Explore how the Indo-Pacific’s blue economy is driving sustainable development—advancing ocean innovation, marine conservation, and climate-resilient growth for a sustainable future

A Region at the Crossroads

The Indo-Pacific is approaching a new era in which seas serve not only as natural lifelines but also as economic battlegrounds. This marine stretch, extending from the Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific, facilitates approximately 60 percent of world commerce and supports the livelihoods of over 120 million people (FAO, 2025). However, it confronts increasing challenges from overfishing, coral bleaching, and pollution.

Indonesia, the preeminent archipelagic country globally, underpins this transformation. The nation, with 17,000 islands and a marine sector that accounts for approximately 20 percent of GDP, exemplifies both the potential and risks of the regional blue economy (BPS, 2024; World Bank, 2025). If managed sustainably, the waters of the Indo-Pacific might generate over 500 billion USD in annual economic value by 2030 (ASEAN Blue Finance Review, 2025). However, in the absence of synchronized investment and governance, they are susceptible to ecological degradation and geopolitical stress. According to UNEP (2024), the blue economy’s potential is limitless only if financial resources are directed towards sustainable initiatives.

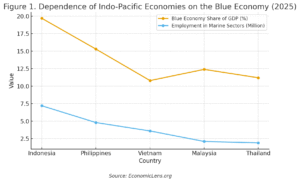

The Dependence of Indo-Pacific Economies on the Blue Economy

The economic framework of the Indo-Pacific is intrinsically reliant on the water. The blue economy significantly contributes to GDP, employment, exports, and food security in Southeast Asia. Over 70 percent of the population resides in coastal areas, with millions relying on fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism for their livelihoods (FAO, 2025; World Bank, 2025).

These statistics illustrate the ocean’s pivotal role in regional wealth. Indonesia’s blue economy constitutes around one-fifth of its GDP and provides employment for over seven million people, making marine resources a cornerstone of national stability (BPS, 2024). In the Philippines, fishing and aquaculture support 4.8 million jobs and facilitate rural development. Vietnam, however less dependent in relative terms, has emerged as a worldwide aquaculture center, exporting over fifty percent of its marine goods to international markets (FAO, 2025).

Malaysia and Thailand have a distinct pattern of reliance: service-oriented economies driven by tourism, shipping, and seafood exports. Collectively, these industries account for more than 20 percent of the export revenues of both countries (OECD, 2025). Nonetheless, their environmental susceptibility is similarly pronounced—coastal erosion, plastic pollution, and coral bleaching jeopardize the long-term sustainability of these businesses (UNEP, 2024).

This data highlights a fundamental truth: economic stability and ocean health are intrinsically linked. A deterioration in marine ecosystems immediately results in diminished revenue, decreased employment, and sluggish GDP growth. In contrast, the sustainable management of marine resources may provide an estimated extra annual value of 500 billion USD by 2030 (World Bank, 2025).

The Anatomy of a Blue Economy Reformation

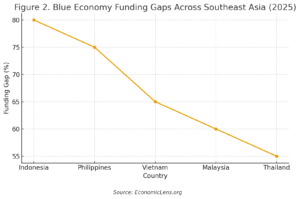

The blue economy aims to harmonize economic expansion with environmental conservation—a need in a region where marine degradation incurs a projected yearly cost of three percent of GDP (OECD, 2025). Throughout Southeast Asia, governments are implementing blue development policies; yet, the data shown below underscores a recurring issue: insufficient finances continue to hampers the progress.

The data indicate a persistent correlation between environmental stress and inadequate funding. Indonesia requires around 25 billion USD yearly for blue development but fulfills just about one-fifth of that goal. The Philippines and Vietnam have such deficiencies, when economic deficits adversely impact environmental and societal resilience.

This trend highlights the interdependence between financial inclusion and ecological stability. In nations with greater financing deficits, like Indonesia and the Philippines, the degradation of coral reefs, the depletion of mangroves, and overfishing are more rigorous. Conversely, Malaysia and Thailand, albeit being underfunded, have superior environmental performance attributed to enhanced investment in research and development and focused marine conservation efforts (Asian Development Bank, 2025).

Bridging the blue finance gap requires not just more capital but also improved allocation. The majority of financing mostly supports large-scale infrastructure initiatives, such as ports and shipping decarbonization, resulting in inadequate resources for smaller community-based adaption programs (World Bank, 2025). To convert the blue economy from policy vision to tangible effect, governments must establish funding channels that extend to the local level—where environmental degradation is most severe and adaptation is most critical.

From Exploitation to Resilience: Environmental & Financial Trends

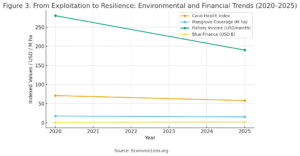

The marine ecosystems of the Indo-Pacific are under mounting pressure. The following indicators demonstrate the increasing ecological deterioration and economic instability seen over the previous five years.

Despite a more than 200 percent increase in blue finance distribution since 2020, environmental and social results persist in their decline. The health of coral reefs has diminished by 18 percent, while mangrove coverage has decreased by 13 percent. These losses immediately compromise coastal protection and biodiversity, increasing susceptibility to harsh weather and erosion (UNEP, 2024).

Concurrently, the average income of small-scale fishermen has decreased by about one-third, from 280 to 190 USD per month (FAO, 2025). This decline underscores the connection between ecological deterioration and human insecurity, especially for populations reliant on the sea for food and economic stability. The data indicate that while blue finance is growing, its effects remain inconsistent.

Numerous financial instruments, such as blue bonds, have financed substantial infrastructure or renewable energy initiatives, with no direct assistance for ecological restoration or community-based adaptation (IMF, 2025). The area confronts what the IMF designates as the “blue debt paradox”—nations borrow in the name of sustainability but remain trapped in cycles of environmental degradation.

To counteract these tendencies, funding must be linked to quantifiable biological metrics—such as coral regeneration, fish population recovery, or mangrove reforestation—rather than broad spending classifications. Genuine resilience will manifest only when economic advancement and environmental well-being progress together.

Tracking the Pulse of the Blue Economy

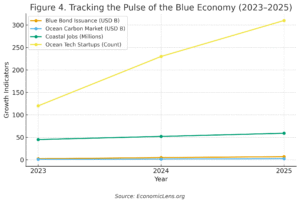

Despite concerns about ecological deterioration, the economic indicators of the Indo-Pacific demonstrate a rapid increase in ocean-based development, finance, and innovation.

This data illustrates the rapid emergence of the blue economy as a cornerstone of regional development. The total issuance of blue bonds has quadrupled over three years, indicating a growing investor trust in sustainable maritime assets. Concurrently, the regional ocean carbon market has seen a twofold increase in value, propelled by corporate demand for blue carbon credits produced by mangrove and seagrass restoration (UNDP, 2025).

The increase in coastal employment—from 45 to 59 million jobs—demonstrates that the blue economy is progressively a catalyst for equitable growth. Job creation include aquaculture, eco-tourism, and coastal infrastructure (FAO, 2025). The increase in ocean technology firms, from 120 in 2023 to over 300 in 2025, highlights the expanding convergence of data, innovation, and marine sustainability (OECD, 2025).

Nonetheless, the fundamental problem persists in converting these development tendencies into real environmental restoration. The expansion of markets and the introduction of new capital instruments should lead to enhanced reef health, restored biodiversity, and stable livelihoods. In the absence of fundamental connection, economic growth threatens to obscure underlying ecological vulnerability. The future of the blue economy will be assessed not by the financial investments made, but by the concrete restoration it provides to marine ecosystems and the communities reliant on them.

Innovation Currents: Climate Tech and the Future of Ocean Intelligence

The blue economy of the Indo-Pacific cannot achieve its potential just via finance; it requires technology as its driving catalyst. Digital innovation, ranging from predictive climate analytics to autonomous marine drones, is transforming the management of marine resources and the monitoring of sustainability results by governments.

AI-driven tools now predict coral bleaching six months ahead, allowing Indonesia and the Philippines to prioritize reef restoration areas (UN-SPIDER, 2025). Marine robots are mapping seagrass and coral ecosystem more effectively than conventional field surveys, while blockchain traceability guarantees openness across seafood supply chains (OECD, 2025).

Simultaneously, entrepreneurs in Singapore and Jakarta are innovating in ocean carbon capture via kelp farming and deep-sea biomass sequestration (UNEP, 2024). Collectively, these activities have the potential to establish a 40 billion USD maritime technology industry in the Indo-Pacific by 2030 (World Bank, 2025).

According to FAO (2025), the efficacy of the blue economy relies equally on data and technology as it does on financial resources. The developing “digital ocean” will need cohesive systems that amalgamate real-time data, AI analytics, and communal expertise to promote fair and sustainable governance.

The Digital and Financial Backbone of Blue Growth

Technology and money today constitute the dual catalysts of maritime resilience. Launched in 2024, Indonesia’s Ocean Data Platform amalgamates satellite surveillance with artificial intelligence to identify unlawful fishing and coral bleaching in real time (UN-SPIDER, 2025). In the Philippines, blockchain technologies enable small-scale fishermen to track and authenticate sustainable harvests, enhancing market access and price stability.

Simultaneously, innovative financial mechanisms are proliferating: Indonesia’s 1.5 billion USD sovereign blue bond has funded coral restoration and low-carbon ports, while Malaysia and the Philippines are investigating debt-for-nature swaps that reallocate loan repayments to conservation funds (Asian Development Bank, 2025). Vietnam’s experimental resilience-linked loans associate interest rates with enhancements in biodiversity—a paradigm that may transform global sustainable finance (IMF, 2025).

This trend indicates the emergence of what researchers term “ecological capitalism,” whereby natural resources provide quantifiable commercial worth. Nonetheless, in the absence of transparency and regulation, even sustainable capital may perpetuate unfairness. Enhancing institutional capacity to oversee these flows is crucial for ensuring accountability and equitable results.

Geo-Economics of the Ocean Frontier

In the Indo-Pacific, maritime policy and geopolitics have grown intertwined. The ocean has become a platform for strategic rivalry and regional diplomacy. Indonesia’s Archipelagic Outlook is congruent with Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific and India’s Sagarmala Initiative, highlighting sustainability and marine connectivity (UNDP, 2025).

Simultaneously, China’s Maritime Silk Road investments have proliferated, financing ports and coastal infrastructure while eliciting apprehensions over debt sustainability and environmental hazards (IMF, 2025). To harmonize these dynamics, ASEAN and development partners, including the Asian Development Bank, are advocating for collaborative frameworks such as the ASEAN Blue Economy Roadmap and ADB’s Blue Finance Facility (Asian Development Bank, 2025).

The UNDP (2025) notes that the future of the Indo-Pacific would be shaped not by terrestrial boundaries but by the collective management of its maritime domains.

Human Impact: The Social Tide

The blue economy is fundamentally a human tale. In the area, women, youth, and small-scale fishermen disproportionately suffer from environmental degradation. In Indonesia, three million women are employed in fisheries but do not have access to finance or insurance (FAO, 2025). Increasing sea levels jeopardize towns in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta and the Philippines’ Visayas, exacerbating inequality and migration challenges.

Sustainable ocean management must be fundamentally based on social inclusion. Gender justice, community education, and microfinance are essential precondition for resilience. In its absence, the blue economy is likely to reproduce the same disparities that have historically influenced terrestrial growth.

The Road Ahead

By 2030, the blue economy of the Indo-Pacific may become the globe’s most rapidly expanding sustainability market. Attaining that objective requires a coordinated strategy across countries and sectors.

⦁ Establish blue financing allocations according to ecological performance indicators.

⦁ Designate a minimum of fifty percent of all marine funding for adaptation and community-driven restoration efforts.

⦁ Implement AI monitoring systems for immediate transparency and accountability.

⦁ Enhance transnational governance via ASEAN-led frameworks.

⦁ Leverage private capital using blended finance and ESG-linked investment incentives.

If executed proficiently, these steps may transform the Indo-Pacific’s seas from a victim of expansion into a cornerstone for regional resilience and prosperity.

Policy Implications

Three prominent policy strategies are: incorporating marine sustainability into budgetary planning, enhancing regional governance, and guaranteeing localized effect.

First, the ministries of finance and environment must integrate blue financing into national budgets and long-term economic goals (World Bank, 2025). Secondly, regional organizations like ASEAN and ADB must to unify data and accountability frameworks to enhance transparency and ensure fair access to financing (OECD, 2025). Ultimately, ocean finance should emphasize local involvement, guaranteeing that small-scale fishermen, women, and community entrepreneurs are primary beneficiaries rather than marginal participants (FAO, 2025).

Collectively, these measures may convert blue money from a top-down program into a grassroots mechanism for sustainable development.

Final Word

The blue frontier of the Indo-Pacific signifies the next stage of world economic evolution. Indonesia’s leadership in blue finance provides a regional model: invest in nature, digitize government, and democratize opportunities. In the next decades, countries that safeguard their seas will not only withstand the climatic catastrophe but will also spearhead the next era of prosperity. As the OECD (2025) notes that the struggle for economic significance in the twenty-first century will occur on the world’s oceans.

The choice before the region is clear: “treat the ocean as expendable infrastructure or as the strategic asset that secures prosperity, stability, and dignity for generations to come”.

Researcher’s Insights

The Indo-Pacific’s blue transformation is developing into a dynamic laboratory for sustainable finance and governance. Principal research priorities encompass:

⦁ Assessing resilience returns—evaluating the macroeconomic advantages of ocean investment (World Bank, 2025).

⦁ Debt-for-resilience modeling—analyzing the potential of sovereign debt swaps to stabilize public finances while fulfilling conservation objectives (IMF, 2025).

⦁ Digital ocean governance—evaluating the contributions of AI and blockchain to transparency (UN-SPIDER, 2025).

⦁ Inclusive blue finance—assessing equal access for women and small companies (FAO, 2025).

⦁ Regional coordination—assessing ASEAN’s capacity to standardize blue economy regulations (OECD, 2025).

Oceans can foster equitable development only if equality serves as their driving principle.