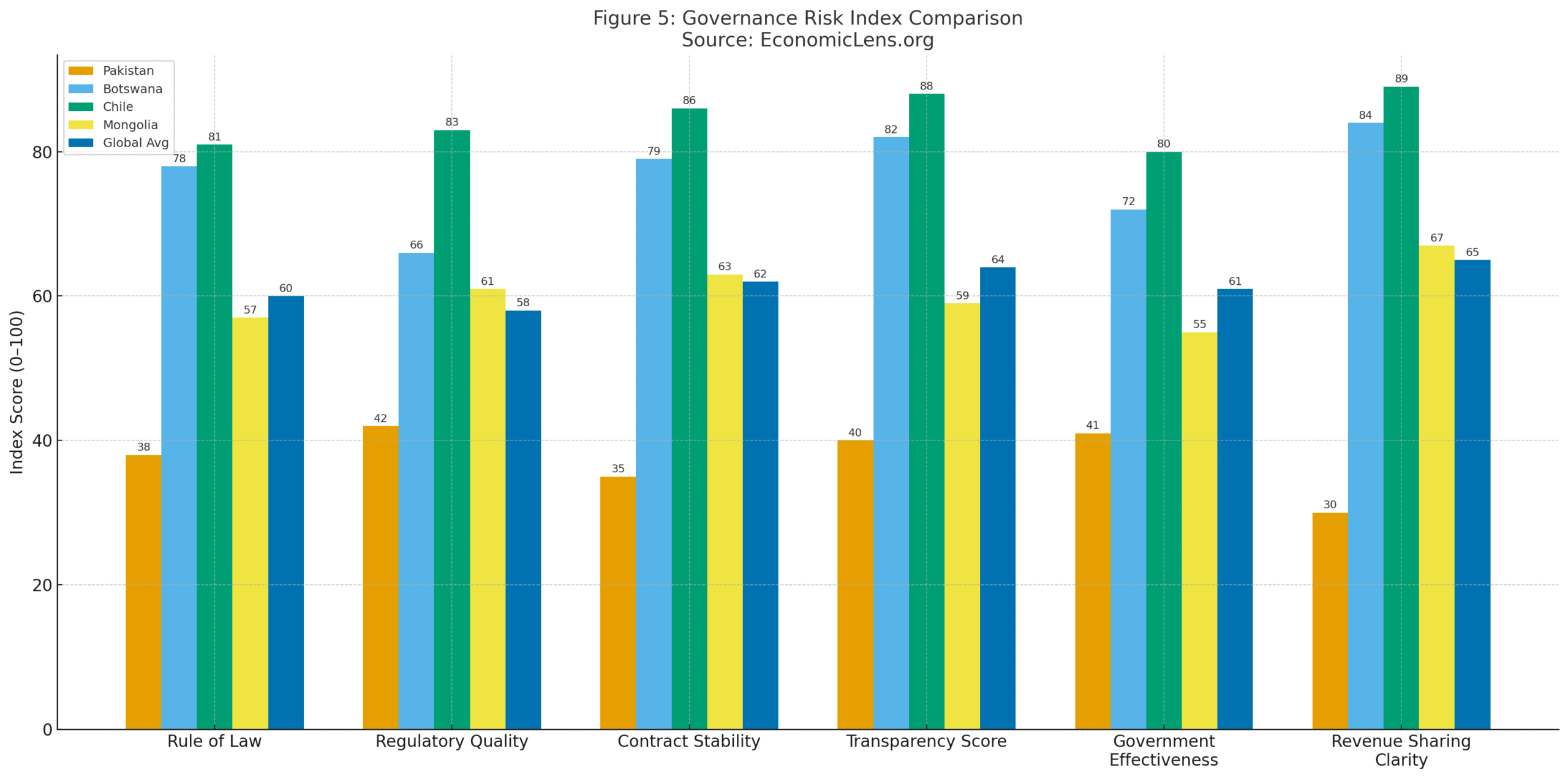

The Reko Diq copper and gold project is a clear example of how weak governance can block even the most promising economic opportunities. Large scale mining requires stable laws, predictable regulations and long-term planning. Yet Pakistan’s institutions repeatedly failed to provide the confidence needed for a project of this size. Instead of building a mining economy around a world-class deposit, Pakistan became a cautionary lesson in global investment circles.

3.1 Governance Quality vs Global Mining Leaders: Lessons for the Reko Diq Mine Pakistan

Countries that convert mineral deposits into long-term prosperity are those with predictable laws, transparent institutions and stable contracts. Comparative evidence from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators shows that strong institutional quality is the single most important factor driving long-run success in natural resource development (https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/). Pakistan does not struggle because it lacks resources. It struggles because its institutions block the conversion of those resources into national development.

3.2 Regulatory Gaps Hindering the Reko Diq Copper-Gold Project

Pakistan still operates without a modern mining code. Licensing procedures are outdated, overlapping federal and provincial jurisdictions create confusion and environmental oversight remains fragmented. There is no unified digital cadaster, no geological mapping aligned with international benchmarks and no central authority capable of coordinating water, infrastructure and environmental planning for mining regions.

These structural gaps create delays, raise uncertainty and weaken investor trust. The Reko Diq copper and gold project suffered because the regulatory system was never designed to support long-term, high-value mineral development.

Pakistan’s most damaging weakness is policy inconsistency. Political changes repeatedly overturned agreements, shifted priorities and introduced uncertainty that forced investors to pause or reconsider commitments. When institutions are unpredictable, long-term projects lose momentum. Pakistan spent more time renegotiating, disputing and reversing decisions than developing the mine, and the opportunity cost was immense.

3.3 Investor Confidence, Arbitration & Sovereign Risk Linked to the Reko Diq Mine Pakistan

Mining companies assess sovereign risk with great caution. Pakistan is viewed as a high-risk jurisdiction because agreements have collapsed in the past and because courts, ministries and provinces often work without coordination. The 5.8 billion dollar arbitration penalty became global news and reinforced Pakistan’s image as a country where contracts carry high uncertainty and high exit costs.

Global reporting, including Reuters coverage of the Reko Diq arbitration dispute, highlighted Pakistan’s contract instability and sovereign risk concerns (https://www.reuters.com/world/). As a result, investors demand higher returns, stricter protections and slower rollout timelines. This sovereign risk premium is one of the largest hidden costs Pakistan pays for weak governance.

The arbitration dispute over the Reko Diq copper and gold project became a turning point. Investors observed how Pakistan engaged in a long legal confrontation that ended in massive penalties. Although the eventual settlement revived the project, the reputational damage had already spread. Countries with predictable legal systems attract investment. Countries with unpredictable systems attract hesitation and caution.

“A nation rich in minerals cannot prosper when its institutions restrict progress instead of enabling it.”

4. Provincial Impact, Environment & Social Risk: Reko Diq Mine Paksitan

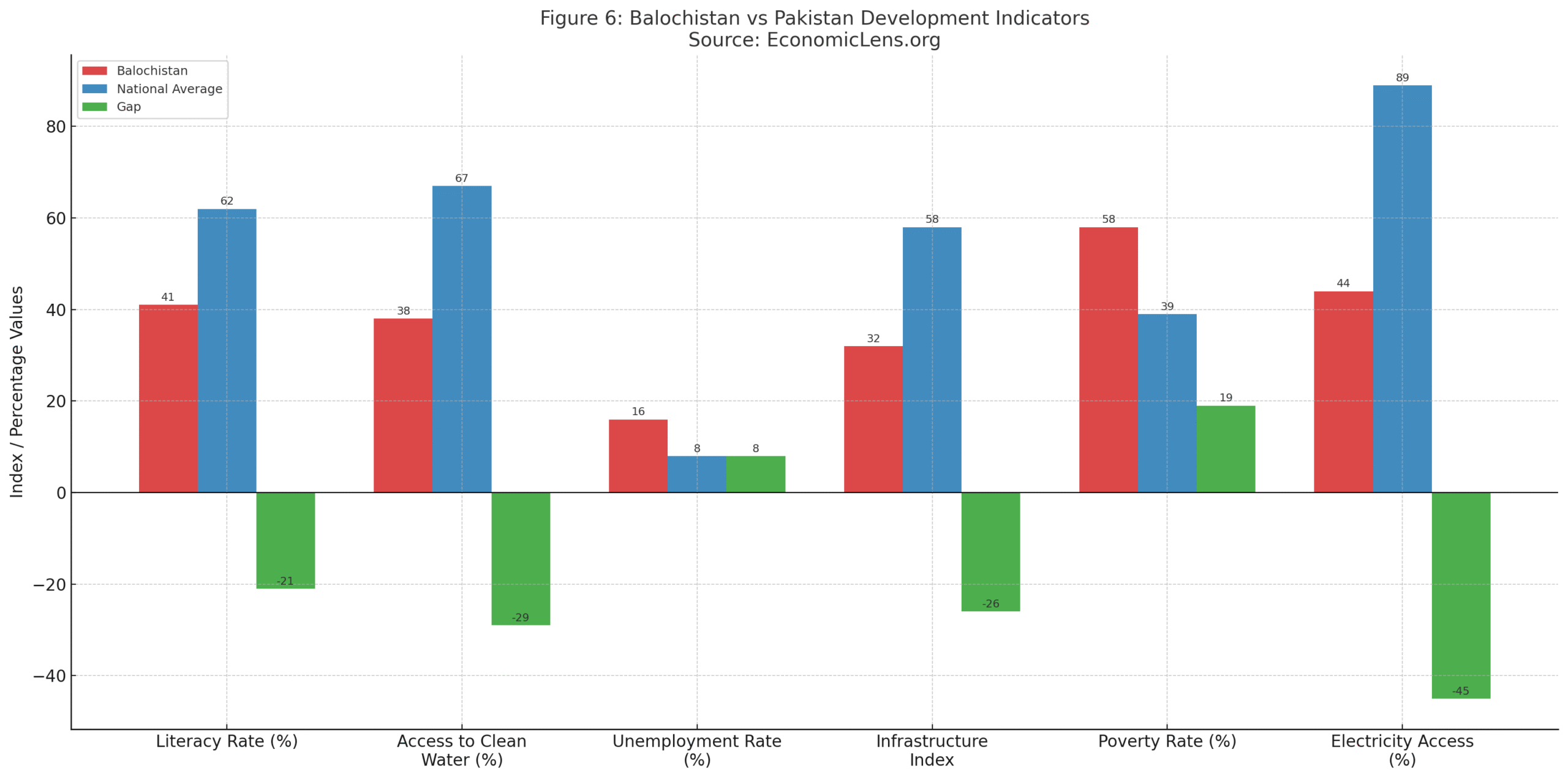

The Reko Diq copper and gold project lies in Balochistan, a province that has experienced decades of underdevelopment despite its mineral wealth. Local communities often associate extraction with exploitation rather than opportunity. Severe deprivation, environmental pressures and security concerns make social acceptance a decisive factor in the long-term viability of the project. Without inclusive development, no mining venture can operate sustainably in Balochistan.

4.1 Balochistan’s Development Gap and Expectations from the Reko Diq Mine Pakistan

The social contract in Balochistan remains fractured. Without visible improvements in services, employment and household incomes, communities will continue to view large-scale extraction as another chapter in a long history of wealth leaving the province while poverty remains entrenched.

The Reko Diq copper and gold project sits in a politically sensitive province that has long demanded greater authority over its natural resources. After the 18th Amendment, disputes over ownership, royalties and fiscal control became more pronounced. These disagreements repeatedly slowed progress and deepened mistrust.

As our analysis on Higher for Longer Interest Rates explains, Pakistan’s debt pressure and fiscal stress often intensify centre and province conflicts over resource revenue allocation.

(https://economiclens.org/higher-for-longer-interest-rates-sovereign-debt-stress-fiscal-fragility/)

Without a stable and transparent revenue sharing framework between Islamabad and Quetta, Reko Diq will remain exposed to political frictions.

4.2 Water Scarcity & Environmental Risks Affecting Pakistan’s Copper-Gold Reserves

Chagai is one of the driest districts in Pakistan. Mining requires significant water, and local communities fear that extraction will reduce their already limited supply. Water scarcity is only one dimension of the challenge. International guidelines such as the UNEP Mining Environmental Framework outline how water stressed regions should regulate mining and environmental risk (https://www.unep.org/resources). Large mines generate tailings, dust emissions and heavy waste, which require strong safeguards and strict monitoring. Pakistan currently lacks robust environmental oversight in mining districts. If these risks are not managed effectively, they can trigger community resistance, legal disputes and costly delays.

4.3 Deficits & Security Challenges Near the Reko Diq Copper-Gold Project

Large copper mines depend on reliable infrastructure. Reko Diq is located in a region with limited roads, weak electricity supply, no industrial water systems, insufficient telecommunications and inadequate logistics. Barrick Gold will be forced to invest heavily in basic operational infrastructure. The absence of state-led development in this area reflects deeper governance neglect and significantly raises operational costs.

The region has a long history of conflict, economic deprivation and political grievances. This environment increases operational risk. High poverty and limited state services make communities suspicious of external actors. Without inclusive development, transparent communication and sustained engagement, mining operations may encounter resistance.

For decades, small-scale mining in Balochistan extracted minerals while communities saw almost no improvement in their living conditions. This legacy shapes today’s skepticism toward Reko Diq. Locals have witnessed minerals being transported out of the province while schools, clinics, roads and water systems remained neglected. Trust will not be restored with promises. It will be restored with visible and measurable change.

Similarly, across Latin America, several copper and lithium mines were forced to shut down because promised development never reached local communities. These shutdowns cost governments and companies billions. Pakistan must avoid similar outcomes by delivering clear and tangible development benefits in Chagai.

“A mining project cannot succeed when the host community remains poor, water stressed and unheard.”

5. Value-Addition & Downstream Strategy: Unlocking Full Value from the Reko Diq Copper-Gold Project

The true economic strength of the Reko Diq copper and gold project will not come from exporting raw ore. It will come from processing that ore into refined copper, rods, wire and eventually advanced components used in electronics, renewable energy systems and industrial machinery. Countries that mastered this shift moved from resource dependence to industrial leadership. Pakistan, however, has historically exported low-value material and imported high-value goods, locking itself into a permanent structural imbalance.

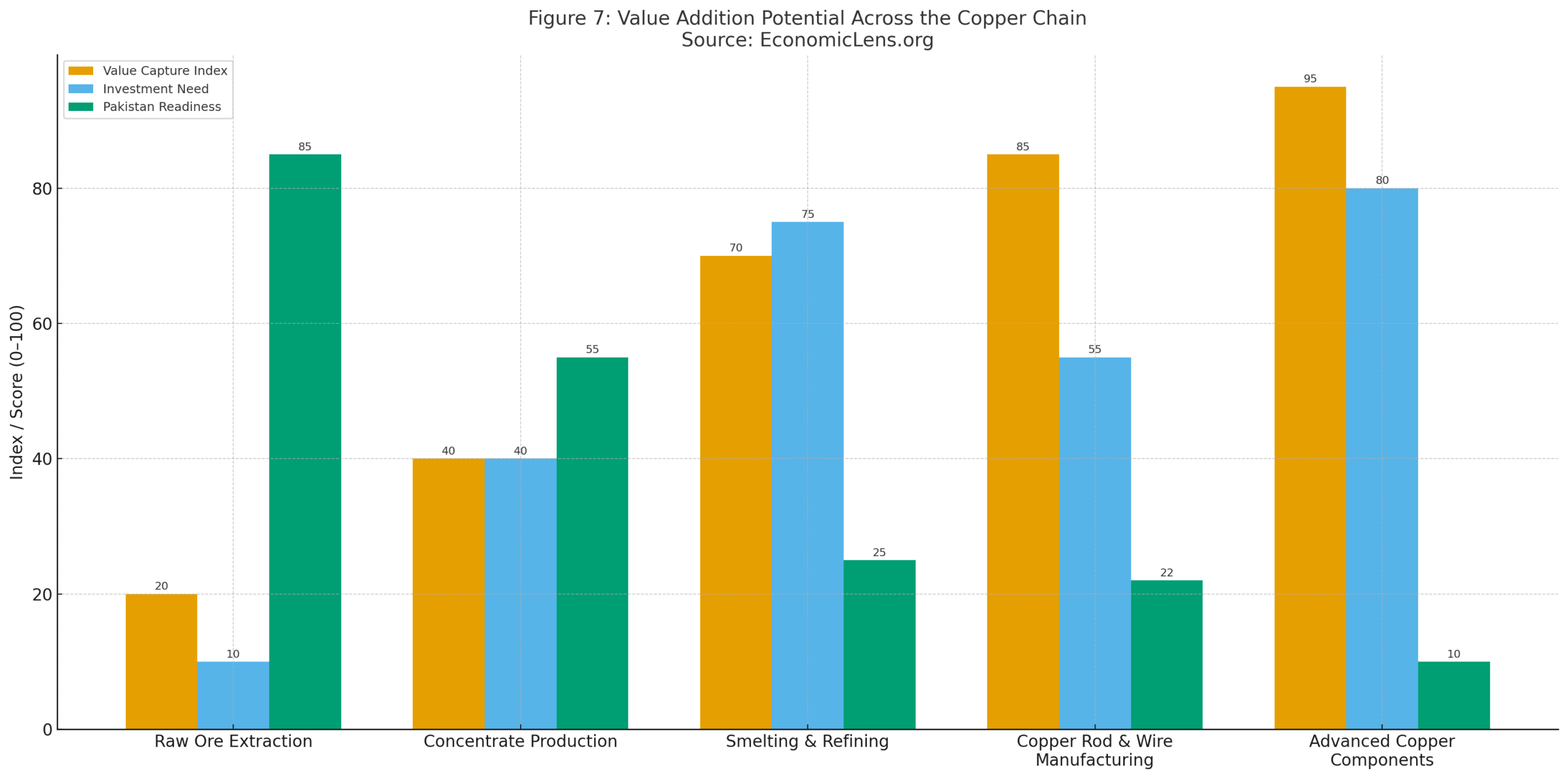

5.1 Value Capture Potential Across the Reko Diq Copper Supply Chain

Without smelting and refining capacity, Pakistan captures only about twenty percent of the copper value chain. Countries that invest in downstream processing capture up to ninety five percent. If Pakistan ignores the industrial components of the copper sector, the Reko Diq copper and gold project will benefit foreign manufacturers far more than the domestic economy.

5.2 Global Benchmarks for Developing Copper-Gold Reserves: What Pakistan Must Learn

Chile did not become the world’s largest copper exporter by relying on ore extraction. It built smelters, refineries, research centres and manufacturing clusters. China created one of the world’s largest refining capacities by supporting energy infrastructure, industrial zones and logistics networks. Kazakhstan linked its mines with smelting plants and copper wire factories, creating a complete industrial ecosystem.

International datasets from the International Copper Study Group show that countries dominating copper markets rely on strong downstream capacity rather than raw extraction alone. (https://www.icsg.org/)

These pathways make one fact clear. Downstream capacity does not emerge naturally. It must be created through long-term strategy, targeted incentives and coordinated public and private investment.

A downstream copper industry can improve Pakistan’s external account, generate high-quality employment and diversify the export basket. It can also anchor new manufacturing sectors such as motors, cables, transformers, turbines and renewable technology components. Without downstream development, Pakistan will export its opportunity and import its future.

This pattern mirrors the weakness highlighted in our Global Migration Economics 2025 analysis, where the absence of high-value industry keeps Pakistan dependent on external financial inflows.

https://economiclens.org/global-migration-economics-2025-demographic-imbalance-remittance-dependence/

5.3 Avoiding the Saindak Outcome: Strategic Lessons for the Reko Diq Mine Pakistan

The Saindak copper project should have served as a foundation for industrial learning. Instead, Pakistan repeated the old pattern. Ore was extracted, sold cheaply and processed abroad. Local development remained limited, infrastructure stayed weak and the province gained little beyond modest royalties and temporary jobs. Reko Diq must not follow the same trajectory. The difference between failure and transformation will depend on whether Pakistan commits to developing downstream industries.

“Extraction creates revenue. Processing creates power. For long-term economic strength, Pakistan must move from exporting raw ore to exporting finished value.”

6. Policy Pathway: Turning Reko Diq Mine Pakistan into Real Economic Transformation

Reko Diq exposes deep gaps in Pakistan’s governance, planning and development systems. Yet it also offers a rare opportunity to redesign the national mineral policy in a way that supports long-term growth. If managed well, this project can strengthen institutions, empower provinces and modernize industry in ways Pakistan has never achieved before.

6.1 Contract Stability and Legal Predictability

Long-term investment requires consistency. Pakistan must provide agreements that endure beyond political cycles, clear dispute resolution pathways and a judiciary that supports continuity instead of uncertainty. Investors must trust that rules will not shift without reason.

6.2 Transparent Mineral Revenue Framework

Pakistan needs a revenue-sharing model that is simple, transparent and fair. Balochistan must receive visible and guaranteed shares of project income so that communities experience improvements in services, infrastructure and employment.

6.3 Local Development and Skills Investment

Mining regions must benefit directly. This includes technical training centres, local hiring programmes, new infrastructure and steady improvements in water, power and connectivity. Visible development builds trust, and trust strengthens long-term stability.

6.4 Downstream Copper Industries

Pakistan must commit to processing copper rather than exporting raw ore. The country cannot afford to repeat the Saindak outcome. A national copper strategy should link mining operations with smelting, refining, rod production and manufacturing clusters.

6.5 National Mineral Authority

Mining governance must be unified. A national mineral authority can streamline approvals, coordinate with provinces, maintain geological data and ensure professional oversight for all major mineral projects.

6.6 Sovereign Mineral Wealth Fund

Revenue from Reko Diq should support long-term development rather than short-term political spending. A sovereign fund can stabilize income, finance education and infrastructure and provide a buffer during global price downturns.

“Minerals alone cannot transform a country. Strong institutions, long-term planning and fairness can.”

7. Future Scenarios: Pakistan With and Without Reko Diq Mine Project

The next two decades will determine whether Pakistan uses the Reko Diq copper and gold project as a turning point or repeats the long pattern of wasted opportunities. The future can unfold in two very different ways.

Scenario A: Pakistan Reforms and Reko Diq Delivers

If Pakistan builds stable institutions, develops downstream industries and ensures fair revenue sharing, Reko Diq can become a foundation for national stability. Export earnings will strengthen the external account, Balochistan will experience real development and Pakistan’s industrial base will expand. The project will also enhance Pakistan’s strategic importance in global supply chains during a period of rising copper demand.

Scenario B: Pakistan Repeats Past Mistakes

If governance remains weak and downstream strategy is ignored, Pakistan will earn only limited royalties while foreign partners capture most of the value. Local communities will stay deprived, tensions may rise and the economic benefits will fall short of expectations. The country will miss a historic opportunity and remain dependent on IMF programmes. Reko Diq will become another example of how Pakistan mines its potential but not its prosperity.

“Pakistan’s future is not decided by geology. It is decided by governance, planning and political will. The difference between prosperity and stagnation lies in the choices made today.”

CONCLUSION

Reko Diq is more than a mining site. It is a mirror reflecting Pakistan’s strengths and weaknesses. The country owns a world-class deposit, yet decades of mismanagement, political instability and institutional fragility kept it undeveloped. The lost time cost Pakistan billions in potential exports, employment and industrial growth. But the story is not over. If Pakistan chooses reform, Reko Diq can still become a catalyst for long-term transformation. Strong institutions, fair revenue sharing and downstream industries can convert this resource into real national strength.

CALL TO ACTION

Pakistan must choose a clear direction. The Reko Diq copper and gold project should become a national priority backed by predictable laws, transparent revenue systems and modern industrial planning. If Pakistan commits to this pathway, mineral wealth can be turned into sustainable development. If it delays again, the opportunity will fade and the country will remain stuck in the cycle of external dependence.

5 thoughts on “Reko Diq Copper–Gold Project: Wealth Potential, Governance Gaps & Pakistan’s Resource Paradox”

Excellent

Worth it👍

Great job Sir 👏👏

Marvelous 👍

Nice info btw!