Indo-Pacific blue economy, blue economy geopolitics, Indo-Pacific maritime economy, maritime trade routes, Indian Ocean economics, South China Sea trade risks, blue finance Asia, fisheries economics, undersea cables, ocean governance ASEAN

Introduction: The Indo-Pacific Blue Economy Emerges

The Indo-Pacific blue economy marks a decisive shift in global economic power. Oceans are no longer peripheral to growth. Instead, they anchor trade flows, food systems, energy security, digital connectivity, and geopolitical influence.

Stretching from the Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific, the region carries nearly 60 percent of global trade and supports over 120 million ocean-dependent livelihoods. Recent maritime disruptions have shown how instability at sea transmits inflation and supply shocks worldwide, as seen during https://economiclens.org/red-sea-turmoil-suez-canal-disruptions-and-the-global-shipping-shock/ which exposed the fragility of global shipping networks.

1. Indo-Pacific Blue Economy and Strategic Sea Lanes

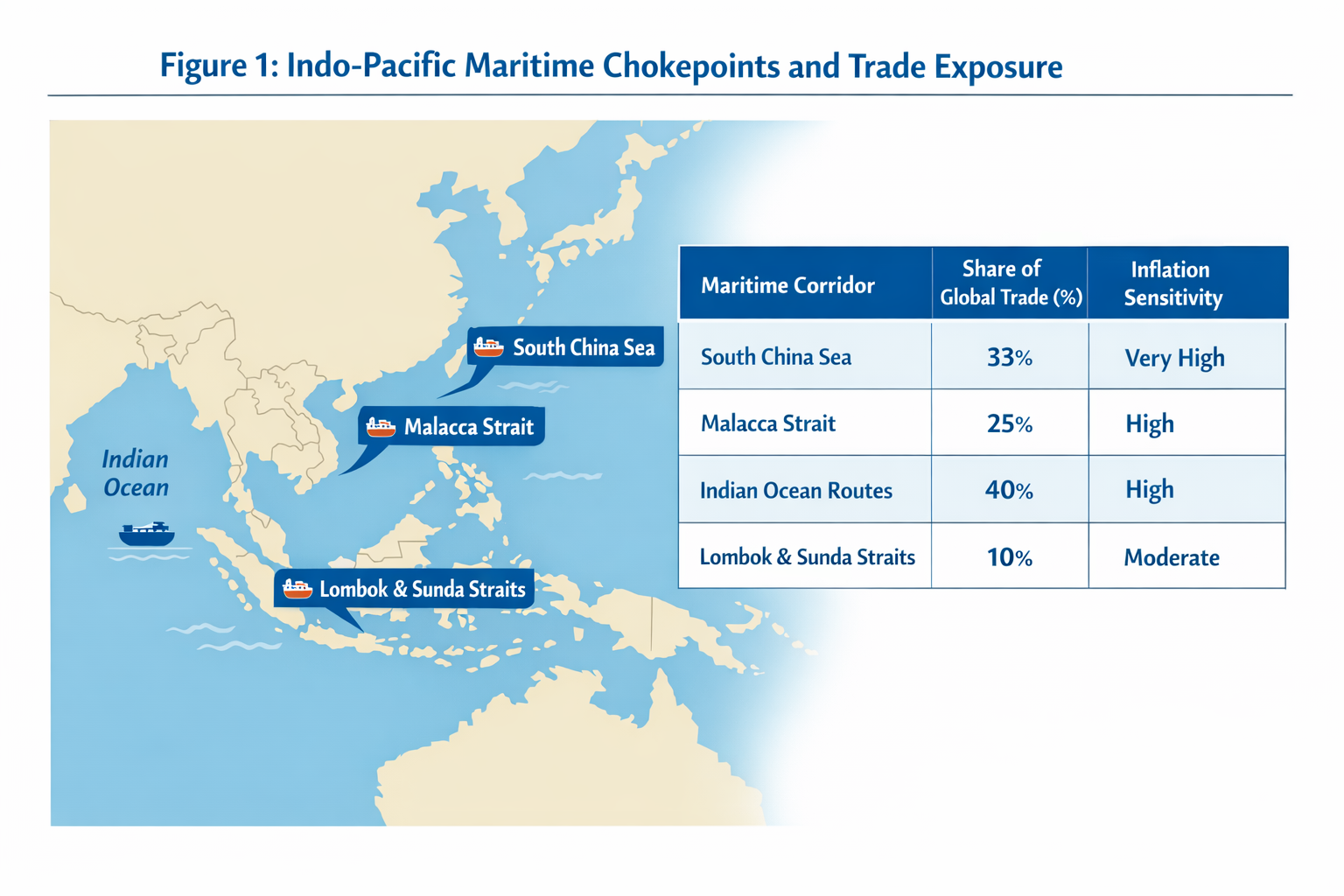

Sea lanes sit at the core of the Indo-Pacific blue economy. Energy shipments, manufactured goods, and food commodities move through a limited number of highly concentrated corridors. Consequently, even localized disruptions now generate global inflationary pressure.

Global Expert and Report Signals

The World Bank (https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects) and UNCTAD (https://unctad.org/publication/review-maritime-transport) identify Indo-Pacific maritime chokepoints as systemic risk nodes rather than logistical bottlenecks. Recent assessments show that insurance premiums, freight rates, and delivery times now respond immediately to geopolitical tension, embedding maritime risk directly into global price dynamics.

This figure shows how global trade is structurally concentrated in Indo-Pacific sea lanes. Because commerce flows through so few corridors, short disruptions transmit cost shocks through freight rates, insurance premiums, and consumer prices worldwide.

Strategic Sea Lanes and Blue Economy Geopolitics

During 2024 and 2025, heightened naval activity and overlapping claims increased uncertainty across key Indo-Pacific corridors. Shipping firms rerouted vessels to reduce exposure, lengthening voyages and raising fuel costs. Insurers revised risk models, while exporters faced delays and higher logistics expenses, reinforcing inflationary pressure across importing economies, a trend highlighted in UNCTAD shipping risk reviews at https://unctad.org/topic/transport-and-trade-logistics.

“When sea lanes destabilize, inflation accelerates globally, supply chains fracture rapidly, and maritime chokepoints expose how ocean stability now anchors price control.”

2. Indo-Pacific Maritime Economy and Port Infrastructure Rivalry

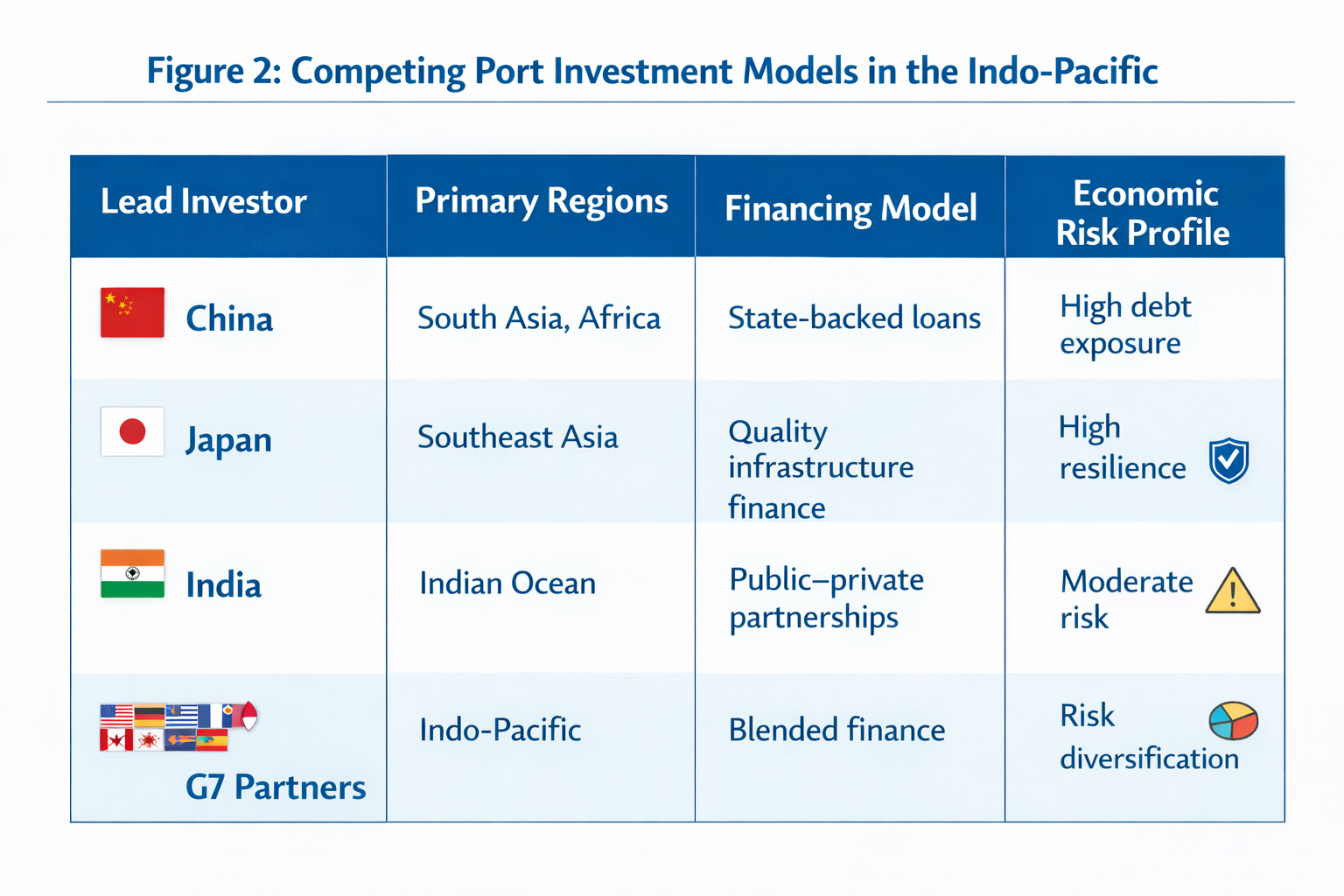

Ports have become strategic assets within the Indo-Pacific maritime economy, shaping trade flows, investment patterns, and supply-chain resilience. Beyond cargo handling, port ownership and control increasingly influence how economies align with regional trade networks and external financiers.

Financing models now play a decisive role in this rivalry. State-backed loans, public–private partnerships, and multilateral financing differ sharply in their fiscal implications. Highly leveraged port projects can raise long-term debt exposure, while diversified or blended financing tends to improve flexibility during trade disruptions and demand shocks.

Operational control further defines competitive outcomes. Ports with transparent governance and diversified operators usually adjust faster to congestion, price volatility, and route realignments. By contrast, ports dependent on single operators or financiers face tighter constraints during crises. As a result, port competition in the Indo-Pacific is no longer only about throughput, but about economic resilience and strategic autonomy.

Global Expert and Report Signals

OECD and World Bank port performance studies show that economies reliant on single-creditor port financing face significantly higher vulnerability to external shocks, including geopolitical tensions, shipping disruptions, and sudden rerouting of trade flows, as highlighted in OECD research on port governance and infrastructure resilience (https://www.oecd.org/transport/ports/). This OECD port and infrastructure resilience research finds that concentration of financing increases exposure to debt stress, refinancing risk, and political leverage during periods of global instability.

Similarly, World Bank port sector and logistics performance assessments indicate that ports backed by diversified financing models, including multilateral development banks, private investors, and public–private partnerships, demonstrate stronger operational continuity and faster recovery during trade disruptions, according to the World Bank’s ports and waterways analysis (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/transport/brief/ports-and-waterways) and its Logistics Performance Index evaluations (https://lpi.worldbank.org/). These diversified structures reduce fiscal pressure on host economies and improve resilience when maritime routes are disrupted or redirected.

This table highlights that port investment is not neutral. Financing structures determine whether host economies build long-term resilience or inherit fiscal vulnerability during trade shocks.

Port Competition in the Indo-Pacific Maritime Economy

As global shipping patterns shifted, Southeast Asian ports experienced severe congestion. Container dwell times increased, exporters faced shipment delays, and logistics costs surged. Governments accelerated expansion plans, yet capacity gaps and regulatory delays limited rapid response, reinforcing findings from OECD transport competitiveness reviews at https://www.oecd.org/transport/.

“Ports now shape economic destiny by transmitting shocks, locking trade dependence, and deciding which economies absorb crises or preserve resilience.”

3. Indo-Pacific Blue Economy, Fisheries, and Food Security

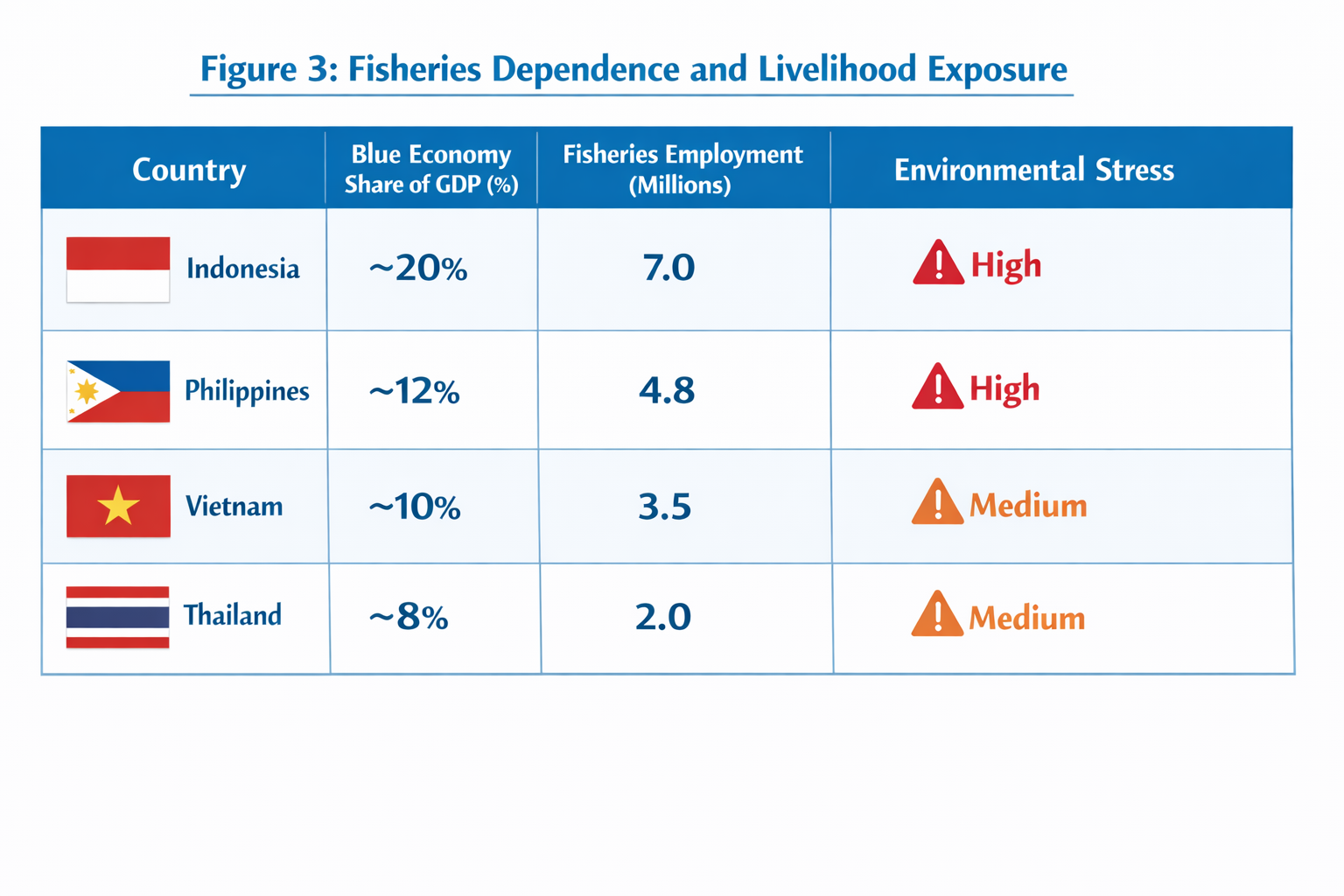

Fisheries are the human backbone of the Indo-Pacific blue economy, supporting millions of livelihoods and providing a critical source of affordable nutrition across coastal and island economies. Small-scale fishing sustains employment, underpins local food systems, and plays a stabilizing role in rural and informal labor markets.

This foundation is increasingly under strain. Overfishing, illegal fishing, and climate-driven ecosystem change are reducing fish stocks and disrupting traditional fishing zones. Rising ocean temperatures and acidification are pushing species migration, raising costs for fishers and weakening income stability. These pressures are already translating into higher food prices and greater import dependence in many Indo-Pacific economies.

As fisheries decline, economic vulnerability and resource competition intensify. Safeguarding marine resources is therefore not only an environmental concern. It is essential for food security, employment resilience, and long-term economic stability across the Indo-Pacific region.

Global Expert and Report Signals

FAO and UNEP reports show accelerating fish stock depletion, coral reef loss, and mangrove degradation across Southeast Asia, undermining the ecological base of the Indo-Pacific blue economy (FAO: https://www.fao.org/state-of-world-fisheries-aquacultureUNEP: https://www.unep.org/resources/report

This table links economic reliance on marine sectors with exposure to environmental stress. Countries with higher dependence face greater risks to food security, employment stability, and rural livelihoods.

Fisheries Stress and Coastal Livelihood Loss

Across Southeast Asia, declining fish stocks, increasingly erratic weather, and rising fuel costs have sharply reduced daily catches and raised operating risks for coastal fisheries. Small-scale fishers report falling and unstable incomes, alongside limited access to credit, insurance, or formal safety nets. As livelihoods weaken, migration from coastal communities has accelerated, pushing displaced workers toward already strained urban labor markets and informal employment. This emerging pattern of fisheries-linked economic displacement is documented in recent FAO regional fisheries outlooks (https://www.fao.org/home/en), which highlight the growing connection between marine stress, income insecurity, and internal migration pressures.

“As marine ecosystems decline, incomes shrink, food insecurity spreads, and coastal inequality intensifies, converting environmental damage into systemic economic risk.”

4. Ocean-Based Economic Rivalry and the Blue Finance Gap

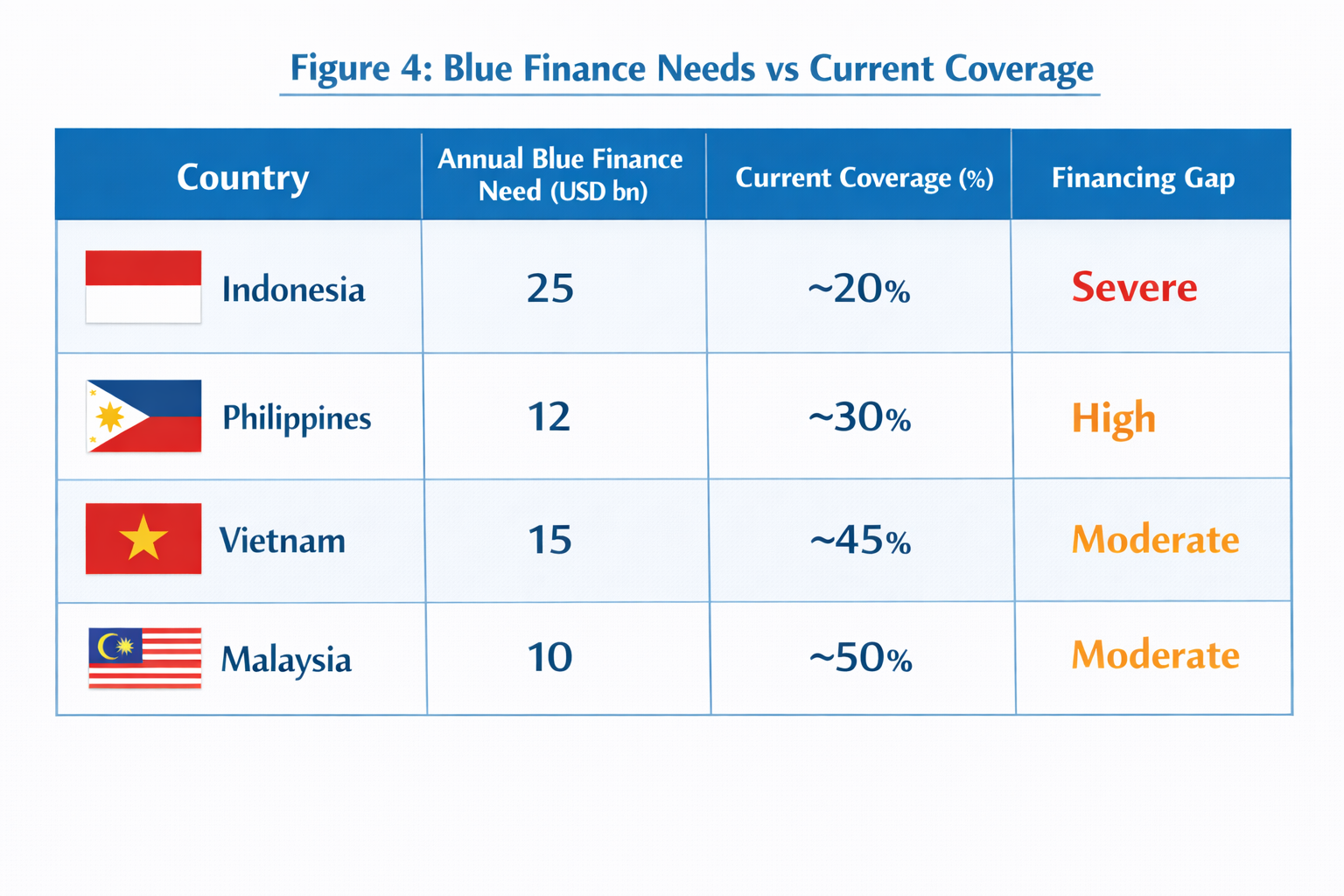

The Indo-Pacific blue economy has the potential to generate more than 500 billion USD annually by 2030, driven by maritime trade, fisheries, coastal tourism, offshore energy, and marine biotechnology. This growth potential has elevated oceans from a peripheral environmental concern to a central arena of economic and strategic competition among regional and global powers.

Despite this scale, blue economy financing remains uneven and poorly aligned with ecological outcomes. Investment continues to concentrate in ports, shipping infrastructure, and extractive activities, while sustainable fisheries, coastal resilience, and marine conservation receive a disproportionately small share of capital. Public funding is often fragmented, and private investors face weak regulatory clarity, limited risk-sharing mechanisms, and inconsistent project pipelines.

The result is a widening blue finance gap. Economies with strong balance sheets and access to global capital markets are expanding ocean-based assets rapidly, while developing coastal states struggle to fund climate adaptation, ecosystem protection, and livelihood diversification. Without coordinated standards, blended finance instruments, and multilateral support, ocean-based growth risks intensifying inequality, environmental degradation, and geopolitical rivalry rather than delivering shared and sustainable prosperity across the Indo-Pacific.

Global Expert and Report Signals

IMF and Asian Development Bank analyses highlight a persistent gap between the rapid growth of blue finance instruments and measurable environmental recovery, raising concerns about impact effectiveness (IMF: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications, ADB: https://www.adb.org/what-we-do/sectors/transport). This mismatch increases long-term fiscal exposure, as insufficient ecological restoration amplifies climate-related disaster losses, raises reconstruction costs, and places sustained pressure on public budgets.

This chart reveals a structural mismatch between financing needs and actual investment. Underfunding today raises future fiscal liabilities through ecosystem collapse and income instability.

The Blue Finance Paradox in Emerging Asia

Several Indo-Pacific economies have expanded sustainability-labeled borrowing for ocean-related projects, yet progress in ecosystem restoration and community-level adaptation has lagged behind capital inflows. As climate risks intensify, disaster recovery and reconstruction costs continue to rise, reinforcing IMF warnings on climate finance and fiscal vulnerability (https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change).

“Sustainability finance without resilience outcomes delays crisis resolution, inflates future fiscal costs, and leaves ecosystems and livelihoods increasingly exposed.”

5. Digital Oceans and the Future of the Indo-Pacific Blue Economy

The Indo-Pacific blue economy increasingly depends on digital infrastructure that underpins modern maritime activity. Undersea fiber-optic cables, satellite networks, and data platforms now play a central role in ensuring trade continuity, monitoring vessel movements, and supporting port and logistics operations across the region. These systems have become as strategically important as physical sea lanes.

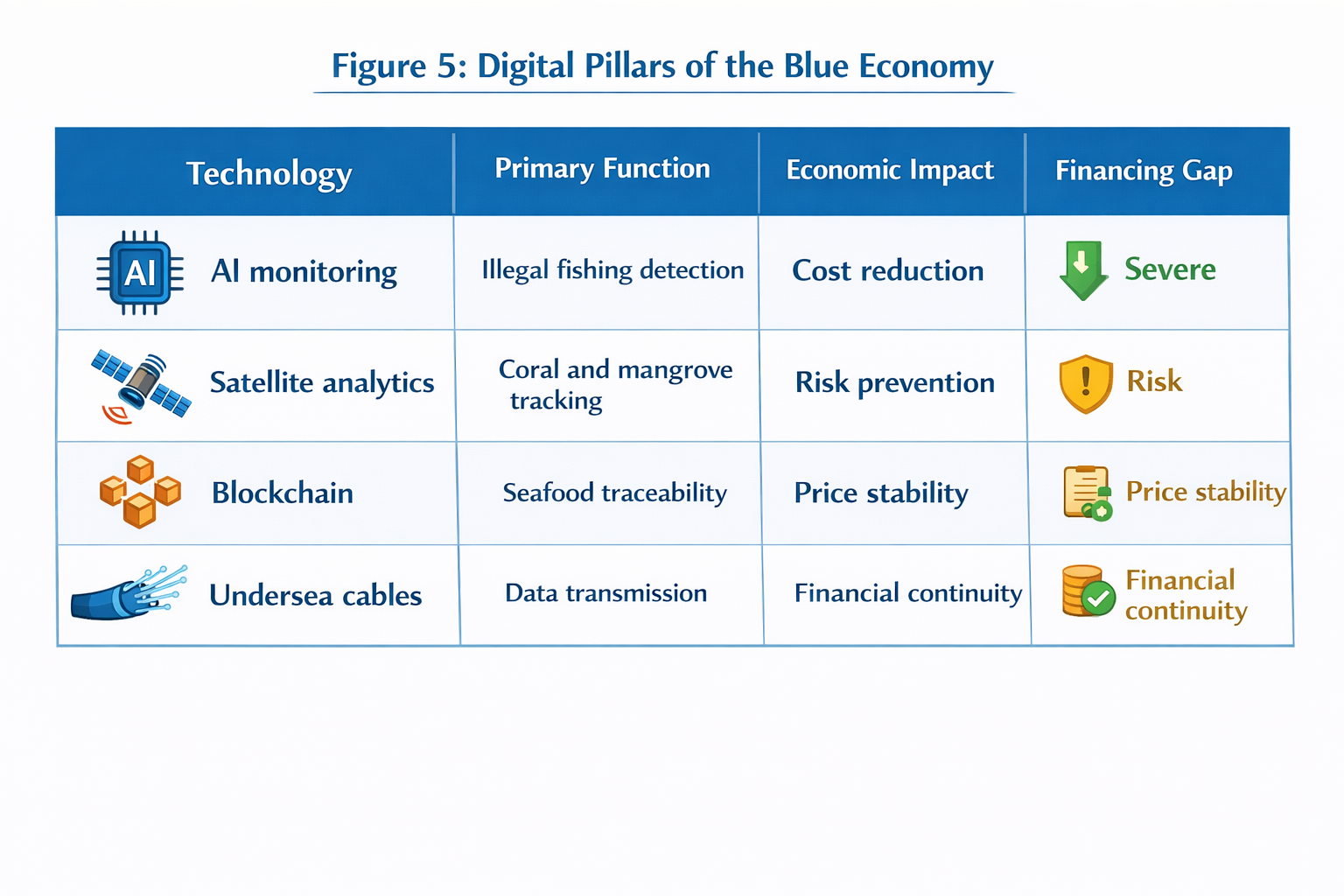

Digital technologies are also transforming maritime governance and enforcement capacity. Satellite-based tracking, AI-powered analytics, and automated identification systems enable authorities to detect illegal fishing, monitor environmental compliance, and improve safety at sea. When effectively deployed, these tools enhance transparency, reduce revenue leakage, and strengthen regulatory oversight in complex and contested maritime spaces.

However, reliance on digital oceans introduces new vulnerabilities. Undersea cables and satellite systems are exposed to geopolitical risk, cyber threats, and physical disruption. Uneven access to digital infrastructure also risks widening gaps between advanced maritime economies and developing coastal states. Securing and democratizing digital maritime systems will therefore be critical to ensuring that the Indo-Pacific blue economy remains resilient, transparent, and inclusive in the decades ahead.

Global Expert and Report Signals

World Bank and OECD research identifies digital ocean systems, including undersea cables, satellite networks, and maritime data platforms, as critical economic infrastructure (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/digitaldevelopment, https://www.oecd.org/digital/). Disruptions to these data flows can simultaneously halt payments, trade coordination, and maritime monitoring, transforming localized technical failures into systemic economic risk.

This figure shows that digital systems now underpin ocean governance. Control over data flows increasingly shapes economic resilience and strategic power.

Digital Competition in the Indo-Pacific Blue Economy

Governments accelerated investments in satellite surveillance, AI enforcement, and undersea cable protection. Concerns over data sovereignty and technology dependence intensified, prompting debates over shared governance frameworks, as highlighted in World Bank ocean governance studies at https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/oceans.

“In the blue economy, control of data flows, digital monitoring, and undersea infrastructure increasingly determines power, resilience, and economic continuity.”

Conclusion: The Indo-Pacific Blue Economy as the New Economic Frontier

The Indo-Pacific blue economy reflects a structural transformation in global economics. Oceans now host trade, food systems, finance, digital infrastructure, and geopolitical rivalry within the same space.

Without coordinated governance, ecological loss and inequality will deepen. With aligned finance, technology, and regional cooperation, the Indo-Pacific’s oceans can instead anchor sustainable growth and long-term stability.

Final Call to Action

Treating oceans as expendable infrastructure will magnify fiscal exposure, food insecurity, and livelihood losses. Treating them as strategic economic assets can anchor sustainable trade, protect coastal economies, and stabilize global price dynamics.